When colleagues in the Department of Communication review the creative achievements listed on my vita, they often inquire, “What is a dramaturg?” Since the nature of my dramaturgy changes depending on the type of work I’m involved in as a theatre practitioner, it’s not an easy question to answer [2]. Once when this question came to my desk in an email message, I sent my colleague a couple of website addresses that provide exhaustive listings of a dramaturg’s tasks. Another time, the question was posed in the hallway when I was in the middle of rehearsals for a new play. That time, I gave a rather standard response:

A dramaturg serves multiple roles. Before or during rehearsals, a dramaturg reads and assesses the play-in-development; typically serves as a liaison between the playwright and the director; serves also as a resource for performers, designers, and technical crew; and, prior to the opening of show, writes up his or her notes for the program. During the course of a new play’s run, a dramaturg’s job continues as the dramaturg is there to keep and eye on the story, to ensure the director’s and playwright’s production goals remain solidly in focus.

And because the majority of my colleagues in the Department of Communication most likely would not be interested in any further explication of how dramaturgy works for original plays, I would spare them my enthusiasm about the recent scholarship on dramaturgy as it relates to “community-based theatre,” “non-realism” and “collaborative creation” –all genres or methods in which I have and continue to work. (Haedicke, Harding-Smith, and Lynn and Sides.)

Dramaturgy has always fascinated me. Eight years ago, in a short essay in the Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism, Gayle Austin posed a number of provocative questions, three of which I find particularly relevant to my artistic career:

What comes to mind when you see the phrase, “Feminism and Dramaturgy”?

What is, or would be, a feminist methodology of doing dramaturgy?

What if any, is the relationship between the dramaturg and the idea of a “female aesthetic” in playwrighting? In directing? (122-123) [3]

What is, or would be, a feminist methodology of doing dramaturgy?

What if any, is the relationship between the dramaturg and the idea of a “female aesthetic” in playwrighting? In directing? (122-123) [3]

When Gayle Austin was asking those three questions in l998, I was, although I was not aware of it, smack dab in the middle of answering them for myself, not academically or theoretically, but in practice. So, it is only now, after having spent two decades of my life creating political theatre with my partner Terry Galloway, and, more specifically, after having analyzed my extensive field notes on the development of one particular feminist show, Lardo Weeping—that I find myself ready to enter into the conversation.

I shall begin by providing a brief description of Lardo Weeping—a seventy-minute, solo performance piece, written and performed by Terry Galloway. Then I will chronologically review the production history of Lardo Weeping, supplying detailed examples in order to aptly, amply and effectively demonstrate three larger points I want to make about “feminism and dramaturgy.”

• First, feminist dramaturgs should contemplate, and whenever possible document, the ways that the feminist community at large (its theorists, students, technicians, artists, spectators) serve as invisible dramaturgs for feminist productions.

• Second, feminist dramaturgs should not buy into the premise that dramaturgy stops when the curtains have closed. More longitudinal studies are needed on feminist dramaturgy as it relates to staged readings, workshop performances and productions—in other words dramaturgy as it relates to the development of feminist playwrights’ text, particularly in connection with changing historical and cultural circumstances.

• Third, feminist dramaturgs should consider following Erik Ehn’s advice: “The best thing a dramaturg can do is to co-create, to create a conundrum as problematic as the play itself.” (qtd. in D.J. Hopkins, 4).

Lardo Weeping and Its Dramaturgical Documentation

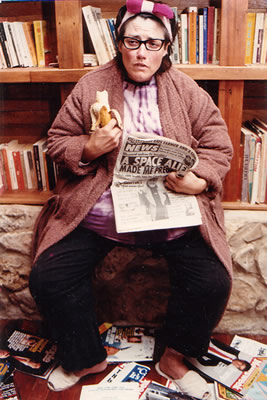

Lardo Weeping features a day in the life of Dinah LaFarge—a large, outspoken, unemployed, middle-aged, intellectual agoraphobe. Dinah LaFarge is a postmodern heroine, a character who knows her essential self is a fiction yet still believes in herself willingly. In an early essay I published on the show, I demonstrate the myriad ways that Lardo Weeping affirms the existence of Dinah LaFarge’s individual identity (her marginalized voice); dramatizes her multiple, fragmented and socially-constituted identities; and underscores the complex and often concurrent identities of Dinah LaFarge and her creator, Terry Galloway. I argue that Lardo Weeping works to successfully bridge and challenge liberal feminist and postmodern feminist views of identity (Nudd, “Postmodern”).

This earlier essay touches upon my creative partnership with Galloway, demonstrating how we worked together to shape Lardo Weeping, Galloway as writer and performer, I as dramaturg and director. This essay in Liminalities seeks to explore another creative partnership that was formed to create Lardo Weeping—the one we entered into with the feminist community. Thus, while my earlier essay foregrounds the artists’ final product, this essay foregrounds feminists’ influence on the process, particularly how feedback from the feminist community directly or indirectly contributed to the development of Lardo Weeping. In documenting the insights from feminists during the show’s almost twenty-year production history, I argue that feminists—be they theorists, students in my classes, technical crew, spectators or readers of the written text—served as invisible dramaturgs who helped turn Dinah LaFarge into a postmodern heroine.

In this essay, I shall trace, chronologically, moments in the development of Lardo Weeping where feedback from a feminist—be it a comment, a telephone conversation, an insight from a theoretical book, a wise crack, a journal article, a heated argument, a classroom insight, a fax—significantly challenged the way that Galloway and I envisioned Dinah LaFarge. Two lengthy journals—in which I entered reactions, comments, and ideas concerning the show, sometimes directly after each production, other times during the speculative months between productions—greatly aided me in reviewing and analyzing the show’s dramaturgical process (Nudd, “Notes”) (Nudd, “2002 Austin”). If Galloway and I succeeded in bridging and challenging the liberal feminist and postmodern feminist views of identity, which is what my earlier article claims, then we did so primarily because we listened carefully to other feminists. More specifically we used their critical insights to help us pinpoint and solve problematic aspects of the character’s identity.

Thus, this essay focuses narrowly on the ways that feminists continually and constantly questioned, affirmed or challenged Galloway’s and my conception of what it means to put a poor, obese, intellectual, white, liberal woman on stage in America at the turn of the century [4]. Or in other words, this paper examines the complex ways that feminist spectators helped construct and situate Dinah LaFarge as a postmodern heroine [5].

The Birth of a Character, l987-88 [6]

The Department of English at Florida State University sponsors a once-a-week poetry night at a local pub where writers from the university or from the community read new work. In the fall of l987, Terry Galloway was asked to do a reading. Days before her scheduled reading, Galloway sat down at her computer and wrote four or five new poems and then proceeded to integrate them with some chitchat and comic characterizations. Her half hour reading was well received. Weeks later the artistic director of a theatre in Austin, Texas called and requested that Galloway come in January to Texas to perform. Since Galloway had performed her solo show, Out All Night and Lost My Shoes, a number of times in Austin previously, her Florida friends, myself included, urged her to create something new. Feeling a bit bullied by her friends, Galloway returned to her FSU poetry presentation on her computer disc and began the process of reshaping it into a performance piece.

The Department of English at Florida State University sponsors a once-a-week poetry night at a local pub where writers from the university or from the community read new work. In the fall of l987, Terry Galloway was asked to do a reading. Days before her scheduled reading, Galloway sat down at her computer and wrote four or five new poems and then proceeded to integrate them with some chitchat and comic characterizations. Her half hour reading was well received. Weeks later the artistic director of a theatre in Austin, Texas called and requested that Galloway come in January to Texas to perform. Since Galloway had performed her solo show, Out All Night and Lost My Shoes, a number of times in Austin previously, her Florida friends, myself included, urged her to create something new. Feeling a bit bullied by her friends, Galloway returned to her FSU poetry presentation on her computer disc and began the process of reshaping it into a performance piece.

A week prior to her booking in Austin, Texas, Galloway was talking to her mother in her parents’ kitchen about her new performance piece in process. As her mother was busy fixing brisket and thus only half listening, Galloway discussed the possibility of making a couple of the comic characters within the piece “fat” and then she read aloud some of the poems. Her mother, Edna, after hearing the title of one of the poems, “Lardo Weeping” and something about “fat” characters, assumed that the persona of this new performance piece in development—the one who changes in and out of the various characters—was not going to be her daughter, but rather some very large woman—a “Lardo.” Terry Galloway, who had not initially contemplated having the main character be someone other than herself was tickled by her mother’s idea because the artist longed to create a piece that was not as obviously autobiographical as her other performance pieces, Heart of a Dog and Out All Night and Lost My Shoes. Thus, Galloway’s mother’s misunderstanding—that the new show was going to feature a “Lardo”—was embraced wholeheartedly by the artist.

