Except for images (see above), this work is licensed under a

Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License..

An Anecdote From the Archive

supplement to "Abstract and Brief Chronicles: Creative and Critical Curation of Performance"

Justin B. Hopkins

Given that the event itself is gone, never to be reproduced, it’s little wonder then that theater historians like to return to what can be captured of the event, to the chronicles, to the archives, to the basic repertoire data: to the idea that something happened at a particular place on a particular date and with these people. Given this over-determined concentration on limited material, surely it’s not just curators, archivists and librarians who get annoyed when programs don’t give the date of a performance, or when the slip saying that the understudy will be performing has gone missing?To build my toire-chive, I relied on the material held by the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, the repository of the Royal Shakespeare Company’s official production records. On my first day accessing the Trust archives, I requested all materials related to Trevor Nunn’s King Lear, the final production in the Complete Works Festival. I received various RSC mailings promoting the production, the program, and photographs taken by Malcolm Davies. As I made my way through these pictures, glancing at the back of one, I noticed that the handwritten label identified Goneril as being played by “Melanie Jessop (understudy).” This was an exciting discovery.

— (Kate Dorney 22)

On April 2, 2007, just before the final preview performance, Jessop assumed the role of Goneril after Frances Barber, the actress originally cast in the part, injured herself. The RSC delayed Press Night until Barber’s full recovery and return, roughly six weeks later. I attended Jessop’s first performance of Goneril, and I wrote the following, beginning to my toire-chive entry on the production:

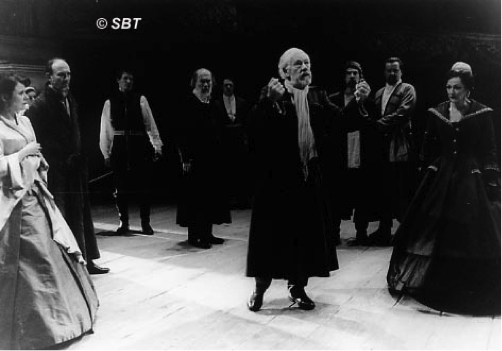

Monday, 2 AprilUntil that moment in the archive, I was unaware of the existence of any photograph of Jessop as Goneril, so to find one was remarkable. However, this picture was taken from behind Goneril, showing only her back, so I quickly skimmed through the following photos until one surfaced showing Goneril from the front. Shot in Act II Scene 4, Lear is the center of the image, gazing heavenwards as he demands, “You heavens, give me that patience, patience I need!” On his right stands Regan, and on his left, Goneril… but it doesn’t look like Melanie Jessop.

King Lear. Produced by the RSC. Performed in the Courtyard Theatre.

– It’s the understudy’s dream… or nightmare. How nerve-wracked must Melanie Jessop be? Twenty-four hours ago she was Second Gloucester Servant, handing Edmund a glass of wine.

Now she’s Goneril. Now she’s telling Ian McKellen: “I would you would make use of that good wisdom, whereof I know you are fraught.” The pressure would crush me, I’m sure. But, feel it as she must, she doesn’t show it. …. Overall, Jessop’s Goneril is, perhaps, a shade more emotionally reserved than Frances Barber’s, but it’s still a performance worthy of the company.

I flipped the picture over. Again, Jessop’s name was written in black pencil, but surely that was Frances Barber in the photo?

What did it matter? Well, a great challenge in incorporating images into the toire-chive is using them more than cosmetically. It’s important that they be more than just pretty pictures, that they actually contribute to the curatorial concept, whatever that may be. In my case, that meant finding images to complement the moments I describe in my base text, my account of the experience of the performance. To adaptively paraphrase Hamlet, I wanted to suit the image to the word and the word to the image, a task hard enough when dealing with normal performance conditions, and even more difficult when dealing with unusual circumstances, like an understudy performance. Showing Jessop as Goneril had previously proved impossible. Would it still? The photos were dated “2007.” I asked the archivist on duty if she could help me find a more precise date, knowing that would determine who was playing Goneril. I explained why I needed to know, and she said she could tell me the difference between Barber and Jessop right away. I wasn’t sure—I thought I knew the difference too—but I showed her the photo. Barber, she immediately affirmed, but she closely examined all the materials herself nonetheless. It was a close call, but we finally both agreed, and consulting another archivist confirmed it. Disappointed not to have a picture of Jessop which would correspond so closely to my narrative, I ordered a digital copy of the image anyway, and photocopied the back of the print before it could be corrected.

This fascinating incident illustrates the potential pitfalls of curatorial error, as well as emphasizing both the strength of the ensemble and the star-centricity of this King Lear. That Jessop could take over such a substantial role with less than six hours of notice is a credit to the RSC prioritizing extensive understudy rehearsal. That the Company delayed Press Night, essentially refusing to allow Jessop to be reviewed, and that it further denied her the opportunity to be photographed (or at least for those photographs to be easily available) is as telling as all the talk—and, admittedly, action—about reinstating the ensemble ethos. Lear showed that despite the genuine changes embraced over the course of the year, the Company would not abandon its former form altogether, as the Festival climaxed in a “long been planned” reunion of Sirs Trevor Nunn and Ian McKellen for “the culmination of their RSC work together,” a traditionally, conservatively, commercially staged world tour of “Shakespeare’s epic tragedy” (Guide 25). The production was undoubtedly a vehicle for iconic Ian and Trevor, as I noted in concluding my toire-chive entry:

– Sir Ian’s Lear is a triumph, no doubt. His exuberant control of the craft of acting is evident in everything he does. Better (and worse) writers than I will no doubt pay tribute to his achievement here. They’ll tell how he enters, looking as much like a high priest as like a king, all golden robes and benevolent scowls and gestures of stern blessing, and how his courtiers prostate themselves before him.

– They’ll sketch his decay, his descent from emotional imbalance into madness, until he strips naked on the heath—oh, they’ll pounce on Sir Ian’s full frontal nudity, I’m sure, with wit and insight aplenty. They’ll say he’s baring his body as well as his soul, and they’ll jest there’s more than one way to measure a master actor.

– They’ll recount the end of his pitiful journey: his howls, his worn, lined face twisted and torn in the agony of loss; his peace-less, struggling succumb to killing grief, cradling his dead daughter in his dying arms. “Break, heart; I prithee, break.”

– Let me be honest. This is not what I’d call a daring King Lear. I sense no risk-taking in Trevor Nunn’s direction, nothing unconventional, except in staging the hanging of the Fool. Apart from this surprise, not to say shock, Nunn offers a relatively safe, conventional version of the play. But why take risks when you’re directing the one of the great Shakespearean actors of his generation, and when you are the great Shakespearean director of your own? Why not simply offer a powerfully distinguished and undeniably affecting Lear, one that will play as well in Stratford as it will in Singapore, as well in New Zealand as it will in New York, as well in Los Angeles as it will in London. This is a world class King Lear, which is a good thing, ’cause the world’s waiting…

Credits

All images used with permission. The two color images are by Manuel Harlan © Royal Shakespeare Company; the b&w image by Malcolm Davies Collection © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust.