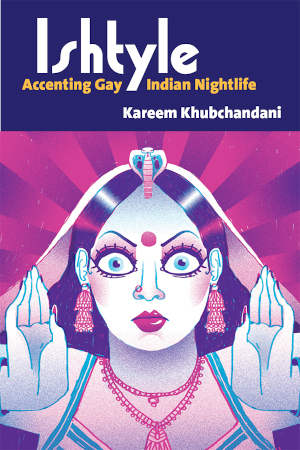

It's not every day that you come across a book that opens with an "Acknowledgement" page that is quite literally a playlist. From RuPaul's "Sissy That Walk" to Kavitha Krishnamoorthy's "Mera Piya Ghar Aaya," Kareem Khubchandani's sonic space calls upon readers to experience a queer nightlife that is transnational and accented, rooted in what he theorizes as "ishtyle." Based on his primary years (2009-13) of fieldwork in Bangalore and Chicago, Ishtyle: Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife is a rich assemblage of modes of queer belonging, dramatized by the author's use of drag as a category of labor as well as a research method. Khubchandani's self-fashioning as LaWhore Vagistan to fill in the void within the Chicago desi drag scene, is coterminous with his preference for a broader "South Asian" affiliation. These overlapping diasporic and performative identifications give him access to ishtyle that is peculiar to "transnational subjects of global economies" (2). Khubchandani reads these negotiations, staged by the cosmopolitan (Indian) "body in difference" as being risky and accented (7). Following José Esteban Muñoz, Kelly Chung, Ramón Rivera-Servera, amongst others, Khubchandani is interested in the quotidian politics of improvisatory performances that are messy but utopian. Hence, though he is aware of the hierarchies of caste, class and race that problematize any easy liberatory assumptions about nightlife, the author remains in awe of its "transformative potential" (26).

It's not every day that you come across a book that opens with an "Acknowledgement" page that is quite literally a playlist. From RuPaul's "Sissy That Walk" to Kavitha Krishnamoorthy's "Mera Piya Ghar Aaya," Kareem Khubchandani's sonic space calls upon readers to experience a queer nightlife that is transnational and accented, rooted in what he theorizes as "ishtyle." Based on his primary years (2009-13) of fieldwork in Bangalore and Chicago, Ishtyle: Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife is a rich assemblage of modes of queer belonging, dramatized by the author's use of drag as a category of labor as well as a research method. Khubchandani's self-fashioning as LaWhore Vagistan to fill in the void within the Chicago desi drag scene, is coterminous with his preference for a broader "South Asian" affiliation. These overlapping diasporic and performative identifications give him access to ishtyle that is peculiar to "transnational subjects of global economies" (2). Khubchandani reads these negotiations, staged by the cosmopolitan (Indian) "body in difference" as being risky and accented (7). Following José Esteban Muñoz, Kelly Chung, Ramón Rivera-Servera, amongst others, Khubchandani is interested in the quotidian politics of improvisatory performances that are messy but utopian. Hence, though he is aware of the hierarchies of caste, class and race that problematize any easy liberatory assumptions about nightlife, the author remains in awe of its "transformative potential" (26).

Khubchandani's nightlife spaces consisting of house parties, bars and clubs are vulnerable to both right-wing censorship and intra-community gatekeeping. The book is divided into three parts that includes six chapters. The first part focuses on the proliferation and suppression of gay visibility in Bangalore, India's Silicon Valley, away from the overtheorized queer cultures of Delhi. Khubchandani's engagement with the Information Technology (IT) industry, and its connection with queer diaspora groups like Trikone, can be useful to assess the centering of Section 377 of Indian Penal Code in Indian queer activism. His navigation of the masculinization of the dance floor, as a result of the entry of electronic music, provides an incisive account of how pleasures can be hierarchized. Though such floors allow for momentary cross-dressing or "feminine performances," they remain closed to most transgender women (49). Khubchandani does not quite distinguish between different kinds of drag labor, so that the labor/work of the hijra and/or transgender person stays only incidental (xxii), if not irrelevant to the gay bodies that occupy these dance floors. Such distinctions could have problematized his comparison of the criminalization of gay nightlife to the banning of female bar dancers, who often hail from lower caste and Dalit backgrounds. Even as he gestures towards inter-caste desire and the sanitization of Indian classical dance forms, his references to non-gay performances remain tangential in this part of the book.