Still unsure as to whether this new “performance piece” would actually work—even with the reassurance that the show was booked and clearly promoted as a “work in progress”—Galloway tried out the performance piece in the upstairs study of her parents’ house. As a couple of close friends, her mother and I listened, Galloway with a pillow stuffed in her sweat suit and script in hand performed her first, informal, staged reading of, what was then christened, Lardo Weeping.

Lardo Weeping, from the start was a performance piece that combined poetry, stand up comedy, political diatribes, and invented comic characters. Galloway attempted to seamlessly interweave these genres as she told the tale of a day in the life of Dinah LaFarge, a character who was a fat, funny, broke, opinionated, agoraphobic woman. Or as one critic later described Dinah LaFarge, she was “a crackpot, but a crackpot who is somehow in control of her life” (Young). In the spring of l988, Galloway presented three different staged readings of Lardo Weeping in Austin, Texas; Tallahassee, Florida; and New York City before actually committing herself to a two week run at Capitol City Playhouse in Austin, Texas, at the end of summer, l988. In the interim between the staged readings and the first run of the show, we commissioned a costume designer, Margaret Wiley from Esther's Follies in Austin, Texas, to make a fat suit for Galloway to wear as Dinah LaFarge.

Lardo Weeping, from the start was a performance piece that combined poetry, stand up comedy, political diatribes, and invented comic characters. Galloway attempted to seamlessly interweave these genres as she told the tale of a day in the life of Dinah LaFarge, a character who was a fat, funny, broke, opinionated, agoraphobic woman. Or as one critic later described Dinah LaFarge, she was “a crackpot, but a crackpot who is somehow in control of her life” (Young). In the spring of l988, Galloway presented three different staged readings of Lardo Weeping in Austin, Texas; Tallahassee, Florida; and New York City before actually committing herself to a two week run at Capitol City Playhouse in Austin, Texas, at the end of summer, l988. In the interim between the staged readings and the first run of the show, we commissioned a costume designer, Margaret Wiley from Esther's Follies in Austin, Texas, to make a fat suit for Galloway to wear as Dinah LaFarge.

Since Austin, Texas, had always strongly supported and nurtured Galloway’s art, it came as no surprise when this first real run of the first real draft of Lardo Weeping garnered glowing reviews (Young, Walsh). But while the reviews were reassuring, comments from our feminist friends resonated long after the run. An excerpt from my journal entry after this first production:

• Feminist friend—Kate Adams—argues post-performance, that you can’t have a fat female performer on stage without addressing the issues of women and weight. She tells us to read Fat Is a Feminist Issue [. . . ].

• Ann Armstrong’s critique was [about Terry’s portrayal of the character]—that Lardo [i.e. Dinah LaFarge] moves sometimes realistically and sometimes like a comic book character. Really fat women, Ann claims, can’t dance like Lardo, can’t get up from the floor without holding on to something for balance.

• Both Terry and I [are] somewhat uncomfortable as technical /lighting person [for this production at Capitol City] is a very huge woman. Authenticity of show haunts us. We overcompensate by inviting her to spend days out at [Terry’s parents’] farm. (Nudd, “Notes”)

• Ann Armstrong’s critique was [about Terry’s portrayal of the character]—that Lardo [i.e. Dinah LaFarge] moves sometimes realistically and sometimes like a comic book character. Really fat women, Ann claims, can’t dance like Lardo, can’t get up from the floor without holding on to something for balance.

• Both Terry and I [are] somewhat uncomfortable as technical /lighting person [for this production at Capitol City] is a very huge woman. Authenticity of show haunts us. We overcompensate by inviting her to spend days out at [Terry’s parents’] farm. (Nudd, “Notes”)

It was also during this first production that Galloway and I realized that the only solo performances of large women that we were familiar with were literary characters (e.g. Pat Carroll playing Gertrude Stein) or stand up comics (e.g. Roseanne Barr, Thea Vidale). But our show was neither a historical rendering of a writer or a standup comedy routine; the obese, funny Dinah LaFarge was a fictional, theatrical creation of Terry Galloway.

Our friends’ comments and the particular circumstances of the production began to raise a number of questions about our representation of this fictional creation of Terry Galloway. Foremost among them was the issue of exactly what our responsibility was when placing a large female character on center stage and exactly to whom we would be held accountable. Further questions resonated: is it necessary or even possible for us to tell an “authentic” story of what life is like for a large, white woman in America? Must we give the expected, politically correct interpretation of obesity? And why is that women, including us, seem so concerned about Dinah’s size when there is so much more to Dinah’s personality—her politics, her eccentricity, her wit, her paranoia, her poverty, her poetical insights, her desire to be saved? And does Galloway’s physical performance of Dinah have to be labored? Can the free spirit of the plus-size Dinah be physically demonstrated within the confines of realism? And why are Galloway and I so internally terrified of the “mystery” of what the very large woman who served as our lighting technician “really thinks” of the show?

But while all these questions whirled around in our minds, the most revealing note in my journal entry after this first production revolves around the issue of authorial intent: “Terry argues that she is intent on creating a female Falstaff and that her character doesn’t have to address fat issues” (Nudd, “Notes”). Galloway’s succinct and provocative statement needs unpacking. We can start by tracing it’s autobiographical origin by reconsidering Galloway’s published description of her experience as an undergraduate playing Falstaff at the University of Texas’ Shakespeare at Winedale Program in 1971:

Now Henry IV was my favorite history play; and Part I was my favorite part of it; and the Falstaff of Part I was my favorite role. We hit the great tavern scene where Hal in effect banishes Falstaff. I have always felt that reckless endangerment that comes with love, and I truly loved Falstaff. I felt that love and also an anger and protectiveness. I knew that Hal would triumph and go on to be King; and Falstaff and all the misfits would get left behind. And being as I was (and am) deaf and a woman, and also at the time, oh, just poor as shit, I suddenly fell into the language. There was no division between what Falstaff had to say and what I was feeling at that moment. Falstaff’s great defense of himself and his kind became my own defense of him, and of myself, and all of us who were destined to be the comic relief, the dispossessed, those for whom destiny had little to say—most of us really. And my friend Jan who was playing Hal felt the language turn real so he kept turning it—that is what we had aimed for when we rehearsed. And the audience felt it too. That is what they had come to experience. And there we all were, all of us caught in that moment. Everything turned stark still, the temperature dropped, and we were all in that fictitious and real moment together, all of us—audience, performers and whatever ghosts were in the rafters.

But did the experience mean anything? It was after all simply a performance by a handful of university students witnessed by a mere three hundred people in a barn in a Texas town so small it wasn’t even on the state map. The performance was poorly documented—it wasn’t reviewed, no video was made, and there weren’t even any photographs of it.

Here are some of the meanings I can articulate. I had been swept up in theatre, the epiphanic moment. And not only was I caught up in the moment, I was one of its prime agents: I was the great loved figure, the comic male who throws the realistic male, the handsome prince into the shadow. As a comic male I could stand up to the realistic male. And I could win. I could seduce by amusement and win over the hearts of everybody privy to that performance. The audience loved Falstaff and loved the way I portrayed the character Shakespeare had created. And because they loved that character and my presentation of him, they would not so easily forgive Hal the cold, dismissive practicality of his “friendship”; nor, after that scene, would they ever entirely trust him or the elasticity of his “nobility.” Again Falstaff had not been defeated. Again. He had been saved through performance. Again. And the performer (in this case, me) had saved him. Again, I was part of that continuum. But I was the new slant, the new minority that had been encompassed by the fiction of Falstaff; and having been so encompassed, could newly embody him. (Galloway, “Taken” 96-97)

But did the experience mean anything? It was after all simply a performance by a handful of university students witnessed by a mere three hundred people in a barn in a Texas town so small it wasn’t even on the state map. The performance was poorly documented—it wasn’t reviewed, no video was made, and there weren’t even any photographs of it.

