Even now I want more; more of what I have carried with me for the last five years whenever I thought about Craig Gingrich-Philbrook’s show, Cups; more of that love story between Craig and his partner, Jonny, that had planted itself in my head in full bloom; more of that feeling that the love between two people transcends dogma and hate, even if dogma and hate take daily negotiation; more of that faith in Gingrich-Philbrook’s words to educate, to calm fears, to make us better people. You see, I want my memory of Craig’s show to be sufficient, not an enigma. I want Craig’s show not to have the subtitle, Sufficiency Enigma 1999. I want to believe that how the show has worked on me over the years was sufficient to the show. But desire, though it may live in the comfort of its own privacy, exposes its vulnerabilities whenever it speaks beyond itself. So, with hesitation I write, not only compelled to explore Cups: Sufficiency Enigma 1999, a show I love both in my memory and in my current encounter, but also to reflect upon the insufficiency of memory and the enigma of its accompanying desires.

The Sufficiency of the Incomplete

He starts the show with a statement of desire: “Even as a boy, I wanted more.” The “more” he wants takes us beyond the young boy on his bike feeling the curve of the road and lying in the lush meadow with his blue dog resting in the crook of his arm, beyond the “sad stories” of his troubled home, beyond his dead brother and estranged father, to a place where he could “just be there,” perhaps with Andy, his boyhood friend, or with someone else who might find him “sufficient, ‘enough.’” He wants to language that desire, to use autobiographical performance as its articulation, despite knowing “we each sit, lonely, isolated, trying to collect ourselves, to compose ourselves after bad dreams in which the love comes to nothing, drinking coffee from our battered cups.” He wants to know what a broken cup can contain.

He tells all of this in front of the curtain after being guided out by the stage manager to the light. It is as if he has been placed in police line-up, asked to step forward, and to confess. And we know he has a story to tell. But before he is willing to share his tale, he informs us that this will not be another of those stories we have come to expect from him. It won’t be all neatly packaged in the aesthetic of repetition, autonomous, separate from our lives; it won’t move forward without fear; it won’t speak as if death has had its say. The curtain opens and he enters the world where the tension between more and enough becomes the enigma of various encounters.

In this world’s first scene, Gingrich-Philbrook rolls up his sleeves, his signature gesture, mirroring the action of a waiter in a New York café. He had gone to the café to write about death, “about having had enough death” in his life, at the urging of his partner, Jonny. He finds himself in the middle of a performance, the waiter’s performance who works the room by pouring coffee into empty cups with the folksy charm of porn star Al Parker and the potency of a newly dominant male zebra that aborts with his highly functional penis all the pregnant zebras so that he can “reinseminate the ‘empty’ zebras with himself.”

The waiter emerges as both oppressor and seducer. As oppressor, he imposes his will upon those present, filling them up, like the zebra, with his performance, erasing their identity as they are cast into the role of the receiver of this presumptive heterosexual display. As seducer, his performance has appeal—its physicality, its efficiency, its sexuality:

As he raises his arms, he pulls that worn t-shirt out of his jeans, up like a curtain. An inch or so of his white boxers show, too, marking all the stages of dress and undress in a small territory: his bare skin, his underclothes, his shirt, and jeans. He’s somewhat tan, and, though this structure of revelation would be enough to momentarily catch my eye until civility led me to turn away, I glimpsed his small yin and yang tattoo, rising like a moon about the edge of those boxes. And, in the final moment of this transformation, the thin trail of hair leading from his navel into his pants caught along the length of forearm, tripping the hair along the edge of me like so many hundred alarms.

Gingrich-Philbrook, despite the attraction, places his hand over his cup, signaling “no more,” and leaves a tip, “wondering if I’ve left him, wondering if I’ve left him enough.”

In a different register, he then asks the audience:

Did you like that story?

Where do you want to look? What do you want to happen?

Are you glad I didn’t act on my attraction toward him? Do you want me to stay faithful to Jonny? Do you think about Jonny? Do you want me to hook up with the waiter, Jonny be damned? Or do you want the waiter for yourself?

Where do you want to look? What do you want to happen?

Are you glad I didn’t act on my attraction toward him? Do you want me to stay faithful to Jonny? Do you think about Jonny? Do you want me to hook up with the waiter, Jonny be damned? Or do you want the waiter for yourself?

And in the asking we are confronted with our first enigma, our first encounter with the issue of sufficiency, of what is enough, of what our cups might contain. The tale is left in questions, projecting alternative endings. It stands as a fiction in this moment’s telling, as a refusal to let death take hold. It is, as Avery Gordon would have it, a story of hauntings and ghosts.

