| Shoring Up Hegemonic Masculinity: Exaggeration, Mobilization, and Excuses |

Many of the texts on the Internet work very hard to shore up hegemonic masculinity, endorsing and envying the privileges held by Bill Clinton, even while lampooning him for, perhaps, performing masculinity too well. Clinton’s masculinity is secured in these texts in three ways: 1) through exaggerating numbers of sexual partners; 2) by mobilizing other, complicit masculinities in his performance; and 3) by excusing his actions with biological or Freudian motives. Like the indicative social drama, these cultural performances critique individual rule breaking, but never question the phallocentric center that is masculine sexual pleasure. In the Starr Report, Lewinsky’s testimony relates that: “Earlier in his marriage, he told her, he had had hundreds of affairs; but since turning 40, he had made a concerted effort to be faithful.” Jokes on the Internet constantly reference these numbers, recalling tall tales and hyperbole of traditional folklore:

• How is Bill Clinton different from the Titanic? Only 200 women went down on the Titanic.

• How did Bill manage to create such a large gender gap in the '96 election? One woman at a time. • Bumper sticker seen on Arkansas car: "Honk, if you haven't had sex with Bill Clinton." • How many women does it take to satisfy Bill Clinton's sexual appetite? It takes a village. • In a survey of over 500 women, when asked if they would make love to the president, 83 percent of them responded, "Never again."[10] Clinton’s famous disclaimer, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Ms. Lewinsky,” is performed anew on the Internet: “I didn’t have sexual relations with that woman . . . or that woman . . . or that woman . . . or that one over there either.” Exaggerating the numbers is matched by exaggerating Clinton’s sexual prowess and capacity.

• What do Bill Clinton's dick and a Chevy truck have in common? They're both like a rock.

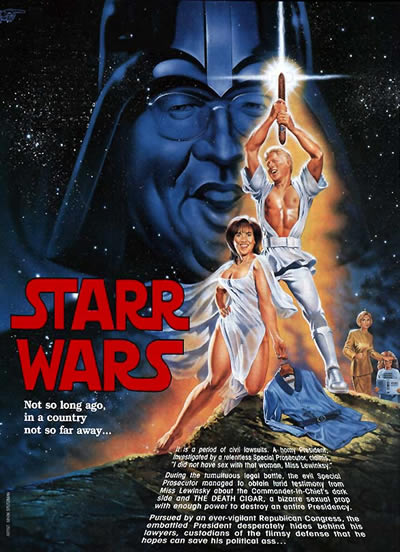

• A new Clinton bumper sticker: "Vote for the Man Who's Always on Top." • You can say what you want about Bill, but you have to admit he’s a very upright man. • Hillary Clinton arrives at St. Peter’s Gate. On the wall are giant clocks. She asks why there are clocks in eternity. She is told the clocks measure adultery and that every time someone commits adultery the clocks tick forward just a little. She asks to see her husband’s clock. St. Peter says, “Because your husband was President of the United States he has the grandest clock of all, but you can’t see it because God likes to keep it in his room and use it as a fan.” These jokes, circulating in and through the Internet, the late night talk shows, talk radio, and word of mouth, bolster and endorse hegemonic masculinity’s privileged access to sexual relations with women. While promiscuity is certainly implied, it is not judged as deviant or immoral—the usual condemnations when gay men, lesbians, and heterosexual women have multiple sex partners and engage in a variety of sex acts. Indeed, sexual prowess, masculine privilege, and antagonism is fun. One particularly entertaining rendition of the indicative social drama grafts the story line onto another iconic cultural performance in which enemies and allies are already scripted: George Lucas’ Star Wars. This text captures the constructedness of masculinity—as idealized body, spirit, and deeds thoroughly undone by its faulty performance. Neither Bill Clinton’s nor Mark Hamill’s body is accurately rendered in this text, but instead the hero is drawn with the white muscles of other iconic filmic heroes, Tarzan, Hercules, and Rambo (Dyer). His heroic, idealized body, however, is brought down by the spirit’s inability to control another sexual icon/weapon: “THE DEATH CIGAR, a bizarre sexual prop with enough power to destroy an entire Presidency.” Clinton is also thoroughly uncourageous in his role as hero. The text reads: “the embattled President desperately hides behind his lawyers, custodians of the flimsy defense that he hopes can save his political ass.” Hegemonic masculinity is also secured by mobilizing other, complicit masculinities—both friends and foes. “Lord of the Flings” is amazing testimony to the staying power of the sexual social drama: December 19, 2001 marked the theatrical release of The Fellowship of the Ring; the last day of the Impeachment Trial was February 9, 1999. Indeed, masculinity is always performed in relation to other men; its accomplishment measured and evaluated by betters and lessers. In his analysis of the Kama Sutra as a thoroughly heterosexual text, Gargi Bhattacharyya writes,

Although the focus is upon pleasure, not reproduction, the logic of heterosexuality bubbles up through every crevice of the text. This is the heterosexuality that assumes male sexual pleasure as its center. . . This central role is determined by social power, as always—so other less powerful men can appear as side characters, another option among the sexual servicers of [male] citizens. (18)