Here are some of the meanings I can articulate. I had been swept up in theatre, the epiphanic moment. And not only was I caught up in the moment, I was one of its prime agents: I was the great loved figure, the comic male who throws the realistic male, the handsome prince into the shadow. As a comic male I could stand up to the realistic male. And I could win. I could seduce by amusement and win over the hearts of everybody privy to that performance. The audience loved Falstaff and loved the way I portrayed the character Shakespeare had created. And because they loved that character and my presentation of him, they would not so easily forgive Hal the cold, dismissive practicality of his “friendship”; nor, after that scene, would they ever entirely trust him or the elasticity of his “nobility.” Again Falstaff had not been defeated. Again. He had been saved through performance. Again. And the performer (in this case, me) had saved him. Again, I was part of that continuum. But I was the new slant, the new minority that had been encompassed by the fiction of Falstaff; and having been so encompassed, could newly embody him. (Galloway, “Taken” 96-97)

Thus, we come to understand how the experience of playing one of Shakespeare’s most beloved comic male characters could later serve as the impetus for Galloway to create Dinah LaFarge, a character whose great defense of herself and her kind would ideally become Galloway’s defense of all women like LaFarge—a funny, middle-aged, disempowered plus-size, public intellectual. Yet when we reflect further on that salient field note—“Terry argues that she is intent on creating a female Falstaff and that her character doesn’t have to address fat issues”—Galloway and I are also reminded of our naivety. Galloway, reflecting on this early comment duly notes:

I didn’t know I was stepping into a mine field when I made the character fat. By making her fat, I thought I was dramatizing all those things that I hold dear that seemed symbolized by her girth—her breadth of mind, her liberalism, her outspokenness, her overflowing generosities and anxieties. To me Dinah physically embodied a wall, a last line in the defense of my own kind—the losers, the disposed, the disregarded. I genuinely didn’t realize it might be read differently by an audience—and boy was I pissed that it was. (Interview)

What happened thus from the start, was that our invisible feminist dramaturges, the feminist community, was insisting that the playwright/performer and director/dramaturge had to “address fat issues.” We felt the pressure; we heard the insistent call; we, quite honestly, resented it and initially resisted it.

Now, in retrospect, I see the feminists’ insistence on “addressing fat issues” (a theme that runs through the show’s production history) quite differently than I did initially. Now I see it as feminists serving as co-creators, in the vein that Erik Ehn called for in his keynote address in the 2002 conference of Literary Managers and Dramaturgs of the Americas. Here D.J. Hopkins summarizes Ehn’s “radical proposition” which is “at odds with the most common assumptions about dramaturgy”:

Rather than contributing to a text in the service of production, the dramaturg’s contribution could be independent, serving not as a corollary but as a supplement to the text. Research should trouble the production, not simplify it, and dramaturgy should create complications alongside, parallel to, and in conjunction with the playwright’s text. In the case of co-creative dramaturgy, the dramaturg’s contribution to production would be conceptual work that may have no direct relation to the playwright’s script, that may precede, and even exceed, the playwright’s text. (Hopkins, 5)

A Character in Crisis, l989-90

Audience reaction to the next two performances of Lardo Weeping gave us a temporary respite from the critical obsession concerning Dinah LaFarge’s body politic. A staged reading of the then current draft of Lardo Weeping for the Wildacres Writers Festival in North Carolina gave Galloway an audience of writers who took pure delight in the language of the piece. A number of months later, a benefit performance of Lardo Weeping in Florida served to absolve us of any implication of not being “politically correct” when we learned that our sold-out evening show netted over $2000 for Tallahassee AIDS Support Services.

But our momentary absolution dissolved when we presented the show for festivals in Indiana and Oklahoma. While some critics at these shows, like Linda Park-Fuller, astutely noted the range of issues from animal rights to Soviet/American relations that Dinah LaFarge in Lardo Weeping addressed, that other issue, Dinah’s weight, is the one that clearly was still foremost on most audience members’ minds. People would tell us how the show inspired female audience members to share “weight” stories. My friend, Daun Kendig, for example, told us of an audience member who told her a twenty-minute story at dinner after the show about a time in her life when she was very fat and she went home to her mother’s and slept for two weeks, before waking up and deciding to do something. It was clear that Lardo Weeping worked, at this stage of development, as a catalyst that elicited women’s personal struggles/opinions/stories on weight.

The most intense reactions from feminists, however, centered on the topic of appropriation. Before sharing this next anecdote, however, it is import to note that Terry Galloway, an expert at lip reading is medically deaf, though not culturally Deaf. Because she speaks clearly, most audience members do not know she is deaf, though often pre-show publicity will capitalize upon her being a deaf performer. Immediately after Galloway’s performance of Lardo Weeping in Indiana, a very large academic feminist muttered to some friends of mine as she exited from an elevator, “Fat jokes, nothing but fat jokes. When (Galloway) starts making deaf jokes, then maybe I’ll listen.” When my friends shared with me this plus-size feminist’s parting shot, I waited a day or two before passing the comment on to Galloway. When I did, Galloway’s immediate response was defensive, angry, and pointed: “No one has the monopoly on weight” (Nudd, “Notes”). And a moment later Galloway’s addendum was to point out the irony in that both her previous autobiographical shows, Heart of a Dog and Out All Night and Lost My Shoes, contained more than their share of deaf jokes.

The issue of Galloway’s “right” to perform a large woman also surfaced at the Oklahoma performance. In the question and answer period that followed the show, an extremely large white woman in the audience politely asked Galloway if she had ever been fat. When Galloway responded that there were times in her life when she was “fatter” than she was now, but never “truly fat,” my heart rate increased. But, in contrast to the remark made by the woman on the Indiana elevator, this audience member in Oklahoma claimed, “Well, it’s clear from seeing this show that you have the soul of a fat woman” (Nudd, “Notes”).

So at this point in the development of Lardo Weeping, Galloway and I found ourselves at an impasse. A feminist colleague in Performance Studies, Kay Holley, explained the situation most clearly when she said that on the one hand, she felt that the petite Galloway playing the obese Dinah LaFarge could always be considered by some audience members as the “moral equivalent of black face” (Nudd, “Notes”). Kay, went on, however, to second guess her own motivation for having made this declaration. In all honestly, she explained, perhaps she was leveling the charge of appropriation because she secretly desired to play Dinah LaFarge herself. And from there, the conversation continued as she too shared personal stories about what it meant to her—and to others in her Overeaters Anonymous group—to be a large, white woman in American society.

While Galloway and I benefited quite directly from hearing these personal stories from feminists over their own struggles with weight issues, the question of Galloway’s right to perform the obese Dinah LaFarge continued to haunt me and bug Terry. In my journal entries at this time, I find long letters and summaries of lengthy conversations with friends in which I am trying out different possible solutions to dealing with the charge of appropriation. Perhaps rather than Dinah LaFarge being obese, we could just make her dumpy. Perhaps we should just hand over the text to Kay Holley to perform. Perhaps we should just be extremely up front about the fact that it’s a normal weight actress playing a large woman by beginning and ending the show with a frame of an actress getting into and then out of her fat suit. Perhaps we should switch genres, rather than Lardo Weeping being a theatre piece, we might make a film or video in which we could have Dinah LaFarge be at different weights throughout (Nudd, “Notes”).

But none of these solutions ultimately rang true for us. To make Dinah dumpy, rather than fat, seemed a cop-out—we would sacrifice our original intent of creating a female Falstaff. To give up the script to a physically larger actress was tempting but ultimately impossible, for we both knew that the script was not finished yet. Galloway and I refine her solo pieces through the process of rehearsing, performing, conversing, rewriting, and we had not yet arrived at the point where we would be comfortable surrendering the script. To switch genres was possible, but at the time we didn’t have the technical expertise in film or video or the necessary financial backing to pull it off. Finally, the idea of framing the show with Galloway putting on and pulling off the fat suit was not an ideal choice because we didn’t have the time to completely re-conceive the show in this manner before the next scheduled booking; moreover, we were concerned about how such a Brechtian alienation technique would affect audience empathy for our Dinah.

In the summer months that followed the Indiana and Oklahoma productions, I continued to read feminist performance theory and criticism. Jill Dolan’s Feminist Spectator as Critic, Linda Hart’s Making a Spectacle, Rita Felski’s Beyond Feminist Aesthetics and essays on the work of Karen Finley, Heiner Mueller, Marsha Norman [7]. In my journal entries, I summarize the theorists’ claims about what realism can and cannot do. I struggle to discover where Lardo fits. An essay by Jill Dolan—arguing that audience members don’t find Jessie Cates death in ‘night Mother a true tragedy because Kathy Bates was overweight—works to reinforce, as I note in my journal, “my already ingrained belief that realism only reinforces the status quo and all its sordid ideologies” (Nudd, “Notes”).

