This collection of essays reflects on the relationship between craft, art and performance. While much critical work on craft and material culture focuses on the skills and textiles used to construct craft and/or on the cultural influences and impact of craft, the writers whose work is collected here focus on craft’s recent legitimation within the realms of fine arts, philosophy and politics. While craft and the handmade have become constitutive rhetorical and material elements of contemporary self-sufficiency movements in both rural and urban environments throughout the world, handmade objects have also begun appearing in curated gallery shows and museum exhibits. In an attempt to account for these various spheres of influence, this collection is split into 4 sections. The first, “Redefining Craft: New Theory” includes articles about the theoretical definitions of craft and the ideas informing its practice in contemporary culture; section 2, “Craft Show: In the Realm of ‘Fine Art’” examines the ways some traditional craft products, such as quilts, ceramics, letter-pressed print projects and even wallpaper have now been recast in the role of fine arts objects; section 3, “Craftivism” accounts for the potential political efficacy of craft in daily civic life, with essays defining and providing a historical narrative about the combination of activism and traditional craft practices; finally, section 4, “New Functions, New Frontiers” revisits the theoretical terrain of section one and includes essays reflecting on contemporaneous non-traditional uses of traditional craft materials and skills, particularly as crafting makes its mark within the academy in such apparently divergent disciplines as cultural studies, theatre and performance studies, theoretical physics and environmental science.

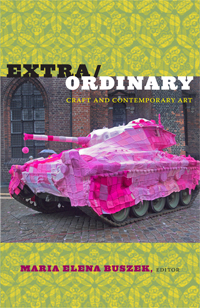

This collection of essays reflects on the relationship between craft, art and performance. While much critical work on craft and material culture focuses on the skills and textiles used to construct craft and/or on the cultural influences and impact of craft, the writers whose work is collected here focus on craft’s recent legitimation within the realms of fine arts, philosophy and politics. While craft and the handmade have become constitutive rhetorical and material elements of contemporary self-sufficiency movements in both rural and urban environments throughout the world, handmade objects have also begun appearing in curated gallery shows and museum exhibits. In an attempt to account for these various spheres of influence, this collection is split into 4 sections. The first, “Redefining Craft: New Theory” includes articles about the theoretical definitions of craft and the ideas informing its practice in contemporary culture; section 2, “Craft Show: In the Realm of ‘Fine Art’” examines the ways some traditional craft products, such as quilts, ceramics, letter-pressed print projects and even wallpaper have now been recast in the role of fine arts objects; section 3, “Craftivism” accounts for the potential political efficacy of craft in daily civic life, with essays defining and providing a historical narrative about the combination of activism and traditional craft practices; finally, section 4, “New Functions, New Frontiers” revisits the theoretical terrain of section one and includes essays reflecting on contemporaneous non-traditional uses of traditional craft materials and skills, particularly as crafting makes its mark within the academy in such apparently divergent disciplines as cultural studies, theatre and performance studies, theoretical physics and environmental science. Like many recent theorists seeking to explain the resurgent popularity of traditional crafts and craft practices, editor Maria Elena Buszek, a cultural critic, curator and Associate Professor of Art History at the University of Colorado, Denver, joins with this stellar collection of interdisciplinary essayists to conclude that handmade objects and their signification of pre-industrial practices of manufacture “provide a “direct connection to humanity” that all too often seems to be missing from contemporary daily life, particularly in the “technologically-saturated, twenty-first century lives” of those in postindustrial nations across the global west (1). But Buszek and her fellow essayists are also careful to remind readers that traditional craft practices and objects, because they resist the application of technology for technology’s sake, have been heralded as culturally significant by philosophers, educators, artists and audiences since at least the nineteenth century, when luminaries such as John Ruskin and William Morris laid the foundation of the Arts and Crafts Movements of Britain and the United States by suggesting that craft (and the traditional, hands-on practices that constitute it) represents a powerful cultural antidote to forces of mechanization, urbanization and industrialization. Like Glenn Adamson’s oft-cited work on the pastoral symbolism attendant to craft in the nineteenth and twentieth century, Buszek’s thoughtful introduction and carefully selected group of essays move beyond the nostalgic fetishization of craft as “authentic” or part of a pastoral cultural mythscape first defined by Raymond Williams in his monograph The County and the City, published in 1973†.

Accordingly, the collection of essays included here seem to try to balance a reverence for the past and for the human scale of craft practices and the hand-hewn objects they produce with a postmodern critical awareness of the increasingly permeable material and theoretical boundaries between pre- and post-industrial manufacture; craft and fine art; and the materiality and performativity of the art object. Thinking critically about the relationship between craft, fine arts, and the rhetorical strategies that have produced and sustained both over time across a variety of geographical and cultural landscapes, the Extra/Ordinary essayists struggle to define a new theoretical and practical approach while documenting and interpreting specific crafts and craft practices including quilts and quilt exhibition; wallpaper and the decorative arts; conceptual ceramics; politically activist knitting; culturally radical curatorial strategies; and even the scientific potential of crocheted sea creatures and plant life to represent hyperbolic space.

Particularly noteworthy is the fact that across the wide cultural terrain comprised by these specific case studies, none of the authors ghettoize cultural idententitarian categories of difference such as sex, gender, race, sexuality, etc. Instead of featuring essays explicitly attendant to these categories either individually or as an aggregate, this collection provides an examination of the cultural politics of identity that is carefully integrated with (and indeed views identity categories as constitutive of) the broader conversation about craft and fine art.

Published in paperback, this collection features full color illustrations, figures and photographs which not only clarify the processes and products referenced in the accompanying articles but also makes the book a joy to read, enhancing as it does the visual performance of the text itself. The inclusion of the full-color documentation of artistic process as well as the art objects produced therefore honors the main premise of the text: that craft can and should be understood as a liminal form of culturally performative fine art. Visual images of both objects and their presentation to the public challenge the reader to recognize the value of the often ephemeral visual and/or live performance in any discussion of material culture; to acknowledge that craft is not only a series of written steps or tacitly inherited folkways but also worthy of formal documentation as a dynamic artistic process within intersecting cultures, economies, and politics; and finally, to appreciate the kind of craft that goes into book design and production, even at a press more traditionally lauded for the academic rigor, and not the aesthetic beauty, of its publications.

note

† See Adamson’s Thinking Through Craft (New York: Berg Press, 2007) as well as his recent edited collection of historical writings The Craft Reader (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010).

— Kristen Williams, Miami University (OH)