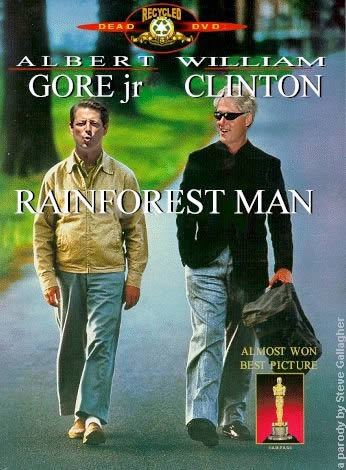

All quest dramas are masculine, whether Star Wars or Lord of the Rings, the gender roles firmly entrenched in embodiments and enactments of heroism.[11] The concomitant sexual roles, “other less powerful men,” staff, consultants, and friends also “service” the President with spin jobs. With hegemonic masculinity at its center, no man in the social drama is left untouched by commentary on the Internet. Al Gore, already institutionally one down to Clinton, is most often portrayed as asexual and decidedly boring. The occasional pairing of Gore and sex points to Clinton.

• What did Al Gore say when he heard of Clinton’s troubles? I’m only one orgasm away from the Presidency!

• Al and Bill were discussing pre-marital sex. Al asked Bill, “I never slept with my wife before we were married, did you?” Bill replied, “I’m not sure, what was Tipper’s maiden name?” The most interesting graphic rendition of Gore’s one-down status is “Rainforest Man.” The brushstrokes that paint hegemonic masculinity as potency, prowess, countless partners, and on top of both women and other men are a storehouse of cultural expectations for the masculine. At the same time, these same portraits must also deal with the fact that Clinton--stupidly, clumsily, and foolishly--got caught “thinking with his cock." These jokes shore up hegemonic masculinity with excuses most often centered in a biological determinism or a Freudian read of unresolved conflicts. A host of cock-for-brains- jokes are grafted onto the President: “Why is there a hole in the end of Bill Clinton’s penis? So he can think with an open mind.” Most jokes rallied around the biological imperative for masculinity, doing what comes “naturally” with willing women. "The White House scandal wasn't really Bill's fault, it was just something he got sucked into." Or, “I’m with stupid.”

To have the Phallus is to be impotent, and to live under the horrifying secret of one’s own inadequacy to the ideal. Under patriarchy, men had the double standard to hide behind; for women in post-Oedipal society, the consequence has been more of a double bind. And nowhere is this double bind more effectively embodied than in the handy opposition between Hillary Clinton—the middle-aged female professional as icy superego—and Monica Lewinsky—the sassy young professional of leisure. If Hillary is all work, then Monica is all play, the ‘liberated’ female libido of the post-Oedipal order. (557)

The Freudian read is also evident in Richard Schechner’s analysis: he casts the characters in the social drama in Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, with Clinton as Oedipus and Hillary as Jocasta. Even Linda Tripp becomes a “shepherd and messenger,” “small timers in ancient Thebes” who “nail the case against Oedipus” ("Oedipus Clintonius," 5). The Oedipal connection is not lost on the folk of the Internet, however. In clear testimony to their critical power, another Freudian read of the phallic stage of psychosocial development is brilliantly played out in a web page entitled “Oedipus Prez.” The text begins:

We’ve seen a seemingly endless parade of women get in front of the camera and claim they were sexually harassed by—or had sex with—Bill Clinton. Is it all about power or is he simply oversexed? Well folks, Tammy and her sandbox sleuths have proposed a new theory. It’s an Oedipal thing. They all look like his mother! We dug up photos of the women in question at the time of their “alleged” involvement with Clinton. Examine the following and draw your own conclusion.

The head-shots begin with Virginia Kelley (captioned “Dear old mom when she was young and vivacious. Doesn’t she look eerily familiar??? Big dark hair, full lips”), move through Paula Corbin Jones, Monica Lewinsky, Gennifer Flowers, Kathleen Wiley, and end with Hillary Clinton (captioned “No wonder Hillary isn’t getting any action—she doesn’t look like mom!”) The critique of Clinton’s infantile, impulse control problems on the Internet doesn’t end, however, with his Oedipal (or her Post-Oedipal) leanings. The most common, and enduring, item in the Internet corpus is the Dr. Seuss’ version of Clinton’s grand jury testimony, casting both Kenneth Starr and Bill Clinton in Green Eggs and Ham.

I am Starr. Starr I are.