At this point, my theoretical readings prompt me to believe that Lardo isn’t “risky enough,” so I come up with a new idea (Nudd, “Notes”). An idea that may work to answer both this newly self-imposed charge that Lardo isn’t experimental enough as well as the charge of appropriation that continues to concern me. I remember a yet unproduced song/poem that Galloway wrote years ago called “Ms. Bones.” “Ms. Bones” was an anorexic striptease number in which the character pulls off strip after strip of velcroed–on flesh until she is reduced to her skeletal self. I envision Galloway rewriting the “Ms. Bones” piece and using it as the end of Lardo Weeping. Having the obese Dinah LaFarge literally deconstruct, I reason, would serve to answer once and for all the appropriation charge. Galloway is genuinely enthusiastic about the idea; she begins to rewrite “Ms. Bones” from the obese Dinah LaFarge’s perspective. And we commission a visual artist friend of ours in Philadelphia to begin constructing a body that Galloway/Dinah will be able to rip off in her literal striptease for the show’s ending.

But while I would have liked to have had the satisfaction of reveling in this late summer epiphany, the feminists theorists wouldn’t allow me to. The last book on my summer reading list is Felski’s Beyond Feminist Aesthetics. In focusing on contemporary fiction, Felski provides a sympathetic appraisal of women’s confessional forms and argues that the avant-garde is overly elitist. Suddenly, I begin to “worry about undercutting the ‘realism’ in Lardo—which is after all very moving” (Nudd, “Notes”). I question how we can possibly reconcile our contradictory desires to retain the authenticity of Dinah LaFarge’s personal and moving experiences as a full-figured woman in American society with our desire to let her literally deconstruct at the end of the show. At the time, I note: “More than ever I’m excited about Lardo—what it does, what it is trying to do. Somehow I want it all.” All is articulated in my journal as “confessional,” “parodic,” “postmodern,” “serious,” “poetic,” “philosophical,” and “political.” I conclude: “Somehow I think Lardo can be all this—but I’m not sure exactly how” (Nudd, “Notes”).

A Character Deconstructs Before Her Time, Spring and Summer l991

In the spring of l991, Galloway, while touring with an excerpted version of Out All Night and Lost My Shoes with PS 122 Field Trips, briefly discusses with PS 122’s artistic direction, Mark Russell, the anorexic striptease number she is working on for Lardo Weeping. Russell begins to investigate getting some money to help Galloway to develop the piece. A grant from the PEW Foundation comes through which enables Galloway to fly to Philadelphia, present the striptease excerpt and shop with our visual artist friend, Teresa Jaynes, for the fabric materials she will use to construct Dinah’s new body.

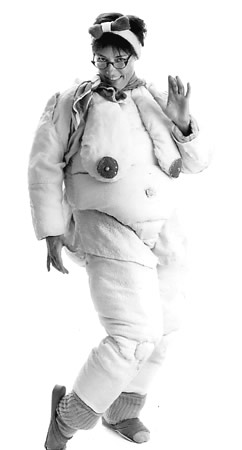

Lardo Weeping is booked for a month run in August in Austin, Texas. During the preceding summer months, Teresa Jaynes dutifully begins to construct Dinah’s body. Jaynes first constructs an undersuit that closely fits Galloway’s own body, it is made of a dark orange, raw looking polyester material. Then Jaynes begins to construct Dinah’s body. Using a light pink, soft material and lots of stuffing, she begins to build body parts—wrap-around legs with the Velcro seams in the back, a removable torso with Velcroed seams where arms and legs are attached, Velcroed flaps of skin on the arms, breasts which detach from the torso, nipples which detach form the breasts. As the imposed deadline for completion gets closer and closer, Jaynes enlists her mother and grandmother’s help with the body’s construction, and then, during the final week, she enlists the help of all her close women friends in Philadelphia.

Two days before the final dress rehearsal, thanks primarily to what Jaynes referred to as her “lesbian sweatshop” in Philadelphia, Dinah’s body arrives in Texas, Federal Express (Nudd, “Notes”). The body is visually and solidly beautiful.

Our first order of business is to buy Dinah some clothes. We are surprised to discover that feminist politics even invade this simple task. For as Galloway and I, both “normal” size women, set out to buy a dress for our full figured, 56-54-65 friend Dinah at Lane Bryant, we argue in the car over whether to tell the clerk we are purchasing the dress for a theatrical character or whether we should tell the clerk we are seeking a dress for a close relative of Galloway. I passionately argue that we should be straightforward, but I know my vote is overruled when I discover Galloway, at Lane Bryant, conversing with the clerks about her grandmother’s upcoming birthday celebration. I do understand though Galloway’s need to fictionalize. Galloway didn’t want to violate the “spirit of Lane Bryant”; she desperately wanted the Lane Bryant folks to feel her intentions were honorable. To say she was buying clothes for a fat female stage character would most likely be interpreted in this society, as buying the clothes for a “joke.” Galloway’s strategy works, for not only are the clerks especially helpful, but also a couple of very large customers at Lane Bryant help us too by telling us of the only store in Austin, Texas, that is going to have in its stock a sexy teddy large enough to fit Terry’s grandmother. But while Galloway’s strategy works, it sill makes me uncomfortable. My Northern self still is ill at ease at bonding with strangers and my old Roman Catholic self, oddly in sympathy with my feminist self, doesn’t approve of lying to these large Lane Bryant women whose reality we are honestly trying to represent in Lardo Weeping. But Galloway’s Southern, friendly, agnostic self reassures me that our intentions remain honorable.

We end up purchasing a midnight blue, sexy teddy at Solo Mio, a classy blue dress from Lane Bryant and a polyester, floral muumuu from Walmart. We cut the floral material of the muumuu and attach it onto the bottom of the Lane Bryant dress to make it one full-length dress. But before we have time to revel in having constructed the perfect dress for Dinah LaFarge, a new nightmare begins. Dinah's body, we discover during our technical rehearsals, is a wonderful and evocative piece of art, as long as Galloway does not move. But, of course, Galloway traverses up and down and all over the stage for an hour before the final striptease number comes near the end of the show. What happens literally is that Dinah’s body deconstructs before its time. In other words, by the climax of the show when Dinah playfully and evocatively opens her dress to begin the striptease, Dinah’s body had already become undone, the Velcroed seams that combined the parts of her body have already unraveled clandestinely underneath her dress during the course of the performance.

We end up purchasing a midnight blue, sexy teddy at Solo Mio, a classy blue dress from Lane Bryant and a polyester, floral muumuu from Walmart. We cut the floral material of the muumuu and attach it onto the bottom of the Lane Bryant dress to make it one full-length dress. But before we have time to revel in having constructed the perfect dress for Dinah LaFarge, a new nightmare begins. Dinah's body, we discover during our technical rehearsals, is a wonderful and evocative piece of art, as long as Galloway does not move. But, of course, Galloway traverses up and down and all over the stage for an hour before the final striptease number comes near the end of the show. What happens literally is that Dinah’s body deconstructs before its time. In other words, by the climax of the show when Dinah playfully and evocatively opens her dress to begin the striptease, Dinah’s body had already become undone, the Velcroed seams that combined the parts of her body have already unraveled clandestinely underneath her dress during the course of the performance.[Taking it All Off, the video below (shot and edited by Diane Wilkins), includes the striptease scene of Lardo Weeping, performed for video in 1993]:

It was during this month’s run that Galloway and I learned the true difference between a visual artist and a costume technologist, for Jaynes’ body for Dinah LaFarge was visually and immovably beautiful, and thus impractical for the stage. For the run of the show, my main objective became, out of sheer necessity, to make Dinah’s costumed body work theatrically, that is, to supply the audience with an illusion of a “real” body until the final striptease near the end of the show. In my journal notes, I candidly admit: “Terry is so angry about the suit not working, that it’s like pulling teeth to get her to even try on the damn thing so that I can see where I should start making adjustments” (Nudd, “Notes”). With occasional help from Terry’s mother and sister, I make “adjustments” designed solely to prevent the costume from unraveling before its time. Through the course of the run, the spaghetti straps of the teddy are replaced with huge straps of elastic which more effectively hold Dinah’s breasts in place; a Little-Lotta-like skirt is sewn on to the bottom of the teddy to cover up where the Velcroed seams are splitting on Dinah’s rear end; and extra bits of pink fabric are added at the top of Dinah’s arms and legs to cover up where the Velcroed seams have disconnected. The nightmare of trying to prevent Dinah’s body from deconstructing before its time was not without its comic moments however. On the night that the reviewer from the Austin-American Statesman came, I sat in the audience and, during an especially poignant early monologue in the show, watched one of Dinah’s breasts fall slowly underneath her dress from her chest to her waist area, landing on the stage floor. The reviewer never commented on the mishap, but the image of that falling breast typifies the technical problems we were having with the body at the time.

