Unless noted otherwise, all works in this issue are licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License..

Nicolas Whybrow

This performance represents a form of reciprocation of a particular artwork whose functioning was dependent precisely on the responses of a viewing or participating public. However, where members of that broad-based public may have been content simply to play their small part, my response has attempted to produce (or perhaps that should be post-produce) my own artwork, which I present here as a form of ‘performance on the page’. I will introduce the original artwork in some detail first and then go on to my artwork-as-response as a form of postscript, whereby I should say that the latter probably raises more questions and opens more possibilities than it may seek to address with any rigour. I would defend this as a tactic since it replicates the form not only of the artist’s original work but the popular one that the artist concerned adopts, namely that of postcards.

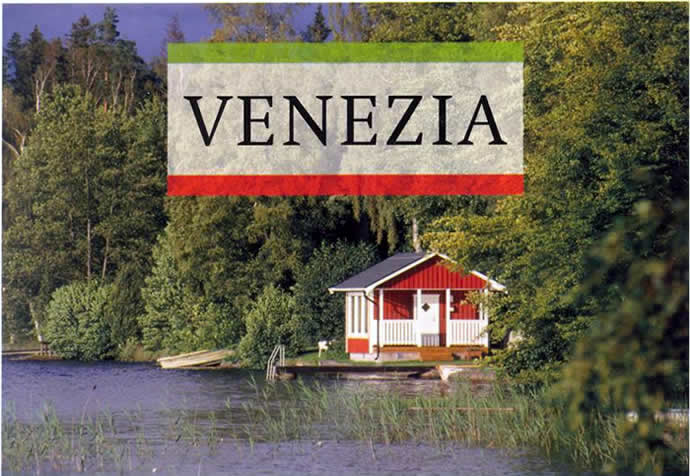

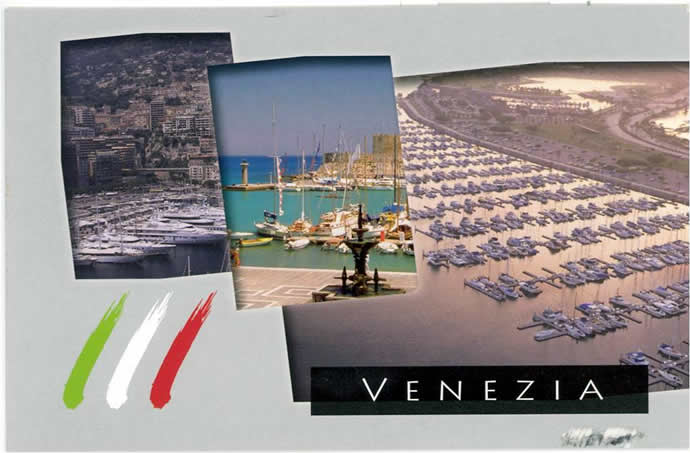

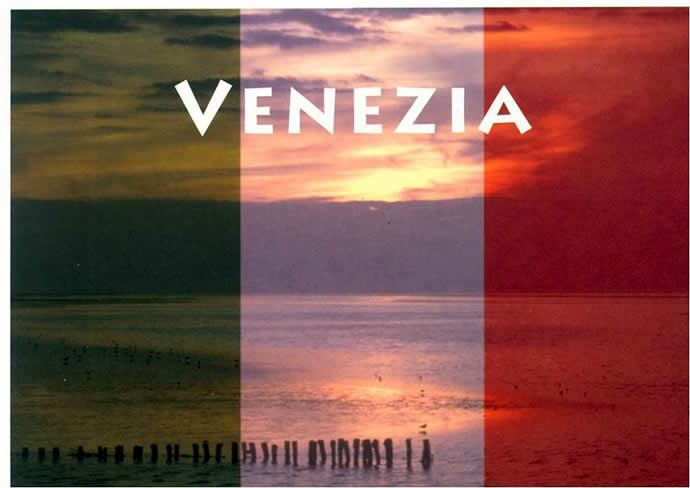

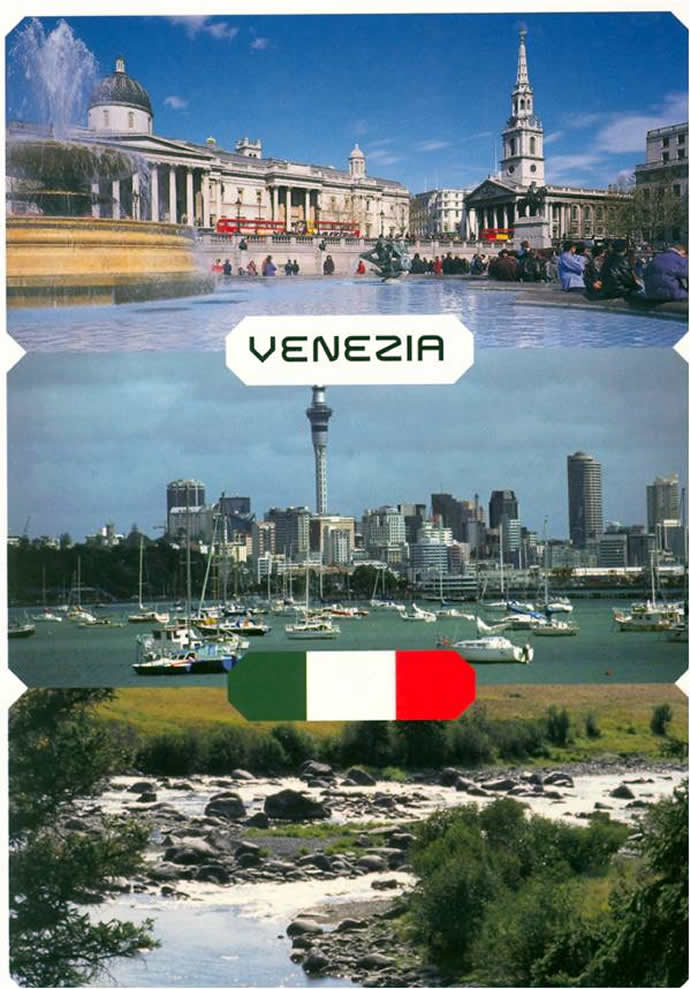

The Polish artist Aleksandra Mir’s VENEZIA (all places contain all others) for the 2009 Venice Art Biennale relied on visitors to activate the artwork. One hundred different ‘Venice postcards’ – each one printed up 10,000 times, amounting to a million in total – were dispensed for free in the hope that Biennale visitors would send them out into the ‘whole wide world’ (a ‘real-life’ world wide web). Emblazoned on all the postcards is the sign ‘Venezia’, often inflected by the green/white/red national colours, or some equivalent symbol, of ‘Italia’. Thus, the ‘myth of