It is not until Chapter 6 that the author elaborates on the linkages between Bangalore nightlife and Dalit performances such as koothu. This allows Khubchandani to revisit the ways in which "South Indian" men desire differently, disrupting whiteness with a fetish for "rawness," that nonetheless ends up with the "erotic essentialization of the Dalit body" (163). It is here that the book manages to do its most nuanced theorization by putting economic boom and nightlife in contradistinction with the precarity of Dalit labor, which is ignored by the neoliberal free market. These accented performances which allow for the political reimagination of gay nightlife, also reifies the "viciously casteiest landscape of middle-class India" (181). While Khubchandani may not have written this book for an Indian market, it is difficult not to notice the casual inaccuracy of the statement—"caste systems were technically abolished after independence" (160). Such a claim, included without a citation can be seen as symptomatic of the author's location in the Global North.

In earlier chapters, Khubchandani theorizes "ishtyle" by complicating the racialized capital that is possessed by some South Asian gay men in the US. While his "accented" tummy does not fulfil certain white desirability criteria (87), the author's ethnographic accounts note how Indian gay men, especially those from the IT sector qualify for the American construct of the model minority. In Chapter 3, that is largely set in Chicago, he notes how his friend Suraj is mistaken for a white man, due to the latter's Caucasian features. The author's conversation with Keshav highlights how Indian gay bodies also "acquire value through (mis)recognition as Arab or Latino," thereby referencing the unpredictability of the dating scene (91). Looking at these interviews as sites of "subject making," Khubchandani is able to engage with the ambiguity of the performative labor by gay men of Indian origin (87). The detailed documentation of "porn performer" Nirmalpal Sachdev's experience also highlights the ways in which Orientalist fantasies and post-9/11 Islamophobia not only shape the American porn market, but also profile brown bodies on dating applications (97, 98). Even though Khubchandani manages to expose mainstream white American assumptions of desire, by relying on the scholarship of Jasbir Puar, Juana Maria Rodriguez, amongst others, he seems uninterested in exploring caste hierarchies of capital flows within the US dating scene.

Khubchandani's immersive reading of Madhuri Dixit and Sridevi's iconic dance performances in Chapter 5 confirms the dominance of mainstream Indian popular culture within South Asian diaspora. His expansion of Lauren Berlant's 'diva citizenship" as a means of survival within dominant publics, makes for a fascinating reading of how queer bodies of Indian origin access Bollywood (145). However, it remains unclear how these cinematic performances of the 80s and 90s circumvent the current "neoliberal aesthetics" of the Mumbai film industry (136). Such a tendency to romanticize the past needs to be interrogated, in relation to the economic liberalization of the 1990s and the diasporic pulls of the 80s and 90s, that are alluded to in earlier chapters. His description of singer Ila Arun's voice as being "rough" also begs for a more detailed discussion on tonality and gender in Bollywood that routinely appropriates both Indian folk and classical music (143).

While Khubchandani's book can certainly gain from a more rigorous engagement with caste capital, in relation to the category of the global, it showcases the ways in which performance studies scholars can rely on ethnography to study the sociality of queer lives. By engaging with drag and curation as research practices and methods, the author renders the nightlife as both liberatory and exclusive, thereby reiterating the messiness that is part of any assessment and imagining of queer utopias.

Note: Special thanks to Aniruddha Dutta for her incisive feedback on an earlier draft of this review.

— Reviewed by Rajorshi Das, University of Iowa

Ishtyle: Accenting Gay Indian Nightlife

By Kareem Khubchandani

[Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2020. 286 pp]

Rajorshi Das is a PhD student in English at the University of Iowa. They are invested in queer studies specific to South Asian diasporas and social movements. When not heavy lifting in classrooms, they write poetry about desires and friendships.