13 ways to kill a mockingbird

![My conversation with To Kill a Mockingbird (TKM) has been complicated from the onset by nostalgia. I do not like to be especially autoperformative—although it all always really amounts to that, you just don’t always reveal how—but I will disclose that part of my sentimental attachment to TKM has to do with Atticus Finch’s resemblance to my father, especially the way Gregory Peck carries himself in the film, and of course all the projecting the film and novel themselves encourage you to do if you are the female child of a slightly old-fashioned, good-hearted, articulate and somewhat eccentric father and you are drawn to his world. Besides giving the kinds of temperate and tolerant advice Atticus gives to Scout, my father wrote scripts for such forgotten documentary classics as the series “Science in the Seventies”; he co-wrote a book on educational telecommunication and wrote his thesis comparing British and American television broadcasting for a masters degree in Communication. I did NOT intend to follow in his footsteps or anything like that—I was in theatre, working with imaginative literature, but one day I woke up in a Communication Studies department in Baton Rouge with a mini DV camera in my hand, nut having fallen surprisingly not far from tree. “Stand up, Jean Louise, your father’s passing.”

There’s also the problem of the memory of reading the book and falling head over heels in love with Scout, wanting to be her, to speak like her, to dress in overalls like hers, to climb trees and beat up neighborhood boys like her.

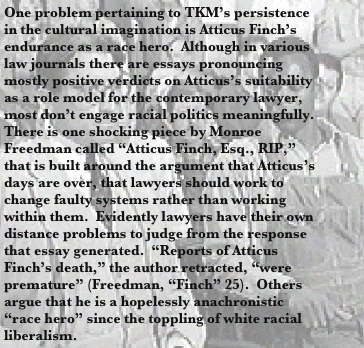

I am hardly alone. The Library of Congress collaborated with the Book-of-the-Month Club[2] on one of those millennial fever surveys that asked Americans, on the eve of the 21st century, what book had made the most difference in their lives. The results: #1, the Bible: #2, TKM. The survey did not ask “What is your favorite book?” or “What is the most important book?” but “What book made the most difference in your life?” You see, it’s a question that has the collapse of distance built into it. I can’t prove this, but in my mind, this effect, the power to affect, has something to do with the relative dearth of critical material published on TKM—except if you read law journals, where there is so much of it that it could crush you. In the law journals, they tend to talk about Atticus Finch as if he were a real person.](4_files/shapeimage_3.png)

At any rate, thinking about all of these issues at least gave me some critical context for my obsessions with Atticus and Scout, but that didn’t make the problem go away. But here comes the “eureka!” moment: it is far more interesting, honest, and—I suspect—theoretically challenging and engaging not to erase or bracket out this problem, but to confront it head on, or to stage it. And luckily, Wallace Stevens had been in my title all along, and ultimately, he, Terry Galloway, Scout, Atticus, my dad, Martin Arnold, Bill Viola, the Monroeville Alabama Heritage Museum, LSU’s Laboratory for the Creative Arts and Technology, and a whole bunch of wonderful students and colleagues finally helped me to see what I wanted to do with this Big American Story.

I was sitting in one of those lobby bar things in Miami Beach at the National Communication Association conference one November trying to explain the project I was contemplating to performance artist Terry Galloway, who had coincidentally just reread TKM, and although she helped me to sort it out, she had it worse than I did over that book. And then a friend of hers joined us, and we discovered we both have Golden Retrievers whom we named Scout, after Harper Lee’s heroine. Months later, when we were taping interviews with readers who were recalling their impressions of TKM, one young man, a graduate student in LSU’s English Department, brought his dog to the interview. Her name was Scout, he explained, after Harper Lee’s heroine[3].