Embedded in the waiter’s story is another tale questioning sufficiency. Gingrich-Philbrook tells of another encounter he experienced when searching on his hands and knees the bottom rack of a poetry section in a New York City book store. An unknown man, head bandaged from a recent operation, appears above him, breathing heavily, his arms extended in anticipation of a hug. This moment takes him back to a dream of his father who returns, like Lazarus, from the dead only to die again through the strength of Gingrich-Philbrook’s welcoming embrace. Remembering his father, Gingrich-Philbrook hugs this bandaged stranger, a hug of gentleness and comfort, a hug of connection. Then, a therapist emerges, pulled forward by a dog on a leash. She says:

Is he bothering you? I’m sorry. He won’t hurt you. He’s recovering from brain surgery. He has a little brain damage. They love everybody when they have brain damage. They love everybody at this stage.

They continue their embrace a moment longer, separate, and the strange man takes Gingrich-Philbrook in “like he knows we’ll never see each other again.” Then, escorted by the therapist, the bandaged man leaves, offering a brief wave once he reaches the door. Gingrich-Philbrook tells us he “never had the dream of my father again.” The hug he gives the bandaged man and the hug he gives his father, the audience is invited to believe, is necessarily sufficient and not enough. Perhaps, brain damage is what is needed.

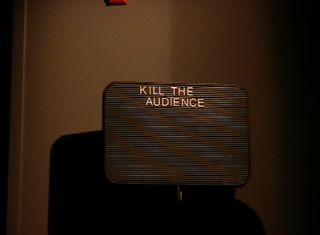

Gingrich-Philbrook’s next story revolves around his decision to move away from New York City and from Jonny for a job in Carbondale, Illinois. As his New York friends express their concern that a gay man won’t be safe in southern Illinois, he remembers the inscription carved in marble in a bathroom stall: “KILL FAGS.” As he relates this, a light comes up on a sign positioned in the aisle to the audience’s right. It reads, “KILL THE AUDIENCE.” He speaks of living a life in fear, sharing his own feelings about sitting in that stall, offering a moment of reflection for Matthew Shepard, bringing forward his own and friends’ stories of narrow escape and stories of those who didn’t, including a southern Illinois man, Michael Miley, who was “killed and beheaded and burned in his car.” The scene ends with Gingrich-Philbrook saying that he has no intention of killing the audience since he isn’t in favor of killings, public or private, but that “none of us are all that safe, really, when you think about it.”

Gingrich-Philbrook’s next story revolves around his decision to move away from New York City and from Jonny for a job in Carbondale, Illinois. As his New York friends express their concern that a gay man won’t be safe in southern Illinois, he remembers the inscription carved in marble in a bathroom stall: “KILL FAGS.” As he relates this, a light comes up on a sign positioned in the aisle to the audience’s right. It reads, “KILL THE AUDIENCE.” He speaks of living a life in fear, sharing his own feelings about sitting in that stall, offering a moment of reflection for Matthew Shepard, bringing forward his own and friends’ stories of narrow escape and stories of those who didn’t, including a southern Illinois man, Michael Miley, who was “killed and beheaded and burned in his car.” The scene ends with Gingrich-Philbrook saying that he has no intention of killing the audience since he isn’t in favor of killings, public or private, but that “none of us are all that safe, really, when you think about it.”

The sign, “KILL THE AUDIENCE,” served to make the audience experience the weight of living under that cultural script for just a few moments and, perhaps not surprising, proved to be a highly contested performance choice. For some, the response to Gingrich-Philbrook’s statement, “I hope that sign wasn’t too much,” was that it was too much. They were, in short, unable to get beyond the audacity of the threat. For others, the sign created an instructive site of implication where the audience could both empathize and acknowledge their own participation in a horrific cultural logic. In a reversal of the previous scenes that locate the sufficiency enigma in the desire to want more, this scene foregrounds the desire to want less, less of those who are not like us. It ultimately asks if killing and, more directly, “killing fags” would be sufficient to satisfy hate.

The final scene returns to love’s sufficiency as Gingrich-Philbrook tells of his move to Carbondale without Jonny. The tender and loving labor of their decision to live apart and of their separation at the train station is juxtaposed to the cultural stereotype that gay relationships are empty, void of genuine feeling. Gingrich-Philbrook then reclaims “empty”—that feeling you have when apart from the one you love. That feeling is exemplified most fully in the story of cups, favorite cups exchanged so that “we could, in a way, still have breakfast together.” Unfortunately, when Jonny comes to visit, the cup breaks, leaving only broken pieces. Gingrich-Philbrook shows the audience a piece of the broken cup. It is half a cup, handle intact, jagged.

