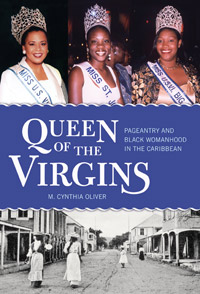

M. Cynthia Oliver's Queen of the Virgins: Pageantry and Black Womanhood in the Caribbean examines the world, history and performative impact of beauty pageants in the Virgin Islands. In this book, Oliver tackles the issues of politics (state, local and within the beauty pageant industry); nation building; national identity; class structure, along with its ties to colonialism and slavery; and power, along with issues of individual identity and mediated image.

M. Cynthia Oliver's Queen of the Virgins: Pageantry and Black Womanhood in the Caribbean examines the world, history and performative impact of beauty pageants in the Virgin Islands. In this book, Oliver tackles the issues of politics (state, local and within the beauty pageant industry); nation building; national identity; class structure, along with its ties to colonialism and slavery; and power, along with issues of individual identity and mediated image.Oliver, an associate professor of dance at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, delves into the world of pageantry as performer, historian, and postcolonial cultural critic. In her introduction, Oliver details the evolution of queen pageants from the early beginnings of the Virgin Islands. Oliver describes these pageants as rehearsals of intra-class politics and that the pageants allowed the women to solidify their place in local society (4). She notes cross class investments from the local business community and grassroots support. At stake in the culture of pageantry in the Virgin Islands is the celebration of the Black body, the impact of intra-island commerce, assimilation and survival tactics used by Black females in the days of slavery, and how these pageants disrupted the conventional power dynamics of colonial relations. The main premise of Oliver’s argument is that pageants are signifiers of attitudes about sexuality and womanhood as related to race and class stratifications (5). From this vantage point, Oliver shows how the idea of nation is gathered into issues of politics, identity, and nation building along with the global market for pageants and conversely how that globality succumbs to local tastes. The performative scope of pageantry includes self-definition and economic survival of the region, sociopolitical relationships, and a gendered national consciousness. While feminine power is highlighted throughout the book, it plays against a leitmotif of male power and politics as they impinge on the pageants themselves.

Part One is designated “The Before-Time Queens” and Oliver uses the body corpus as a metaphor to identify specific increments of time (historical, sexualized, recuperated, and moving) and assigns specific moments in history to each “body.” To have the “body” enumerated and connected to a specific moment in history unveiled the intricateness and historical importance of the performative function of pageants in the Virgin Islands. Also by attaching a historical time line to the evolution of pageants in general and the Virgin Islands in particular, the progression from a slave’s dance to the sophisticated image of today’s pageants, revealed how the Black female body (past and present) is gazed at as an appropriate representation of the identity of the Virgin Islands. Furthermore by using the “body” as a metaphor and map, Oliver unveiled the behind the scenes use of political power as key to the why, the how, and the when of the emergence of the queen and the performances associated with being crowned queen.

Part Two is designated “De Jus Now (Modern) Queens”. Oliver’s approach to this part of her book solidifies the intertwining of nation building, national identity, politics and power. The focus of part two is more a critique of state politics and identity building than portraits of the women who chose to participate in the process of becoming queen. Participants and the pageantry appear mainly as platforms to define the Virgin Islands’ local identity within the global market. Oliver addresses issues of commodification, use value, class mobility, and the heavy burden of maintaining the heritage/culture of the Virgin Islands and places these burdens on the performativity and function of beauty pageants.

Part Three is designated “I Come; You Ah Come (I have arrived; you will arrive)” and supplies the perspective that there was a lack of appreciation of the physical attributes of the individual contestants. Each contestant was required to be re-molded to meet the expected visage of a beauty queen. She was taught appropriate manners and mannerisms, and in some cases was required to live with a family that exhibited these ideals. She was also tutored in posture and poise, coiffed and groomed to meet expectations - expectations of the promoters, sponsors, western/global ideals of beauty queens and at the same time exude the national identity of the Virgin Islands. In addition to those requirements, she was expected to perform in the local beauty pageant as a positive role model and champion for her specific island or city or business sponsor. An interesting side bar conversation was with regards to the gay community and their participation in the local pageants. Further development of this conversation, I believe, would have allowed the reader to better understand the implications of the re-molding and re-tooling of the contestants. Why? Because the functions that Oliver alludes to regarding fashion sense and astuteness to beauty were considered as positive and essential to the success of the contestant. The gay community (apparently) furnished an air of sophistication with regards to style (clothing, hair, makeup and appropriate runway walking) and approval of the physical attributes of the now finely re-molded contestant as she participated in the various local, regional and Island beauty pageant events.

Overall Oliver’s dissection of pageantry and Black womanhood in the Caribbean facilitates the realization that beauty pageants are more than about beauty, poise and grace. The pageantry in the Caribbean Islands is steeped in history and tradition and is culturally intertwined in the psyche of the peoples of the Caribbean. She also gives full attention to the underpinning issues – politics, power, nation building, national identity, and place in the global market, colonialism, slavery, individual identity and mediated image. Oliver deftly used the performativity of beauty pageants to reveal the intimate, intricate and fragility of the evolution of The Queen as being a mainstay in Caribbean culture and as being an identifiable figure in a rich history that spans from the days of the slave to colonial governance to the present.

— Kim Higgs, University of North Dakota