Venice’ appears to be claimed as a key part of Italian identity and, perhaps to a lesser extent given the city’s renowned and protracted sense of independence, vice versa. The engagement with questions of nationhood is placed in further perspective by the Biennale’s traditional emphasis on creating a form of artistic Olympiad, with ‘competing nations’ being housed in their own pavilions in the main Giardini site. Like the art of the Biennale, then, the postcard often seems to perform the function of representing national place(s).

At second glance, though, the images turn out not to be of Venice at all, but of other ‘watery places’, sometimes even composites of several ‘watery places’ in quite distinct countries. Not only is it suggested that Venice ‘contains all other places’ but that all other places contain Venice. The act of sending a million postcards – initially stored in tightly-packed blocks on palettes or contained neatly in typical postcard racks – out into the global-postal ether, from a ‘watery place’ to ‘a million other places’ arguably replicates the ice melting, evaporating, cloud-gathering, rain-falling, seeping-into-the-earth climatic cycle of H2O. But the ‘not-Venice-ness’ of Mir’s postcards also proposes a certain triangulation: what might be called a ‘topological’ tension between the here (the text ‘Venezia’), the there (the ‘not-Venezia’ of the image) and the elsewhere of the postcards’ destinations. The not-Venice aspect has a precursor perhaps in Magritte, but where his famous pipe was ‘not’ because it was an image or representation of a pipe, Mir’s not-Venice is actually somewhere else, linked only by virtue of its arbitrary ‘wateriness’. So, water, that natural commodity, is here that which is ‘in common’.

