The act of Homesteading . . . narratively speaking

Is the commitment to breathe life over the coals of memory.

Words exhaled over memory ignite

and illuminate the ‘still life’ with clarity and precision.

Is the commitment to breathe life over the coals of memory.

Words exhaled over memory ignite

and illuminate the ‘still life’ with clarity and precision.

I am a homesteader. I come from a line of homesteading folk who cleared space for themselves on borrowed land, on land leased from others, because it was their privilege to do so. Like my kin before me, I have scouted a site and staked my claim on a piece of history that is and is not mine to build upon, yet my narrative presence will mark its landscape indelibly. As homesteaders do, I have displaced indigenous growth with structures of my own design, embracing whatever materials are raw and ready to hand: a tree, a lake, a forest of folk, talk-trails snaking through the woods, mementoes skipped like stones across a river-flow of time, the rapid rush of stories falling, the wide field of memory.

I am a homesteader. With autoethnography’s reflexive glance back over the shoulder of experience, I have surveyed the forest for the trees. Mindful of the elements, I have cut down and dug up and joined end to end each mitered tale at my disposal, until I had crafted a home fit for habitation, a hearth round which to raise up my family. To look them in the eye. To pose them for posterity. As tree is to timber, so too is history to homestead. I come from a line of homesteading folk who have used wood and word to make up a place for themselves. On one shore or another.

I am a homesteader. I too know the craft of tongue-in-groove design. I take pride and pleasure in building with stories. Sometimes, I like to fit piece to piece by notching the ends for snugness; sometimes I struggle to right the corners where one tale abuts another. With an eye toward perspective, I have cut each threshold, just so, hoping to maximize view and circulation, yet knowing all the while I cannot hope to encompass the panorama of people, place and time that surrounds me, people who build their own thresholds on our common, historical shoreline. I am a homesteader, using narrative to work the raw material of memory and imagination, so that I might write up my residence on the shores of someone else’s, someone’s larger, history.

In the fall of 2005 I homesteaded my family history. Over the course of three months and in collaboration with a graduate colleague, Amy Pinney [1], I used the raw materials of familial biography to carve a clearing in a social history of local and international significance. My family circumstances were unusually iconic: my parents’ lives unfold against the colonial post-war expansion of northeastern Canada; my father personified the mythos of the bush-pilot entrepreneur as cultural hero; their homestead, Barney’s Ball Lake Lodge, a wilderness tourist resort built adjacent to an Ojibwe reservation, was ‘homesteaded’ on a foundation of environmental racism against indigenous First Nations people. Lastly, although perhaps most personally significant, my parents’ decisive response to environmental poisoning of the Ojibwe dramatizes a model of ethical privilege that continues to ground my adult social conscience [2]. I homesteaded my parents’ story, in order to inhabit, with a mature, critical, and embodied intelligence, the social history and ethical imperatives that were their burden and their legacy to me. And like the line of homesteading folk who are my disciplinary kin, I stake my claims through narrative performance.

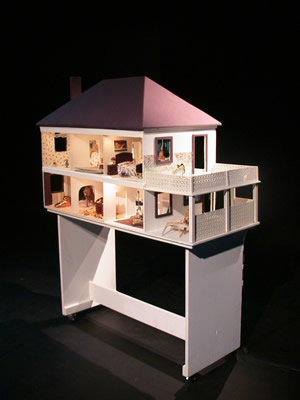

Shadowboxing: Myths and Miniatures of Home was a two act, solo performance presented December 2005 in the Marion Kleinau Theatre at Southern Illinois University. Over the arc of the production, I reconstruct, in media and in miniature, my parents’ wilderness resort, while telling a series of interlaced stories about growing up in the tangle of ethnic, economic and environmental conflicts that attended my childhood. Through a mix of poetic narrative and artifactual reconstruction that transformed the bare stage to Lodge hearth—complete with airplanes, taxidermy, and my dramatized parents—the performance was, itself, embodied scholarship in narrative homesteading. I offer that performance here, in Liminalities, through the combined performance modalities of text and technology. I offer it, moreover, not as a recapitulation of the live event, but as a new heuristic for narrative homesteading as a performance method. Through a fugue of text, video production, and photographic media, this liminal cyber-performance constitutes a new stake in the disciplinary field, a third generational homestead.

Notes

1. Amy Pinney is a doctoral student in performance studies at SIUC with expertise in historical ethnography, autoethnographic performance and directing the one-person show. Amy served as full collaborative partner throughout the conceptual, compositional and staging processes of Shadowboxing.

2. I began using family stories to develop a critical autoethnography of privilege in “Engraving the Silver Spoon: A Critical Caligraphy of Privilege.” The Green Window: Proceedings of the Giant City Conference on Performative Writing. Eds. Miller, Lynn C. and Ronald J. Pelias, Carbondale, IL: SIUC Press, (2001): 66-77. This early essay deploys literary genre as a method for inscribing and deconstructing the ethnic and economic power I have inherited.