The edited volume It’s All Allowed: The Performances of Adrian Howells is a collection of essays (some of them reprinted) about the life and work of Adrian Howells. It is a reading that I highly recommend no matter if you know Adrian Howells’ work or not. For those who know his work, this manuscript can be a fascinating way of remembering his performances and perhaps discovering more about his personality and life experiences. For those who are not familiar with his practice, this book is an excellent way to get acquainted with this unique, one-to-one performer (i.e., performances with an audience of one). Not only academics, but also a wider public, such as artists and students, can enjoy this extraordinary collection.

The edited volume It’s All Allowed: The Performances of Adrian Howells is a collection of essays (some of them reprinted) about the life and work of Adrian Howells. It is a reading that I highly recommend no matter if you know Adrian Howells’ work or not. For those who know his work, this manuscript can be a fascinating way of remembering his performances and perhaps discovering more about his personality and life experiences. For those who are not familiar with his practice, this book is an excellent way to get acquainted with this unique, one-to-one performer (i.e., performances with an audience of one). Not only academics, but also a wider public, such as artists and students, can enjoy this extraordinary collection.

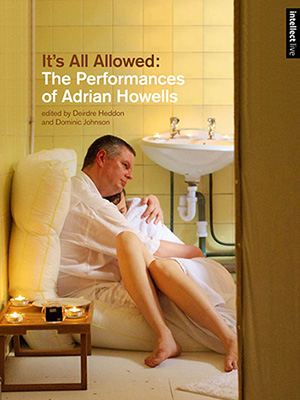

Before presenting the book’s main subjects, it seems appropriate to comment on the beautiful photographs that are part of the manuscript. These are striking notably because some of them are taken from unusual angles and capture Adrian’s facial expressions. One good example is taken from Adrienne: The Great Depression (2004) in which Adrien is lying on a bed and is holding a small angel. His face, wearing make-up to create Adrienne, is illuminated by an orange and red light and he looks straight at the camera (135). Some of the pictures also allow the reader to see how Adrian staged his performances, what the sets looked like and what kind of objects were displayed (302-303). Others capture very intimate moments between the artist and the person for whom the performance is taking place. An example is the black and white photograph – taken during Held (2007) – in which he is lying on a bed and is holding an audience-participant (138). The latter looks asleep but Howells is awake and is looking at the camera. It is an intimate moment in which the man looks relaxed in Adrian’s arms. Adrian’s eyes look vigilant, kind and protective. Another touching photograph is the one in which he is washing a fellow artist in a bathtub taken during The Pleasure of Being: Washing/Feeding/Holding (2011) (268). The man is naked, abandoned in Howells’ arms. Again, the audience-participant looks peaceful, while Howells is taking care of him. When looking at these photographs, one immediately understands the caring and generous aspect of Howells’ performances.

The caring aspect of Howells’ performances entails a darker one, which is the difficulty of giving without receiving. During the interview with Johnson, he admits: “What I think I’ve done is to realise the degree to which my continual giving has been a mask for feeling like I do not need to receive. […] My other concern is that if I’m not prepared to receive, I invalidate my giving” (116). This research of receiving, which is mainly a search for love that characterised Howells’ life, is a theme that comes up in other passages in the book and also emerges in performances, such as Adrienne: The Great Depression (2004) and May I Have the Pleasure…? (2011). In both these performances, Howells reveals all his loneliness, sharing his own life stories with the audience.

The book is divided into 23 chapters of different lengths, each of them covers different aspects of Howells’ work. The chapters are based on interviews with Adrian Howells, archive material, direct observation of the artist’s work, poetry, Howells’ journal entries and audience-participants written and oral feedback. In these chapters, work and auto-biographical elements intersect, since Howells’ performance was a result of his tormented and difficult life experiences. The editors and most of the contributors knew Howells himself and interacted with him during his life. Thus, the chapters include these encounters and the description of moments that they shared together. The chapters are not numbered, and the text is not justified, which can be a bit annoying sometimes, but no doubt this is a way of ‘disobeying’ established conventions, a thing to which Howells himself was committed throughout his life.

The manuscript can be read as a long tribute to Howells’ life and work and is permeated by a sense of nostalgia and sadness, deriving from the grief experienced by his friends and colleagues after his death. The book in itself seems to be an act of caring: toward Adrian (as a memorial), toward the people who met him (as a ‘gathering place’ to share memories of him) and toward the readers (with its accessible style).