And water is, of course, what Venice itself is all about: living with the immediate reality, but also metaphor, of water. It frequently falls from above and, as the tides come in, it rises from below, flooding the city and threatening its sinking. Historically the city-state’s singular organisation around water guaranteed its power as an unassailable hub, repelling interlopers, sending its trading forces out into the world and drawing them back into the secure fold of the republic, enriched. An ebb and flow of wealth creation. Now the tides have not only turned but been overturned: Venice’s citizenry, at least the small portion that resides in the only-too-familiar centro storico (as it is now becoming known, not without controversy—identifying the six ‘sestier’ (areas) of Venice as a ‘historical centre’ is a recent move by the powers that be that is indicative of the desire to transform the city wholly into a place for tourists as opposed to residents.), stays put these days and lies in wait for the opportunity to create wealth, as the great wash of visitors drifts in and out (often, like the tides, within the course of a single day).

My ‘performed’ response takes up Mir’s challenge to write and send out postcards. Perhaps it ends up giving the artist more than she bargained for by being very specific about its textual content and by being mounted as a collection of ten (mathematically representing 0.001% of the artwork as a whole). Ten postcards were dispatched by me, the writer, on the last day of a short visit to Venice in November 2009 – just as the Biennale was drawing to a close – to my home town of Coventry, UK. Remarkably they all arrived, in drips and drops, within four days. They are from a certain ‘N’ to ‘another N’, suggesting an indeterminate me-in-Venice to me-in-Coventry, the former being not-me or only-temporarily-me (since I am in a place that is for me ‘elsewhere’), whilst the latter is not-me, too (since I am not, at the time of writing the cards, there but in Venice, which is for me elsewhere). Thus, as I received the postcards and began piecing them together in narrative order, they formed what might be called a ‘small corner of Coventry that is forever not-Venice’ or forever a ‘silencing of Venice’.

The text of the postcards attempt to convey a sense of certain Biennale artworks – specifically those by Bruce Nauman (Topological Gardens), Roman Ondák (Loop), Mike Bouchet (Watershed) and Steve McQueen (Giardini) – all of which engage with the Biennale from the twin points of view of Venice’s cityscape and a problematised ‘idea of nationhood’, as well as with the twin concepts of loops and gardens. So, where the image on the front of any one postcard is clearly not of Venice, the text on the back is about the place, about ‘ways of approaching’ the place called Venice and the space of its Biennale. In that sense I am utilizing Mir’s artwork as a means to negotiate and map an experience of the Biennale as it relates to the city of Venice. But it also entertains the possibility of ‘making new topological worlds’. ‘Making Worlds’ was the formal title of the Biennale in 2009 and the concept of topology, with which Nauman engages specifically through the three sites of his exhibition – which took his work beyond the Giardini and out to locations in the city – proposes a ‘poking into these seemingly discrete and separate territories’ [See Carlos Basualdo in 53rd Venice Biennale catalogue, Making Worlds: Participating Countries, Collateral Events, Venice: Marsilio, p.148]. The logic of these multiplicative and inverted ‘subsets’, relating to the ‘representative art of a nation’ as embodied by the US pavilion, points, via their displacement, to the sheer impossibility of representing that nation. Moreover, like Mir’s artwork, the concept of topology ‘provides a framework in which the audience can relate the experiences of and encounters with Nauman’s art to traversing and negotiating the city’ [See US pavilion exhibition brochure, Bruce Nauman: Topological Gardens, 2009, p.2].

Postcards naturally link to tourism and, in Venice’s case, the millions of tourists that visit annually. Mir is clearly fascinated by the continuing prevalence and popularity of postcards when they are, arguably, an anachronistic relic in an age of electronic image transfer. Why does the postcard still thrive in a place like Venice where every visitor comes armed with the means to record and send images and messages around the world in an instant? Perhaps it is to do with that mythical sense of the city’s ‘historical quaintness’, the sentiments of romance and nostalgia it provokes. To the visitor the ‘ancient ritual’ of sending postcards somehow seems appropriate in a place that so powerfully evokes ‘a former age’. But, of course, postcards are not limited to Venice. They are generally one of the currencies of expression or identification available to the tourist – pretty well exclusively. (In other words, who else are they supposed to be for?) The postcard functions, then, as a celebratory, in-the-moment certification for the tourist of ‘being away-ness’ – confirmation of the fact of being and/or having been away (‘send us a postcard when you get there’) – and of conquest: the ‘been there, done that’ syndrome of hackneyed vistas and iconic monuments. It can exist alongside the emergent ubiquity of personal, instantaneous image and text-making because it implies perhaps an act of local sanctioning: you buy (into) this image and the city is pleased to confirm your presence here.