The Hamlet Effect: There are certain characters who, by virtue of metatheatrical, metatextual device or the cultural work of constructing icons, may take on lives of their own (Suchy 15-16). They are not exactly cut loose from their texts, but they exceed them; they proliferate or have currency in culture so much in excess of their texts that they carry, efficiently, a lot of cultural history, baggage, significance. This idea first hit me full force when I read in a biography of Bakhtin how he and his friends used to stage trials of famous literary characters; Bakhtin was evidently very skilled at defending Dostoevsky’s antiheroes like Raskolnikov (Clark and Holquist 50). (Yes, Atticus is going to be put on trial, and yes, that’s precisely where I got the idea.) But back to the Hamlet Effect: The cinema consciously creates such characters, mostly for profit, often for propaganda. Atticus Finch, like Hamlet, is such a hero. To me, one very interesting thing about these kinds of icons is that the significance that congeals around them gives them a weird ability to do what I call “author back,” as Hamlet does to whomever is playing him, in moments like the “To Be or Not To Be” soliloquy where the audience says it along with the performer. “Hamlet” is all prior Hamlets and the cultural contexts that adhere to him.

And I think famous texts, texts that people say have made a difference in their lives, might work in somewhat the same way. They may author our own stories back to us. 13 ways to kill a mockingbird, then, stages a collage of documentary images of those stories with opportunities for both remembered and new spectatorial situations within the field of this text.

We have all sorts of critical tools and training that tell us how to analyze and scrutinize any given text’s reception, themes, cultural context(s), etc. But as I have suggested above, they can’t completely suffice to explain the kinds of emotional responses the text evokes. Witness the response to “Atticus Finch, RIP.” That essay provoked a flood of mail, most of it incensed at the attack on an iconic figure whom many characterize as the essence of ethical behavior. There is not much good, and shockingly little, literary criticism of the text, but it is all over the law journals. Why are the literature scholars relatively silent about it? And why are the lawyers so vocal? What does the figure of Atticus Finch signify to us today? Is he a good man? Do we, or how do we, form such cultural verdicts? What are the duties of a “public citizen” or a pater familias? Does Atticus as white, patriarchal authority figure representing a black man help race relations, or is he guilty of patronage?

In Wallace Stevens’ poem, “13 Ways of Looking at a Blackbird,” the bird in the title “does not have a constant signification but it has a constant function: to act as a focus that brings out qualities in what is put in relation with it” (Sukenick 72, qtd. in LaGuardia 44). As the Stevension “imagination focuses reality's flux, the blackbird focuses the process of the imagination's activity” (LaGuardia 44). In our production, I decided that we would use the text of TKM (text meant here as the whole event of the novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, and the 1963 feature film adapted from it) as our “blackbird,” so to speak. In each of our 13 installations, many of which involved video, projected or on monitors, the text of TKM would not have a constant signification. We were not trying to tell THE story, nor to point to a reading or even readings of it, but to collage many stories and images brought forth through our associations with the text. Instead of “adapting the story” to performance, we would instead strike up and create/perform relations with the text, putting other things/bodies/events in relation with it.

I’m also very interested in Mayella Ewell, who seems to me (and Scout has a dawning awareness of this) a victim of child and class abuse and cultural constructions that amount to another kind of child abuse. Her desire for Tom, misguided before the discovery of it by her abusive father, and subsequently perverted by the entire community, Mayella herself included, is the taboo the community must erase or correct or re-narrate as rape through the public ritual of the trial. I believe that to examine race relations in the text and its contexts and leave Mayella out of it or to dismiss her as the same kind of bigot as the rest is to overlook the complexity of what this story can tell us about ourselves. Scout learns how to behave as a southern woman in this text—she comes of age, in the tradition of the American novel. And as in so many American coming-of-age stories, the coming-of-age process is woven around and through racial and gender constructions. What do we teach children to become? How do we break out, or do we break out, of the cultural roles prescribed for us? “I got somethin’ to say,” she stammers during her testimony, but she doesn’t say what she has got to say.

Every film that photographs live performers is, in a way, a documentary. On a certain day in 1962 on a certain Universal back lot, Gregory Peck held Mary Badham on a porch swing.

Here are some artifacts.

I still wish you’d been here.

image © Universal Pictures

image © Universal Pictures

image © Universal Pictures

image © Universal Pictures

image © Universal Pictures

images © Universal Pictures