I’m a brilliant barri-star. I’m here to ask, as you’ll soon see, Did you grope Miss Lew-in-sky? Did you grope her in your house? Did you grope beneath her blouse? Did you grope her on a train? Did she blow you on your plane? I did not do that here or there! I did not do that in a chair! I did not do that anywhere! I went not near her giant hair! I broke some rules my Mama taught me. I tried to hide, but now you’ve caught me. I do implore, I do beseech, do not condemn, do not impeach. I might have got a little tail, but never, never did I inhale.[12] Casting the antagonists in Dr. Seuss’ fantastic worlds is social critique that serious apprehension of the social drama missed: the Starr-Clinton battle over high crimes and misdemeanors is turned into silly, whimsical rhyme more suitable for the nursery than the state house. The relentless accusations and constant denials mirror the Seuss text not only in form, but also capture the Starr Report’s description of sex acts: “grabbing, groping, poking, and licking that read like teenage foreplay” (Langman 524). Sallie Tisdale argues that American attitudes about sex are “adolescent; there is no other word for our restlessness and preachy finger-shaking” (14). The Clinton deposition as “done by Dr. Seuss” critiques this perpetual adolescence and the “preachy finger-shaking” performed by both Starr and Clinton. One metamessage in this text is that everyone needs to grow up. Masculinity in these texts is constructed via several routes: as a sexual achievement—measured in numbers of partners and in excessive prowess; as a gendered accomplishment—related to and enabled by other masculinities; and as a process of psychosocial development. Only within the third category does Clinton “fail” to evidence an ideal masculinity evidenced by controlled rationality. Victor Seidler writes:

As men we do not want to be thought of as "unreasonable" or "irrational", for this is to be thought of "as a woman". We learn to identify our masculinity with control as domination of our emotional lives. It is because we can control our emotions that we can know we are men. This is a difficult taboo to break, for it challenges quite central cultural notions. (16)

The convenient Freudian read (Clinton’s unresolved Oedipal conflicts or Lewinsky as ‘liberated’ female libido) marries with the biological imperative argument (he only did what comes “naturally”) to absolve Clinton of responsibility for his lack of control. This absolution reveals the constant fiction that is hegemonic masculinity and our cultural insistence that its privileges not be undermined. The social critique available in these texts never questions the privileges of white masculinity, but it does critique Clinton’s inability to perform its particulars. Real men, these texts maintain, don’t get caught with their pants down. |

This social drama turned entertainment capitalizes on the characters, story lines, and conflicts of the heroic quest that is Luke Skywalker’s confrontation-reconciliation with his nemesis-father, Darth Vader. While the heroic quest of mythology makes no mistake about who is good and who is evil, Starr Wars bends the plot structure to spread blame across the dramatic landscape, and there is plenty to go around. While few Americans could or would endorse Clinton’s actions, Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr emerges as a villain of monumental proportions. Joan

This social drama turned entertainment capitalizes on the characters, story lines, and conflicts of the heroic quest that is Luke Skywalker’s confrontation-reconciliation with his nemesis-father, Darth Vader. While the heroic quest of mythology makes no mistake about who is good and who is evil, Starr Wars bends the plot structure to spread blame across the dramatic landscape, and there is plenty to go around. While few Americans could or would endorse Clinton’s actions, Special Prosecutor Kenneth Starr emerges as a villain of monumental proportions. Joan  Even if the punned rhyme on Lord of the Rings was too good to pass up, this critique continues to endorse hegemonic masculinity even as it lampoons Clinton’s enactment. Casting Clinton as “Free Dough Bagits” turns Frodo Baggins’ reluctant quest to save Middle Earth into Clinton’s selfish quest “to do them all.” The production company, “Same Old Line Cinema,” recalls not only Clinton’s governance by polls, but his staffers’ constant spin during and after the two-year drama. In this text, Clinton’s friends, consultants, and fund-raisers, Terry McAuliffe and James Carville, are cast as “Flim Flam” and “Scrotum Smearool,” sidekicks in Clinton’s performance of masculinity who unfailingly “stand by their man.”

Even if the punned rhyme on Lord of the Rings was too good to pass up, this critique continues to endorse hegemonic masculinity even as it lampoons Clinton’s enactment. Casting Clinton as “Free Dough Bagits” turns Frodo Baggins’ reluctant quest to save Middle Earth into Clinton’s selfish quest “to do them all.” The production company, “Same Old Line Cinema,” recalls not only Clinton’s governance by polls, but his staffers’ constant spin during and after the two-year drama. In this text, Clinton’s friends, consultants, and fund-raisers, Terry McAuliffe and James Carville, are cast as “Flim Flam” and “Scrotum Smearool,” sidekicks in Clinton’s performance of masculinity who unfailingly “stand by their man.”  This parody is particularly telling as an endorsement of the Doyle’s five-pronged formula for masculinity: success, independence, aggression, sexuality, and its obverse “Don’t be feminine.” Clinton as Tom Cruise’s character successfully fulfills all five commands, especially when drawn over and against Al Gore as Dustin Hoffman’s autistic character who lacks all markers of masculinity. Indeed, the office of Vice-President has been compared to the role of the First Lady—both positions are feminized and secondary in relation to the President (

This parody is particularly telling as an endorsement of the Doyle’s five-pronged formula for masculinity: success, independence, aggression, sexuality, and its obverse “Don’t be feminine.” Clinton as Tom Cruise’s character successfully fulfills all five commands, especially when drawn over and against Al Gore as Dustin Hoffman’s autistic character who lacks all markers of masculinity. Indeed, the office of Vice-President has been compared to the role of the First Lady—both positions are feminized and secondary in relation to the President (