Tourist snapshots – by comparison ‘stolen images’ – are also highly prevalent, of course: everyone in this age of cheap and easy digital photography seems to be armed with the means to take pictures. And Venice is such – ‘picturesque’ is the word, I suppose – that the shots are extraordinarily obvious and available: ‘there for the taking’. Similarly, Venice scenes – right down to those of ‘other’ or ‘little known’ Venice – are pre-formed, pre-set, pre-seen, pre-judged. Whether postcard or snapshot, Venice is always already the image or idea of Venice; there is only ever a narrative of Venice, which takes you away from Venice. It is an expression of absence or loss, masquerading, though, as presence. To go back to Magritte: his take on Venice might plausibly have been a postcard image of the Grand Canal with the title This is Not Venice. What, then, would Aleksandra Mir’s rewriting of that imagined image be? Well, where Magritte writes a statement below the image – and the former produces the conundrum of the artwork – Mir lets the image produce the question mark in the viewer’s mind, partly because we do not as a rule recognize where the place depicted is, just that it’s evidently not Venice. In other words, image does not fit descriptor. It is the ‘wrong place’. But, as that, as a ‘disjunctive space’, it has the effect perhaps of drawing attention to the instability or ‘wrongness’ of the place that we take to be Venice.

So, Mir’s artwork represents a form of displacement, but for whom? The writer? The recipient? Whosoever may come across the postcard? Noticeable is that the postcards subscribe to, even go out of their way to highlight, the features of the clichéd design aesthetic of the tourist postcard. And many of the alternative images are of other tourist sites (even if you don’t recognise them specifically) or tourist activities. Some postcards actually mix up places; Trafalgar Square, for instance, is mixed in with sites in other countries entirely. The postcards also emphasise, as I have suggested, national identity: Venezia as a key part of Italia. But what predominates is the postcard – in its various classic configurations, its graphic stereotypes – as an artefact of the tourist experience. In that regard, the place that is evoked is actually immaterial. The important thing is the emblematic sign that is VENEZIA, nationally inflected not so much because Italian identity itself matters here, but because doing so invokes an association with romantic escape. Arguably, then, as communication devices, postcards have far less to do with representing the place-ness of specific places than simply a schematic sense of ‘exotic away-ness’. The place itself is ‘neither here nor there’, ‘all places to all others’; the messages written on the back are banal, as much so as the present-day ‘I’m on the train’ equivalent repeatedly heard in cell phone culture. That other essential feature of the postcard, the signature ‘wish you were here’, appears to signify little more than ‘here, doing the tourist thing with me’. What matters is conveying an impression of ‘time out’ or ‘time away’, beyond the shared humdrum of everyday existence. But, whilst the phrase in question may well be expressing the desire for the addressee to ‘be here witnessing me doing this fun tourist thing’, subconsciously the writer is probably glad that those from ‘back home’ are precisely ‘not here’ otherwise the secure myth of the ‘exotic’ may well be threatened. In the case of my response to Mir’s postcards they are wished away instead to a watery not-Venice.

Postcards Sent to Coventry

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

Appendix: Postcard Texts

1.

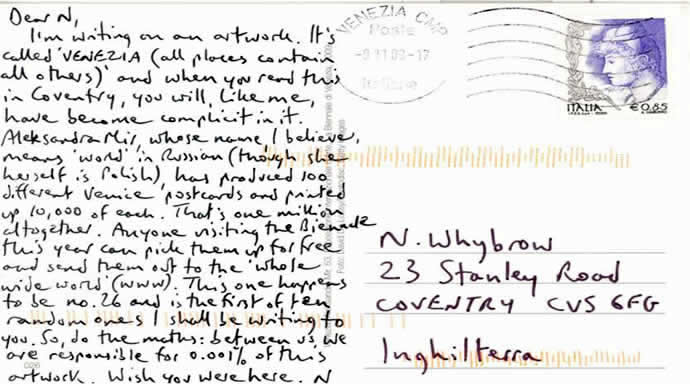

Dear N,

I’m writing on an artwork. It’s called ‘VENEZIA (all places contain all others)’ and when you read this in Coventry, you will, like me, have become complicit in it. Aleksandra Mir, whose surname I believe means ‘world’ in Russian (though she herself is Polish), has produced 100 different Venice postcards and printed up 10,000 of each. That’s one million altogether. Anyone visiting the Biennale this year can pick them up for free and send them out to the ‘whole wide world’ (www). This one happens to be no.26 and is the first of ten random ones I shall be writing to you. So, do the maths: between us we are responsible for 0.001% of this artwork.