Some passages are deeply moving and literally bring tears to the eyes. For example, during her participation in a performance, Deirdre Heddon shares a story with Howells. She tells him that she has always been self-conscious about her hands, because they were “always hot and sweaty”, since she was a child (137). However, Adrian without hesitation takes her hands and holds them “reassuringly, tightly, warmly”. It is a very delicate moment in which we learn about Howells’ sensitivity but also about Heddon’s intimate insecurity. It is remarkable that Heddon decides to share this private detail not only with Adrian during the performance, but also with the readers.

Another poignant description is the one in which Kathleen M. Gough writes about the dream she had after Adrian’s death. Her dream was about his performance Foot Washing for the Sole (2008) and the need to teach other people this practice so that they could start caring more about each other. But the excitement of seeing Adrian again suddenly disappeared: “At some point in this dream, as I waited in the queue, the visual image of Adrian faded and he started to speak to me in a disembodied voice. […] I broke down in a flood of tears and told him I had forgotten – I had forgotten that he was not here anymore” (219). Again, the readers access the intimate universe of Gough who is keen to open up and share this dream with them.

The book also underlines less positive outcomes from Howells’ work. Rachel Zerihan writes about her participation in one of Howells’ performances, The Garden of Adrian (2009). She describes her repulsion for strawberries and her refusal to eat them. However, during this performance, she accepted to eat them: “I don’t like strawberries, yet I ate one for Adrian Howells. Moreover, I ate two” (174). This story shows that the book is not only a celebration of Howells’ performances, but also wants to recognise the problems that arise in the one-to-one performance, where more vulnerable people are unable to say ‘no’. The description of Zerihan eating the strawberries in hesitation is disturbing. But the book is honest about this, the editors do not try to hide anything.

Additionally, the book explores some impracticalities concerning the one-to-one performances that Adrian Howells himself recognised. In his interview with Dominic Johnson (98-119), Howells argues that festivals are not particularly keen in adding his performances in the programme because of the profit loss associated with them. However, they accept to show them because they acknowledge their cultural value. In this interview, Howells says: “But the festival accepts that it’s culturally important that the work is part of the programme, as it has another ‘currency’ that will not necessarily translate into making money” (107).

The economic debate about Howells’ work is developed in "What Money Can’t Buy: The Economies of Adrian Howells" (260-277). In this very interesting chapter, Stephen Greer examines Howells’ receipts, bank statements and contracts that he used to keep. He discovers that only in 2008, Howells was employed by eleven different organisations on short-term contracts (263). This chapter sheds light on the precarity not only of Howells’ professional life, but of that of artists in general. This instability and economic uncertainty linked to the immateriality of this kind of work affected Howells directly (he was obliged to negotiate his salary with festival organisers who often required more performances for less money), to the point that in one of his journal entries, he writes: “how to work consistently. How to make enough money so as not to sign on/claim HB [housing benefit]?” (63). Greer argues that Howells’ performances belong to the “economic logic of scarcity” (266-267). According to this logic, limited supply of performances makes them more expensive and, for this reason, accessible only for few who can pay its price: “Despite ourselves, we understand we have access to a rarefied experience only because we have paid for it and that even if we reject a merely financial valuation, part of the value of that experience is reflected in its price” (274).

Finally, the book undertakes a debate concerning the ethical aspect of Howells’ work in different chapters. Howells’ performances involved touching, kissing feet, holding and body washing. As the participant’s body was the main element involved in them, it was important to ask for consent to create a “safe space” (201). Helen Iball wonders if the simple act of buying a ticket means that an audience accepts anything during a performance (190). She argues that “one-to-one performances create a particular kind of loop where the audience-participant is observant to the way that her/his response is received by the practitioner, with the practitioner becoming an audience to the way that her/his work is received” (201). In this situation, asking for consent seems to be unavoidable, but the chapter makes the reader think about the effects that ‘asking for permission’ can have on the artist’s creative process.

Even though this book covers almost all aspects of Adrian Howells’ work and life (or perhaps because of this), it leaves us with a sense of loss. We regret that we have not had the possibility to be one of his audience-participants, that we have not been at least once in Howells’ s performances, in his arms, under his care, beyond our comfort zone, in that safe space where It’s All Allowed.

— Reviewed by Giovanna Di Mauro, University of St Andrews

Giovanna Di Mauro is a Ph.D. Candidate in International Relations at the University of St Andrews, UK. She holds an M.A. in Expressive Arts in Peacebuilding and Conflict Transformation from the European Graduate School, an M.A. in European Interdisciplinary Studies from the College of Europe and a Laurea in International Relations and Diplomacy from the University L' Orientale of Naples. From 2015 to 2016, she was a Visiting Scholar at the Institute for European, Russian and Eurasian Studies (IERES) at The George Washington University. Her research focuses on artists’ political engagement in Eastern Europe, activism and artistic protest.