All in all, the month’s run in Austin, Texas, while most certainly trying, was a pivotal turning point in the development of Lardo Weeping. Once again, our friends and the reviewers proved to be more than supportive. Even though Dinah’s body didn’t technically work as easily as we envisioned it could, it still worked enough for us to give the audience a general sense of where we were headed.

Yet I want to pause here to reflect momentarily on “poor theatre” and its relationship to feminist dramaturgy. When something significant isn’t working and there aren’t the resources to fix it, the dramaturgy suffers. In our case, during this particular run, the costume of the body wasn’t working, and we did not have the immediate resources or know-how to expediently fix it. We did not have the money to fly our costume designer from Philadelphia to Austin, Texas to save the day, so Galloway and I were forced by necessity to take on yet another role, costumer, a role to which we are both determinedly ill-suited. (Our sewing skills having never surpassed the elementary thread-and-needle stage and our technical skills not moving much beyond the duct tape-as-panacea stage.)

Indeed, attending to the day-to-day technical repair of Dinah’s body was so time-consuming and frustrating that neither Galloway nor I had the time or the energy to think through the more significant philosophical questions concerning the body politics of Dinah’s identity as they were articulated in this latest draft/production of Lardo Weeping. I recall, for example, Galloway’s feminist sister sharing with us a fellow audience members’ response to the show. The female college student, who sat next to Terry’s sister, concluded that Dinah was an eccentric woman who would put on a fat suit every morning and strip it off every night, that Dinah got some perverse and inexplicable pleasure in this daily routine. Because I didn’t have the energy or the time, as I was too busy with my needle, to contemplate what this undergraduate reading actually revealed about Lardo Weeping as it was currently staged, I remember mocking the undergraduate’s Dinah-as-fatsuit-fetishist interpretation, facilely dismissing it as yet another unenlightened audience member who couldn’t see the world through any lens but realism. In retrospect, I believe I swept aside this undergraduate’s interpretation (which was indeed a valid reading of the production at the time) simply because I had completely abandoned my directing/dramaturgical duties having been drafted, against my will, into the role of costumer.

A month after the show, however, I was ready to begin to contemplate what was working and what wasn’t in this newest rendition of Lardo Weeping. And it was at this opportune moment, that Lynn Miller, a Performance Studies colleague, called me to talk about the show.

In our conversation, Miller informs me that she and her friends who saw the show during the last week of its run in Austin spent hours and hours afterward discussing it. Miller summarizes her and her feminist friends’ observations. In essence, Miller claims that the first 55 minutes of the show work extremely well, but the last 15 minutes are problematic. She argues that Galloway’s and my vision at the end is not clear, that the striptease finale is too ambiguous. Miller tells us that in the show’s first 55 minutes, she and her friends come to know and love Dinah in all her complexity; they were charmed by her politics, her outspokenness, her wit. Then suddenly they watch this character tear off her body parts and the show ends with another character, a small woman in a raw body suit, standing before the audience. Miller wants to know what happened to Dinah LaFarge? Where exactly did Dinah—the character that the audience has come to love and admire—actually go? Why is Dinah, who has seemed so at ease with her body through the show, now ripping off her body parts? Is Dinah’s striptease meant to be liberating or masochistic? And also who exactly is this smaller woman that is standing before the audience at the end of the piece? Finally, Miller ponders whether the visual image of seeing an obese woman strip off her body parts—regardless of the content of the language that accompanies it—works to reinforce the age old cliché that within every fat woman is a little woman striving to get out. Millers’ questions concerning Dinah’s identity resonate deeply and Galloway and I seriously debate the issues raised and strive to clarify our vision—philosophically and dramatically.

A Character Reconstructs Just In Time, Fall 1991

Before our scheduled January “debut” at PS 122 in New York City, we have two mini-bookings to prompt us to refine the show. In late October, Lardo Weeping was scheduled to be presented at the Speech Communication Association Convention hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, and in early December at a theatre in Tallahassee, Florida. Thus, Galloway and I have only the autumn months to devise and try out some theatrical answers to Miller’s difficult queries before our opening in New York.

Enlisting the help of some costumers to redo the body suit was our first priority. M. L. Baker, a costume technologist in the Theatre Department at Florida State University and our friend, Patti Dominguez, who costumed a local theatrical troupe’s shows, came to our aid. The costumers began by making Dinah’s body look less cartoonish and more “lived in” and they strove to make Dinah’s body parts truly hold together until the moment in the show where Galloway rips them off. And much to the performer’s relief, the costumers also make the fat suit much lighter, thus making it easier and more pleasurable for Galloway to wear.

Miller’s concerns keep echoing, however, so much that I find myself perhaps rather obsessively exploring the feminist political issues inherent in the ending of Lardo Weeping with my graduate students in a “Rhetoric of Women’s Issues” seminar. After explaining the striptease ending of the Austin show and Miller’s subsequent queries, I ask the students for their views. We discuss that the visual image of Dinah stripping off her body parts is undeniably a powerful image, an image that both indicts society and also reveals Dinah’s own anger, despair and desire to escape from her body. And we agree that whatever is underneath the stripped-off body parts is undeniably symbolic. One of my students, Steve Woods, suggests that once the body parts are shed a jar of brains should be revealed. I laugh, because, of course I understand his point—what’s underneath it all is undeniably Dinah’s consciousness. But, most certainly, the visual image of a jar of brains is far too Frankenstein-like for my tastes.

Days later, Galloway and I agree that Miller’s frustration with the admirable Dinah disappearing at the end of the show seems to have an easy solution; in the denouement, Galloway and I decide, Dinah will reconstruct. She will literally pull herself back together again in the final few moments of the show. But we know that Dinah reconstructing is only a partial answer to Miller’s pointed concerns. We realize that our vision of the ending is still not clear, to us or to a potential audience. And it is at this timely moment that another one of my graduate students, Greg Tillman, knocks on my office door.

Greg shows me a photograph, the cover of an academic journal on women and art. The photo is divided into twelve sections, each one showing a photo of a torso of a woman. In each photo, the same woman is pulling her black blouse open and underneath something different is revealed—in one a Picasso-like image of a woman, in another Christian imagery, in another tin foil, in another a psychedelic print reminiscent of the sixties. . . I take the photo home to show Terry and BINGO we know we’ve got it. The problem was that we kept thinking that there was one thing underneath Dinah’s fat, but actually postmodernism has taught us that there is no core, that we are made up of all these contradictory selves only some of which we are actually aware of. So we talk initially about having multiple panels, perhaps having Dinah pull them off in succession, but in the end she just gets down to flesh. Next we hit upon Mary Collins’ old Esther Follies routine when she sings the Patsy Cline song, “I Fall to Pieces” while pulling out all the mementos from her last lover from inside her dress: his ring, his photo, a record album. . . I recall Robert Pack’s poem, “Love” which works on the same principle—the boy reaches for the girl’s breast and ends up pulling out books, theatre tickets, a tie, and a couple of rabbits. . . We sit with our roommate Beatrice and throw out ideas of what Dinah LaFarge could discover in her body—a high heel shoe? A Judy Chicago dinner plate? A baby? And then when Terry says –“no, a baby is too predictable,” Bea suggests a phone. We laugh envisioning the long umbilical cord (which would suggest the baby) then turning into a phone. We are tickled by the ideas. (Nudd, “Notes”).