Wish you were here,

N

2.

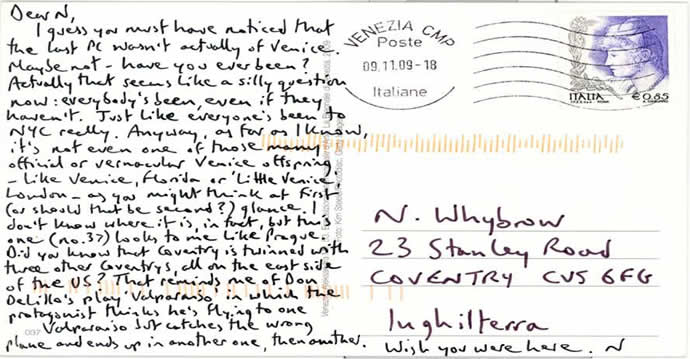

Dear N,

I guess you must have noticed that the last postcard wasn’t actually of Venice. Maybe not – have you ever been? Actually, that seems like a silly question now: everybody’s been, even if they haven’t. Just like everyone’s been to New York City really. Anyway, as far as I know it’s not even one of those many official or vernacular Venice offspring – like Venice, Florida or ‘Little Venice’ in London – as you might think at first (or should that be second?) glance. I don’t know where it is, in fact, but this one (no.37) looks to me like Prague. Did you know that Coventry is twinned with three other Coventrys, all on the east side of the US? That reminds me of Don DeLillo’s play Valparaiso, in which the protagonist thinks he’s flying to one Valparaiso but catches the wrong plane and ends up in another one, and then another.

Wish you were here,

N

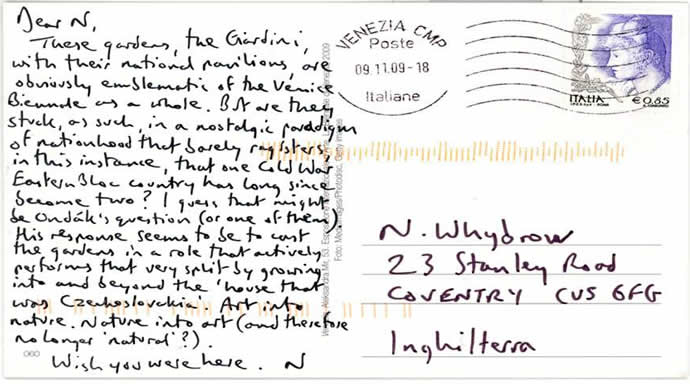

3.

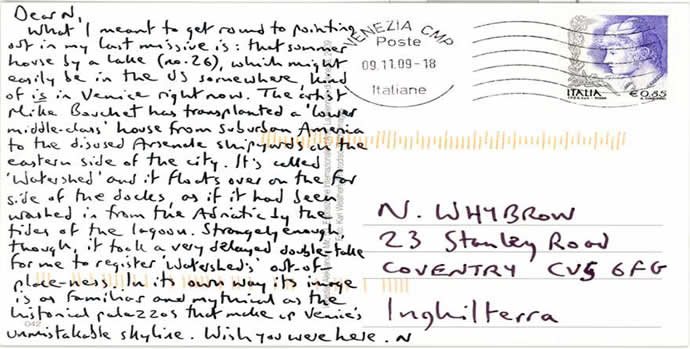

Dear N,

What I meant to get round to pointing out in my previous missive is: that summer house by a lake (no.26), which might easily be in the US somewhere, kind of is in Venice right now. The artist Mike Bouchet has transplanted a ‘lower-middle-class’ house from suburban America to the disused Arsenale shipyards on the eastern side of the city. It’s called ‘Watershed’ and it floats over on the far side of the docks, as if it had been washed in from the Adriatic by the tides of the lagoon. Strangely enough, though, it took a very delayed double-take for me to register ‘Watershed’s’ out-of-place-ness. In its own way its image is as familiar and mythical as the historical palazzos that make up Venice’s unmistakable skyline.