I hold onto this piece of broken cup, this handle I couldn’t hold onto when it fell beyond my reach. I keep it in a jar on my windowsill, where it rubs up against other shards of other broken stories. With the rest of them, it catches the sun in the morning, the handle, and the hollow, and the lip of it, warming and cooling with the course of the day.

And though it can no longer hold water to the standards of the material world, it has never, since he picked it up and put it back in my hands, been the slightest, been the slightest bit, been the slightest bit empty.

And though it can no longer hold water to the standards of the material world, it has never, since he picked it up and put it back in my hands, been the slightest, been the slightest bit, been the slightest bit empty.

This broken cup, then, is and is not sufficient, is and is not enough. Its insufficiency, however, seems to slide away against its fullness. It becomes desire’s best, although incomplete, answer to more. This cup tells what a cup can contain. It knows that the shards that can slice open are what keep death at bay.

The Insufficiency of the Complete

My memory’s failure was to let death in, to give closure to the show’s enigmas. Cups, as I remembered it, was a love poem to Jonny, a poem so articulate, so tender, that it rewrote what I understood love to be. It was a display of the power of language to name what slips away, of words to tell passion’s secrets, of metaphors to reveal what may be present in the equation. It was a story of pleasure, a story that gave me pleasure, real and complete as a rose. It was, of course, all that, and, as I hope the section above demonstrates, much more. After revisiting the show, I know I must reluctantly surrender memory’s settled tale, that desire for more of the same, for memory’s tale to be sufficient. Memory, as Cups now instructs me, is not enough.

When Craig moved to Carbondale leaving Jonny in New York, we spent the day together looking for a place for him to live. Craig was most attracted to an old neighborhood with modest homes, many serving as student rentals and many showing their years of hard use. We looked at dwellings with tilting floors, with porches hanging on by the sheer will power of a few nails, with sheds that could become performance spaces, one only big enough for an audience of one. I kept trying to lead Craig to newer neighborhoods, to more upscale places where not long ago there were cornfields. These were houses freshly painted, clean, efficient, ready for occupancy. But Craig would always have me circle back to the old neighborhood. Perhaps, his attraction was to the large oaks shading the streets on that hot August day, the easy access to campus, or the familiarity of the area from his graduate student days. But, more likely, it was to the homes that held their history, the ones that didn’t determine their use, ones where shards of glass rest happily on the windowsill. We never found a house in that neighborhood and settled on a place somewhere between our two desires. When Jonny moved to town, they found a place together in that old neighborhood.

I have always been too easily seduced by the tidy. I live trying to keep everything in its place. And, when the dust settles, I am content until some troubling finger disturbs the pattern. Then, if I can, I wipe clean, restore a new order. Postmodern Craig might roll his eyes at this modernist admission but, more likely, he would ask if the dust can ever really settle or, if it does, settle evenly; if what we call dust, like language, is simply a way of disguising and defining what is there; if we can talk about the dirt that is left behind after everything is wiped clean. In other words, he would more likely remind me of the easy slide from dust, to dirt, to death. I write to dust over what disturbs, to be done; Craig writes to disturb the dust, to begin. And that is perhaps why I allowed my memory to have its way. I wanted Craig in the safety of my construction, secure, gathering fairy dust. I wanted Craig in the house without ghosts, without hauntings. I wanted Craig in the loving arms of Jonny. But Cups teaches me that such desires take daily labor, that just when we think the dust has settled, another finger will leave its print. Nothing comes clean.

Usually, about twice a week, Craig will come into my office, our shared home, and we will chat for an hour or so. We’ll talk about our current projects, students that we celebrate and worry over, and the latest idiocy of the current administration, both on campus and in Washington. I cherish our time together, just the two of us, talking. There is a comfort there, him sitting in the chair always ready for his arrival; me, across the desk, leaning back, taking him in. There is a devoted and loving comfort in that collegial exchange, although I always feel he has much more to offer than I do. There is a comfort in seeing him there, like me, just talking. Less often, I go to his office. When I do, I am always welcomed but, more often than not, he has to clear a space for me to sit. Perhaps the clutter is intentional, a way of being cautious, a way of deciding who can safely be let in. I am, quite honestly, more comfortable when we chat in my office. And that too may be why my memory storied Cups the way it did. It is easier for me to have Craig come to my office, come to my place of comfort. It is easier for me to read Craig like me.