And so we go back to our costumers and they begin to build into Dinah’s fat suit the images we want—from the belly button an umbilical cord which when pulled bares a telephone; a removable vagina that is indeed a Judy Chicago dinner plate. And the costumers add one of their own—when Dinah pulls the fleshy strip off her right arm, an American flag appears. Galloway is so enthusiastic, she returns to her computer and rewrites the striptease to incorporate and comment on all that Dinah’s body has come to mean to Galloway, to the costumers, to Dinah, to society.

By the time of our scheduled performance for the national SCA convention in Atlanta, Dinah’s body is not completely finished, but most certainly workable enough for Galloway to perform in. Booked as the second program at the convention, we are amazed when two hundred people show up in the Grand Ballroom of the hotel to watch the performance. Feedback from feminist friends in Performance Studies after this performance works once again to help us refine our ideas.

For example, in the middle of a conversation in a very crowded restaurant the morning after the performance, Linda Park Fuller abruptly says, “Oh, and another thing, Terry, you can’t believe how much Lardo’s strip resonates for someone who has recently had a mastectomy.” Linda, Terry and I laugh so loud and so long that a number of guests at other tables look up from their eggs benedict to stare at us (Nudd, “Notes”). Galloway and I laugh because, for us, there was no direct or implied image in the language of the striptease that suggested a mastectomy. Dinah’s striptease as performed in Atlanta consciously encouraged the audience to see women’s breasts as pornographic fetishes for men, as a prescribed nurturing link between mother and daughter; as an opportune place for Steve McQueen, in one particular film, to store his tobacco. It did not occur to either Galloway or me, until Park-Fuller noted it, that of course the visual image of Dinah shedding her breasts would parallel a mastectomy in some audience members’ minds. So once again a comment from a feminist prompts Galloway and I to refine our vision. When we return to Tallahassee, our costumers are instructed to put mastectomy scars under each of Dinah’s breasts and Galloway once again returns to her computer. In Galloway’s rewrite of the relevant section of the striptease, Dinah talks to her mother on her “hotline to her inner self.”

Hello? Mom?

Mother?!

A woman you say has a duty

To her man, to her kids, to her church

And to beauty.

As much as it pains her, as much as it pains her.

Maybe that’s why mother binged and purged.

Maybe that’s why mother stayed married.

Maybe that why mother wrapped meat for minimum wage.

Maybe that’s why mother said, “No!”

When the Doctors told her “Ms. LaFarge, these two have really got to go.”

(SHE rips off one breast, puts it to her mouth like a cigar.)

The only thing radical about my Mother was her mastectomy.

Har. Har.

(SHE rips off the other breast.)

I’m glad to get these off my chest.

Her last words

That last night were

“Honey, this disease is just like you.

It’s got the most ferocious of ferocious appetites.”

Yes, definitely how my Mother felt

Last time I laid my head against her breast.

That absence. (Galloway, Lardo, ts., l993, 25-27)

Mother?!

A woman you say has a duty

To her man, to her kids, to her church

And to beauty.

As much as it pains her, as much as it pains her.

Maybe that’s why mother binged and purged.

Maybe that’s why mother stayed married.

Maybe that why mother wrapped meat for minimum wage.

Maybe that’s why mother said, “No!”

When the Doctors told her “Ms. LaFarge, these two have really got to go.”

(SHE rips off one breast, puts it to her mouth like a cigar.)

The only thing radical about my Mother was her mastectomy.

Har. Har.

(SHE rips off the other breast.)

I’m glad to get these off my chest.

Her last words

That last night were

“Honey, this disease is just like you.

It’s got the most ferocious of ferocious appetites.”

Yes, definitely how my Mother felt

Last time I laid my head against her breast.

That absence. (Galloway, Lardo, ts., l993, 25-27)

When Park-Fuller saw Dinah’s striptease in Atlanta she understood that we were exploring the ways that Dinah’s body was both literally and culturally constructed; her input indeed pushed us to complicate our vision.

In describing how one line from a feminist spectator in a crowded conference hotel restaurant in Atlanta prompted Galloway to refine Lardo’s language, I am citing one example to stand for many. Comments from other feminists in Performance Studies—Dixie Gray, Daun Kendig, Nathan Stucky, Annette Martin, Charlotte Stewart, Sherry Dailey, Sue Davis, Randy Hill—worked in similar ways in the course of developing Lardo Weeping to help us refine particular moments in the show. While their comments or concerns may not have had a major impact on our overall vision of who Dinah LaFarge was, they did help to make our vision of her character at particular moments in the show more fun, more clear, more poignant, more evocative, more complicated or more disturbing.

And of course the insights of our feminist friends in Tallahassee worked in a similar vein; we were grateful for more “refining” suggestions after our short December run. But what was most significant about this late Tallahassee run is that the costumers got to see Dinah’s body in performance. They were able to gauge what was working and what was still not quite working and make the necessary adjustments. Most delightful to us, was that we made enough money from the run to pay them (Nudd, “Notes”).

In the last autumn months before our New York debut, Galloway explored the possibility of the scheduled run in January at P.S. 122 being co-produced by The Women’s Project. After reading the script, Julia Miles, the artistic director of The Women’s Project at the time, enthusiastically agreed to co-produce the show. There followed a number of phone conversations with Julia Miles and a fax from Liz Diamond, a New York director affiliated with The Women’s Project. The feedback from the feminists associated with The Women’s Project initially affirmed Galloway’s and my vision of Dinah LaFarge. Liz Diamond writes to Galloway:

Dinah LaFarge is a fabulous creation first of all. A fantastic, philosophizing beached whale, she is both grotesque and enormously (excuse pun) sympathetic. I love her poetic flights, her obsession to not obsess about food; the digest she keeps of everything she puts in her mouth is hilarious and very sad. I love the contradictions you build into her portrait: she avoids taking action to change her life by constantly talking about changing her life. She is both a monstrous bundle of pathologies and a monstrous bundle of creative energy. Her removal of great hunks of flesh is a spectacular coup de theatre. (Nudd, “Notes”)

But the three-paged, single-spaced fax from Diamond did more than just affirm Dinah as a character and Galloway as a writer. For Liz Diamond was an astute critic who could articulate the philosophical issues surrounding Dinah’s identity which we were unable to articulate at the time.

I realize this may sound hopelessly grandiose, but damn it, Terry, I think your play is circling around some big, funny, and tragic ideas about the human condition—the fact that we are all trapped in our flesh, in our earthly bodies and yet have this voice, this self or soul that is constantly rattling the cage, trying to break free. . . and, even more tragic-farcically, we secretly are very happy to be stuck in our heavy, earth bound bodies because it’s a great excuse. For an artist, which Dinah certainly is, the body, whether skinny or fat is going to be an encumbrance. The body is death. The Mind is pure spirit, eternal life. I may be going way off the deep end here but I think you should really dig deeper into the two central images of the play: Automatic Mind Control and Dinah’s huge body. The event of the play lies in the relationship between these two powerful metaphors. In Dinah LaFarge there is a war going on between Mind and Body, between the spirit and the flesh. Right now, the piece seems to back off, or circle around this extraordinary conflict. It sort of rambles off when it could explode. (Nudd, “Notes,” ellipsis in this paragraph is Diamond’s.)

Paying close attention to the striptease ending and Dinah’s reconstruction, Liz Diamond goes on to note:

I don’t think [Dinah’s] setting us up to be witnesses to a horrible act of self-mutilation or public hari-kari, she seems to essentially buoyant a spirit for that. . . does she aspire to some kind of magnificent transfiguration? Does she succeed? Does she fail? There’s almost a kind of attempt at transubstantiation in ripping off her flesh, as if she aspires to float upward! Your writing strikes me as too wonderfully ironic to fall for some kind of cornball romantic ending of Dinah Transformed, or Dinah Redeemed, but there is a kind of greatness in her attempt. I love Dinah and just can’t help feeling that her story is a little bigger (again, please don’t die from these puns) than the sad but familiar one of the woman who loathes her body and seeks to escape. I don’t feel that Dinah is driven by a negative impulse (self-hatred) but by a positive impulse (an urgent, shining belief in her own poetic voice) that is constantly being undermined-hilariously and tragically-by her very human appetites. (Nudd, “Notes,” ellipsis in this paragraph is Diamond’s.)

Liz Diamond’s description of the larger philosophical questions, which Lardo Weeping seemed to be “backing off from or circling around, “ prompted Galloway and I to search for more moments in the show where our own philosophical position concerning Dinah’s identity could be more clearly and theatrically argued.