Wish you were here,

N

4.

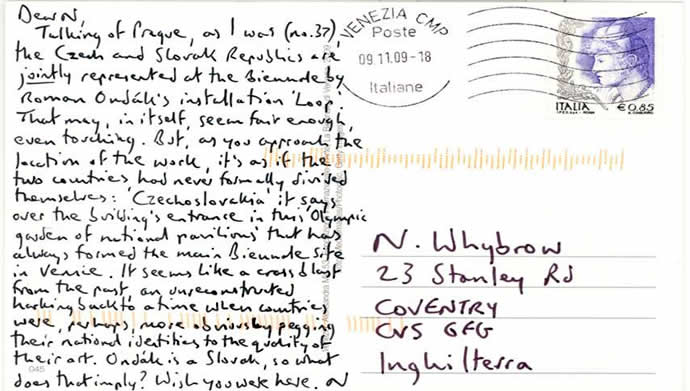

Dear N,

Talking of Prague, as I was (no.37), the Czech and Slovak Republics are jointly represented at the Biennale by Roman Ondák’s installation ‘Loop’. That may, in itself, seem fair enough, even touching. But, as you approach the location of the installation, it’s as if the two countries had never formally divided themselves: ‘Czechoslovakia’ it says over the building’s entrance in this ‘Olympic garden of national pavilions’ that has always formed the main Biennale site in Venice. It seems like a crass blast from the past, an unreconstructed harking back to a time when countries were, perhaps, more obviously pegging their national identities to the quality of their art. Ondák is Slovak, so what does that imply?

Wish you were here,

N

5.

Dear N,

When I entered the pavilion housing ‘Loop’, my first impulse was to think I had wandered into the greenhouse of some botanical gardens. Finding myself alone, it felt like a pleasant interlude amidst the sheer pizazz and challenge of ‘all that art’. A path led me through various tall plants and foliage and out the other side. Huh? The Giardini internalised or interiorised? Which came first, the plant life or the building? And is the inside of the building outside now, or the plant life inside? The domestication of nature or the naturing of domesticity? There’s the loop.

Wish you were here,

N

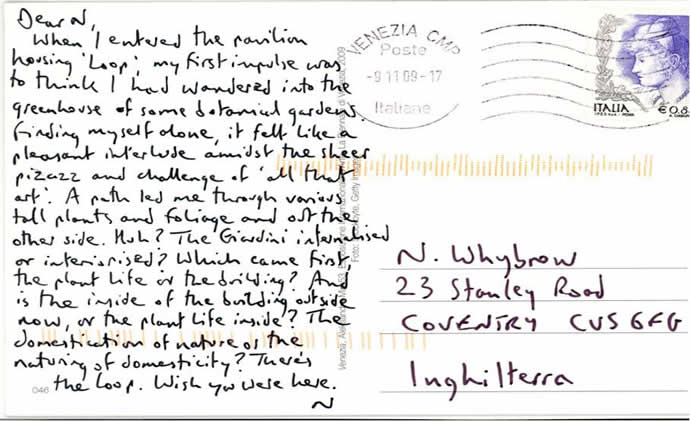

6.

Dear N,

These public gardens, the Giardini, with their national pavilions, are obviously emblematic of the Venice Biennale as a whole. But are they stuck, as such, in a nostalgic paradigm of nationhood that barely registers, in this instance, that one ‘Cold War Eastern bloc country’ has long since become two? I guess that might be Ondák’s question (or one of them). His response seems to be to cast the gardens in a role that actively performs that very split by growing into and beyond the ‘house that was Czechoslovakia’. Art into nature. Nature into art (and therefore no longer ‘natural’?).

Wish you were here,

N

7.

Dear N,

From afar the neo-classical US pavilion, positioned bang in the middle of the Giardini site, screams for attention. Bruce Nauman’s gaudy ‘neon signs’, flashing up on its outside walls, are ‘very Times Square’, ‘very Vegas’. As you edge closer, though, the words that make up these supposed ‘vices and virtues’ begin to write over one another: palimpsests that produce disjunctive combinations, mystic (un)truths – arguing with one another, like the neon talking heads and gesticulating hands inside the pavilion.