Friday nights are movie nights. With our partners, Mary and Jonny, we often take in the latest release that Carbondale manages to get. Afterwards, we are off to Denny’s for a bite and conversation. Usually we start by talking about what we have just seen but before long Jonny and Mary will start tracing the actors’ previous credits, their favorite scenes from another film which, of course, is a homage to another film which was the third in the series by such and such director whose last film appeared seven years ago, only because he was able to land such and such actor for the lead who had already appeared in two films that year with co-stars so and so, who …. Craig has the skill but not always the inclination to join in. I’m usually lost after the conversation leaves what we have just seen. Sometimes, during such conversations, Craig and I will catch each other’s eye, wanting more. When we depart, we hug, I believe, with love. Mary and I return to our white walls, comfortable, safe; Craig and Jonny drive to their overloaded book shelves holding the weight of the read and unread, to their half-finished craft project awaiting their hands, and to a broken cup, so full, on their windowsill.

Sufficiency Enigma Once Again

Any essay that wishes to applaud necessarily comes forward as a broken cup, filled with the love it knows how to give. It is never enough, never sufficient. Such a claim, of course, is only to repeat the postmodern warning of language’s slippery deceptions and unachievable dreams. Moving forward with postmodern caution, with the skeptic’s eye for language’s tricks, with the predilection to disrupt easy pleasures, it becomes difficult, if not naïve, to celebrate when language satisfies. But, Cups does satisfy, both in my original reading and in my current one. So, I am left as a critic who writes of Cups, insufficiently, trying to tell of Cups’ pleasures, trying to offer in words a sufficient account, trying to deny what postmodernism teaches. Despite my effort, I find myself wanting more. But ultimately, the more I want is Craig’s to give. I want Craig to say, “Enough.”

I long for the “enough” I imagine Jonny felt when he listened to Cups. I see him there in the audience, sitting erect, nodding as Craig moves through the piece. He is taking the show in, like food, like a lover’s touch, like salvation. Even now, whenever the show is referenced, a knowing smile crosses Jonny’s face, a smile that remembers how the show names their love, how it says publicly that they are connected, regardless of how others might wish to narrate them. But that is too much to ask. Instead, I must content myself with my remembered encounters, to settle for my own sense of “enough,” to relish my own satisfactions.

I am sitting there, head cocked to one side, leaning in, not wanting to miss a word. I know I am in the presence of something special, something magical. The show whispers in my ear. Others in the audience drop away. It is speaking to me, telling me what everyone, myself included, needs to hear. I am in the café, watching the waiter maneuver among the tables, coffee pot in hand. I am on my knees in the bookstore, looking up to a stranger who asks for nothing more than a moment of human contact. I am in the bathroom stall, reading “KILL FAGS.” The language carries me along, placing me here and there. I listen to it turn, turn again, and turn back on itself. I applaud its elegant work even while it works on me. I am inside and outside its construction, amazed, taken.

I watch Craig, his sleeves rolled up, moving on stage. There is a quiet there, a softness, an invitation. It seems as if his body is always full front, although that is not actually the case. It seems as if his voice is some combination of a cat’s purr, a glide in the wind, and the deep beat of a drum. He is a panda bear, a peeled grape, a cracked acorn. And he speaks to me, sharing what I imagine he wants to say when we talk over lunch or in my office, but never quite does. I trust what he says as if it were my own blood.

Cups is, as Peggy Phelan would have it, a rehearsal for death, but not because it offers a neat closure. Instead, it allows death in because, and I do not exaggerate here, it is impossible for me to imagine anything better. It comes to me as an argument, so richly nuanced, so carefully articulated that my understanding of love is forever changed. It comes to me as a poem, so finely crafted, so elegantly stated that I am stunned by its electric current. It comes to me as a gift, so generous, so right that I am incapable of responding in kind.

So, when the show ends, I greet Craig with an embrace. I stand there holding him, not wanting to let go, not wanting this moment to end, and I utter what I can manage: “Oh, Craig. Wow!” When we separate, I leave saddened and elated. Only later do I recognize myself as a parasite to a host, feeding, taking but giving nothing in return. I write now, insufficiently, in the spirit of a return, wanting more—more skill, more grace, more Craig than I am capable of conjuring. I will crumple these pages and place them on my windowsill.

Works Cited

Gingrich-Philbrook, Craig. Cups (Sufficiency Enigma, 1999). Kleinau Theatre, Carbondale, IL. 2-4 Dec. 1999.

Gordon, Avery F. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minnesota: U of Minnesota P., 1997.

Phelan, Peggy. Mourning Sex: Performing Public Memory. New York: Routledge, 1997.