For example, Diamond’s fax encouraged us also to develop the “Automatic Mind Command” image in the show much more. In the play, Lardo Weeping, Dinah LaFarge is an avid reader of both “Art and Garbage” (Galloway, Lardo 6). After reading an advertisement in The Weekly World News, Dinah purchased Automatic Mind Command, a device that secretly works to get other people to do one’s bidding. As a theatrical conceit, we learn early in Lardo Weeping that Dinah LaFarge’s expert use of Automatic Mind Command is indeed responsible for this particular audience showing up at this particular theatre to listen to this particular woman, that is, her. With full knowledge that the evening’s proceeds are destined for Dinah’s pocket, the audience is comically assumed to be under Dinah’s power.

With Diamond’s prompting, Galloway and I returned to the script to see what else was theatrically possible with Automatic Mind Command. In the version of the script that Diamond had read, Automatic Mind Command had been used only comically. Because of Diamond’s prompting, we built in moments later in the play, when Dinah is feeling more dire about her life, in which Dinah LaFarge’s Automatic Mind Command power seems to be waning. In doing this, the comic theatrical device turned poignant, suggesting that Dinah, in an attempt to understand her current desperate situation, was again wrestling with the age-old philosophical question: “Will or circumstance?”

A Character’s Fifteen Minutes of Fame, l992-2007

After appearing in New York City, Dinah LaFarge traveled a great deal the following year, in 1993, to Seattle, Austin and London. After that, between 1994-1997, Dinah would only venture out for a weekend or a week at most; she did not discriminate geographically, appearing in Mexico City for example, as well as Fairmont, West Virginia. Dinah was brought out of her premature retirement for a 2002 gig at the University of Texas and she’s currently scheduled to make an appearance next spring in our hometown of Tallahaseee, Florida. Admittedly, in the decade and a half following the l992 NYC showing, Dinah’s character changed in only minor ways.

One could easily assume that since Dinah’s character was more fully, if not completely, developed that the feminist dramaturgy stopped. But it didn’t entirely, for certain shows for certain audiences in certain locations demand dramaturgical interventions. More simply, Dinah’s body and character changes with cultural and historical circumstances, and a flexible feminist dramaturgy needs to continually keep that in mind. Two extended examples will suffice to illustrate this last point.

Let us first consider our preparatory work for a month-long 1993 production in London. In contemplating a British audience, Galloway and I had to consider what American allusions would escape them. We worried about this section of the script, for example, where Dinah bemoans her fate.

Emily [Dickinson] was not the last to have known the pangs of despised manuscripts. My genius too has been slighted by the gold-fueled world. Judge for yourselves.

A certain alphabet network—which shall remain nameless—was offered a chance in a lifetime opportunity to produce my proposed teleplay—an intellectual revision of The Honeymooners in which Ralph and Alice Cramden are replaced by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Foolishly I offered those puffbrains in charge of programming not just a host at the series but a shot at me! Who better for the role of Gertrude Stein than moi! No, judge for yourselves, judge for yourselves.

(SHE rummages for the script, pulls out a huge mother of a script titled The Honeymooners—The Next Generation.)

This is one of Gertrude’s key monologues. I’ll read you a short excerpt.

(SHE doffs glasses, headband and sits on a bench a hand on one knee, and elbow on the other, ala Picasso’s portrait.)

“You are one Alice, only one, always one. Having one who is you and you always nagging, nagging always and only me, I, Alice—not Pablo, not Anna, not Ernest—but I and I alone will send you Alice—not Pablo, not Anna, not Ernest, you you and you only, I will send you not to the druggist, not to the bookstore, not to the WC but Alice always and only you I will send to pow! Zoom! to the moon Alice! To the Mooooonn!!!!”

Brilliant! They send me a form letter for god’s sake. Not even the courtesy of a personal reply. Leaving genius to fend for itself with five miserable dollars in its pocket.

How is it that some twenty one year old white boy who’s never even heard of the Lost Generation is making the yes and no decisions that could ruin or save my life! (Galloway, Lardo, ts., l993, 25-27)

A certain alphabet network—which shall remain nameless—was offered a chance in a lifetime opportunity to produce my proposed teleplay—an intellectual revision of The Honeymooners in which Ralph and Alice Cramden are replaced by Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Foolishly I offered those puffbrains in charge of programming not just a host at the series but a shot at me! Who better for the role of Gertrude Stein than moi! No, judge for yourselves, judge for yourselves.

(SHE rummages for the script, pulls out a huge mother of a script titled The Honeymooners—The Next Generation.)

This is one of Gertrude’s key monologues. I’ll read you a short excerpt.

(SHE doffs glasses, headband and sits on a bench a hand on one knee, and elbow on the other, ala Picasso’s portrait.)

“You are one Alice, only one, always one. Having one who is you and you always nagging, nagging always and only me, I, Alice—not Pablo, not Anna, not Ernest—but I and I alone will send you Alice—not Pablo, not Anna, not Ernest, you you and you only, I will send you not to the druggist, not to the bookstore, not to the WC but Alice always and only you I will send to pow! Zoom! to the moon Alice! To the Mooooonn!!!!”

Brilliant! They send me a form letter for god’s sake. Not even the courtesy of a personal reply. Leaving genius to fend for itself with five miserable dollars in its pocket.

How is it that some twenty one year old white boy who’s never even heard of the Lost Generation is making the yes and no decisions that could ruin or save my life! (Galloway, Lardo, ts., l993, 25-27)

Undeniably, this comic bit was just too rich and funny and complicated to jettison solely because a British audience wouldn’t be familiar with a classic American television show. Like so much of the language in Lardo Weeping, this section works in perfect tandem, liberal feminism and postmodern feminism cycling on the same axle. Realistically, the liberal feminist Dinah questions the privileged status of the “twenty one year old white boy” who is determining America’s programming decisions. And realistically, we cannot help but empathize with Dinah’s unappreciated genius and understand why her impoverished existence is both unjustified and justified. Yet we also can’t deny the postmodern feminist turn either, because by expertly conflating a working class, heterosexual fictional couple on a classic American television show with that of an artistic, expatriate, privileged lesbian couple’s relationship in a Paris salon, Galloway/Dinah throws the similarities between the two couples in comic yet pointed relief. Moreover, the multilayered body of Dinah becomes more complicated: the writer/performer Terry Galloway playing the obese, financially-strapped Dinah LaFarge whose body shifts into Picasso’s portrait of Gertrude Stein before metamorphosing into the signature phrase and gesture of Jackie Gleason.

Yet in anticipating our month-long run in London, Terry and I had to ask ourselves--what is lost if the British audience only “gets” the high art, European allusions? Our solution for that particular run was to secure a PAL copy (British equivalent of a VHS tape) of a five-minute loop of The Honeymooners that was continuously played on Dinah LaFarge’s old black and white television during the preshow. It may not have been the perfect solution, but it was our feminist dramaturgical attempt to bridge the cultural American text / British audience divide.

My second extended example illustrates the way historical circumstances in America in 2002 influenced the feminist reading of Lardo Weeping. The University of Texas in conjunction with the Rude Mechanicals had scheduled a series in Austin entitled: "Throws Like a Girl": Nations’ Most Influential and Provocative Female Performance Artists: Marty Pottenger, Peggy Shaw, Terry Galloway. Wanting to live up to the billing, Galloway and I asked a close friend and fellow feminist, Dona Milinkovich, to help us prepare for the scheduled Austin production by first scrutinizing all the different drafts of Lardo Weeping. As a result, some comic/tragic bits appearing in early drafts, omitted in later drafts, were re-inserted. For example, because this Lardo Weeping production would be the first one done during George W. Bush’s presidency, one of Dinah’s comic routines with a strong environmental moral was reinserted because of its renewed relevance.

That the reading of Dinah LaFarge’s body changes with historical circumstance can be illustrated even more specifically by recounting the audience reaction to one moment in Dinah’s climactic striptease in the 2002 Austin, Texas production. In this moment, Dinah LaFarge strips off her right arm only to be startled to discover the American flag: “Arrah. Good God. Now what have I revealed about myself? That I wear my patriotism on my sleeve? That I believe in the right to bear arms?” (Galloway, Lardo, 27). This visual image of the flag and Dinah’s lines had consistently for over a decade been greeted with laughter. Yet on opening night, on March 21, 2002, (six months after September llth and five months after the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan ) the Austin audience responded with a “HUGE COLLECTIVE GROAN.” (Nudd, “2002 Austin”). It was an unexpected, yet expected reaction. Unexpected, of course, because it differed so dramatically from the audience response to the same theatrical moment that we had witnessed fifty times previously; expected because the audience’s collective groan mirrored our own political views of the time, for the groan was indeed a “reaction to the current war, a reaction to the onslaught of flags and patriotic fervor” that was then consuming America (Nudd, “2002 Austin”).