Wish you were here,

N

8.

Dear N,

Like Mir’s artwork, Nauman’s ‘Topological Gardens’ proposes a migration beyond the spatial confines of the traditional Biennale site, this ‘neighbourhood of national pavilions’. Thematic pairings of headwords encapsulating the artist’s work since the 1960s figuratively thread their way across Venice to two separate university sites: one a Gothic palazzo on the Grand Canal, the other a former convent not far from the Papadopoli Gardens. This is a retrospective, but, more compellingly, it is dependent structurally on both the spectator/pedestrian’s negotiation of the space of the contemporary city and the changing nature of the city’s spaces in time.

Wish you were here,

N

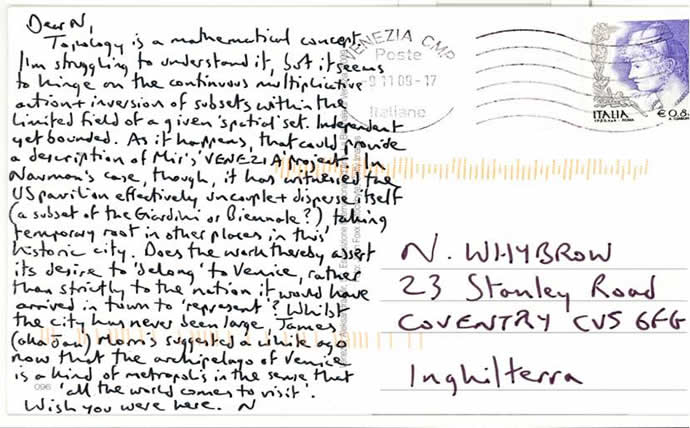

9.

Dear N,

Topology is a mathematical concept. I’m struggling to understand it, but it seems to hinge on the continuous multiplicative action and inversion of subsets within the limited field of a given ‘spatial’ set. Independent yet bounded. As it happens, that could provide a description of Mir’s ‘VENEZIA’ project. In Nauman’s case, though, it has witnessed the US pavilion effectively uncouple and disperse itself (a subset of the Giardini or Biennale?), taking temporary root in other places in this historic city. Does the work thereby assert its desire to ‘belong’ to Venice, rather than strictly to the nation it would have arrived in town to ‘represent’? Whilst the city has never been large, James (aka Jan) Morris suggested a while ago now that the archipelago of Venice is a kind of metropolis in the sense that ‘all the world comes to visit’.

Wish you were here,

N

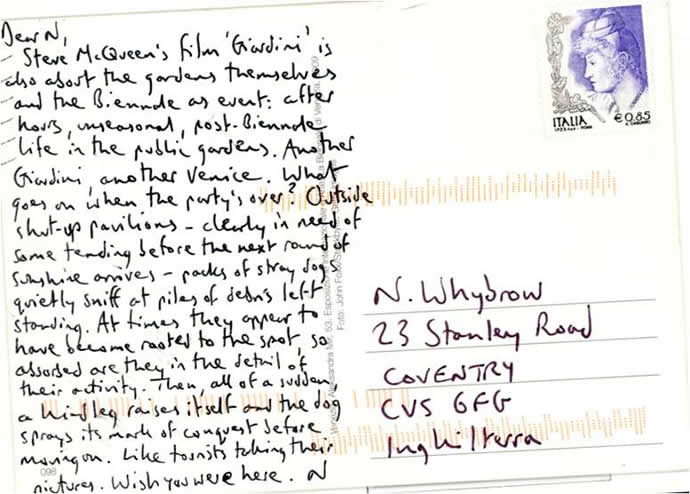

10.

Dear N,

Steve McQueen’s film ‘Giardini’ is also about the gardens themselves and the Biennale as event: after hours, unseasonal, post-Biennale life in the public gardens. Another Giardini, another Venice. What goes on when the party’s over? Outside shut-up pavilions – clearly in need of some tending before the next round of sunshine arrives – packs of stray dogs quietly sniff at piles of debris left standing. At times they appear to have become rooted to the spot, so absorbed are they in the detail of their activity. Then, all of a sudden, a hind-leg raises itself and the dog sprays its mark of conquest before moving on. Like tourists taking their pictures.

Wish you were here,

N