As I reread my dramaturgical notes from the spring 2002 Austin production, it’s clear that our l990s postmodern heroine, Dinah LaFarge, was again being critically analyzed by feminists, this time ones in our new century. For me, the collective audience groan reminded us of feminism’s responsibility to the anti-war movement. Feedback from post-show discussions with feminists also asked—What is Dinah’s sexuality? What can Disability Studies teach us about Dinah LaFarge? Should Dinah’s comic impersonation of the whore, Bubbles LaRue, be made more complicated?

As I reread my dramaturgical notes from the spring 2002 Austin production, it’s clear that our l990s postmodern heroine, Dinah LaFarge, was again being critically analyzed by feminists, this time ones in our new century. For me, the collective audience groan reminded us of feminism’s responsibility to the anti-war movement. Feedback from post-show discussions with feminists also asked—What is Dinah’s sexuality? What can Disability Studies teach us about Dinah LaFarge? Should Dinah’s comic impersonation of the whore, Bubbles LaRue, be made more complicated?

My notes from Austin also reveal that Dinah’s body (the fat suit costume) was looking a “little tattered,” that “duct tape repairs” were made for the production and that Terry used fabric paint to give the raw body, the undersuit, “more of an edge.” (Nudd, “2002 Austin”). This summer, in anticipation of a spring 2007 production of Lardo Weeping here in Tallahassee, Florida, one of our costume designers, M.L. Baker, is busy making the requisite physical repairs to the costume as well as adding an additional visual pun we want to incorporate into the body.

Without a doubt the comment that resonated the most in the Texas run came from a graduate student at the University of Texas [8]. In one of our guest artist classroom visits, I mentioned that I had been working on an essay that would recount the myriad ways that feminists had served as dramaturgs through the development of Lardo Weeping, I admitted that the essay had been on my computer for over a decade and I had not ever submitted it for publication, much like Galloway had never tried to get the play itself published, because both of us still felt somehow the work, Lardo Weeping, wasn’t finished yet. The graduate student astutely noted that perhaps that was simply because our own physical bodies, as well as feminists’ complicated views of our own bodies, are forever changing (Nudd, “2002 Austin”).

Resisting the Curtain Call

People who do not consider themselves artists often are curious as to where artists get their ideas. At a lecture in Tallahassee, Joyce Carol Oates once said that “all art is autobiographical, it’s just differently coded.” As noted at the onset of this essay, Galloway’s determination to create a female Falstaff has an autobiographical catalyst—her experience, at the age of 21, of playing Shakespeare’s Falstaff in Henry IV, Part I. Yet there’s another way that Lardo Weeping could be considered a “differently coded” version of Galloway’s life. Dinah LaFarge’s extra large (and complicated) body is also a not so thinly-disguised stage metaphor which allows Galloway to explore her own, for the most part invisible, disability. Dinah’s body exemplifies the ways Galloway’s own deafness makes her “feel”: “Body as outcast. Body as ridiculous. Body as scorned. Body as useless.” (Interview.) In translating that “Body” into a female Falstaff figure, Dinah La Farge triumphs, Galloway triumphs, the differently-abled body triumphs, feminists triumph, public intellectuals triumph.

Lardo Weeping also can be considered a “differently coded” version of two decades of Galloway’s and my continuing conversations among feminists—theorists; graduate students in our women’s studies, performance studies or guest artist classes; insightful readers of the text(s); spectators; members of our technical crew. Lardo Weeping could have been a facile show, a series of fat jokes and poems connected by a mostly improvised narrative. But feminists, ourselves included, kept asking the difficult questions: why fat? why poor? why in exile? why an intellectual? why not sexual? why American? Because of the feminist insistence on a deeper personal and cultural analysis, Dinah LaFarge became something much more than an “entertainment.” Lardo Weeping became an artful examination of fat, of costume, of poetry, of popular culture, of politics, of feminism, or self, of society, of will and circumstance.

In writing on dramaturgy, Geoffrey Proehl notes:

To many audience members the dramaturgy of the play will itself be as invisible as its sometimes silent cousin, the dramaturge. And yet, it is this invisibility—this dramaturgy that is felt but not quite seen—that enables the presence before us of so many palpable wonders and terrors. (29)

Lardo’s invisible collaborative process reflects our continuous conversation among feminists (the ones we talked to and the ones we read) about what it means to be Dinah LaFarge, what it means to be an obese white woman in American society, what it means to be a human being who can live in contradiction. Lardo Weeping becomes a philosophical meditation on the nature of being itself. A meditation that continues.

Notes

1. I would like to acknowledge Terry Galloway, the anonymous reviewers, the editors, and members of my research group (Stacy Wolf, Jerrilyn McGregory, Carol Batker, Carrie Sandahl, and Delia Poey) who have freely offered their insights at different times during the lengthy development of this manuscript. I would also like to thank Beatrice Queral who has served as our official photographer, not only for Lardo Weeping, but for virtually every other theatrical or video production Galloway and I have done for the last twenty years. And I would also like to acknowledge Donna Betts for assistance with scanning the photographs that accompany this essay; and Diane Wilkins, who shot and edited the video excerpt, “Taking It All Off” from Lardo Weeping that accompanies this essay and who also has expertly shot, directed and documented a number of our theatrical projects over the last decade. The script for Lardo Weeping can be found at North American Women's Drama

2. For my dramaturgical duties differ as to whether they are in service of an original one person, touring professional show; or a community-based theatre production like our A (Moveable) Midsummer Night’s Dream, or a controversial cabaret skit, such as a recent ten minute, reality tv, game show parody called “Disability Factor.”

3. In a recent email exchange, I asked Gayle Austin, “who do you think has most taken up your challenge in terms of answering these questions in the last eight years?” (Nudd, “quick”). She replied, “my quick answer would be ‘no one’"(Austin, “quick”).

4. Throughout this essay, Dinah’s size and other women who share Dinah’s size are depicted using words that resonate in very different ways (large, plus-size, obese, big, huge, fat, overweight, 56-54-65, grotesque, full-figured.) Among these choices “plus-size” and “full-figured” perhaps have more positive connotations in American society than the others. But since all the women I know, as well as Dinah LaFarge, use a range of adjectives to describe women who surpass the medically recommended Body Mass Index, I do so too in this essay.

5. In focusing on the ways that the larger feminist community served as invisible dramaturges during the development of Lardo Weeping, I am of course looking at one specific angle in the creative process. Certainly, fellow artists, writers, community theatre patrons, family members—had an influence on Lardo’s structure, sight gags, set pieces, language. And, of course, there were infinitely more suggestions that we ignored than those we seriously contemplated.

6. Only selective performances are highlighted in the essay. For a complete listing of Lardo Weeping in performance, print and video, see "Lardo Weeping: A Bibliography of Theatre Productions, Reviews, Publications and Video Distribution."

7. Feminist theorists influenced our thinking about this character throughout the development of the show. While this section of the essay cites theorists I read one particular summer, my early essay published in TPQ cites many other feminist theorists who clearly influenced us: Judith Butler, Sue-Ellen Case, Teresa de Lauretis, Elin Diamond, Susan Faludi, Judith Fetterley, Jeanie Forte, Jane Gaines, Germaine Greer, Nancy Harstock, bell hooks, Ann Kaplan, Kate Millett, Alicia Ostrirker, Catherine Schuler, Patrocinio Schweickhart, Elaine Showalter, Barbara Smith, and Bonnie Zimmerman (Nudd, “Postmodern”).

8. I would like to cite the graduate student by name, but unfortunately, I did not identify her specifically in my notes.

Works Cited

Austin, Gayle. ”Re: quick feminist dramaturgy answer for you.” Email to Donna Marie Nudd. 19 June 2006.

Austin, Gayle. “Feminism and Dramaturgy: Musings on Multiple Meanings.” Contemporary Issues in Dramaturgy. Ed. Sharon L. Sullivan. Spec. Issue of Journal of Dramatic Theory and Criticism 13.1 (1998): 121-24.