In the chapbook, Postkarten aus Deutschland, I map a three and a half month feminist ethnography on embodiment in Germany through ethnographic poetry and self-made photo-postcards. From August 19, 2014 to December 2, 2014, I lived and worked in the city of Mannheim, the eighth largest metropolitan region in Germany located at the confluence of the Rhine and Neckar Rivers in the northwestern corner of the state of Baden-Württemberg, (re)learning the German language after a twenty-one year hiatus. I was enrolled in a German as a foreign language class (Duetsch als Fremdsprache B1: Threshold or Intermediate German) taught by two teachers from a Hochschule in Mannheim and spent Monday and Wednesday nights immersed in culture, grammar, and formal language instruction. I taught a seven-week course on Gender and Interpersonal communication in English at the University of Mannheim where I was a visiting scholar. Many weekends, I traveled by train through Germany with my child and spouse. I ran along the Rhine River three times a week watching the river push barges full of coal, cars, and other cargo. I spent time with a new German friend over wine, coffee, and apple cake practicing the art of German conversation.

Chapbooks

I present this ethnography as a poetry chapbook that I created in a DIY (do-it-yourself) spirit to pay homage to the subversive roots of chapbooks (Hahn 63). Chapbooks represent a part of DIY culture and have been from inception, a medium for political action to a venue for avant-garde and new writers. Many chapbooks are made by hand-card stock sliced with paper cutter, hand sewn, bound with ribbon; they are small, self-contained entities that play with style and form. Poetry chapbooks are usually no more than 40 pages and often center on a specific theme such as Hello Kitty or family trauma (e.g., Faulkner 2012; Faulkner 2015). Of course, some consider chapbooks “more like the trailer for a movie than the movie itself,” however; chapbooks were meant to be small, cheap, and entertaining (Miller 6).

Contemporary iterations of chapbooks have been likened to DIY paperbacks and are popular again in the contemporary poetry world because of the production ease, path to other publications, and risk-taking in subject and/or style. They have changed from their past as a vehicle for the democratization of readership to a democratizing means of production for writers (Miller 6), especially because poetry is difficult to sell. Noah Eli Gordan (¶ 11) writes in Jacket magazine “it is the ease of access to the means of production that defines the chapbook’s unfettering of hierarchy.” Gordon argues that “the chapbook constitutes a crucial nexus of the poetry community; They provide poets a forum to publish poems as an intermediate step between magazine publication and books and in some cases, even instead of books.” Kimiko Hahn (64) considers chapbooks to be like the burgeoning DIY culture, a change from past thoughts of them as solely art books or vanity publications: “Due to a true revolution in the means of production, digital technology has given writers the power to publish their own chapbooks even more cheaply than a Beat poet armed with a mimeo machine” (64). Anyone can take a stapler, ribbon, tape, glue, camera, word processor, and printer and create their own chap.

Feminist presses, often run by one woman, offer spaces for women’s writing and writing that may not be considered “serious poetry” such as that which mentions the domestic sphere and/or babies (Katz). Kristy Bowen of dancing girl press, for example, began her chapbook press to publish the work of women poets: “Projects that were implicitly or explicitly feminist and women-centered. Projects that had an impact on readers both visceral and cerebral” (¶ 2). She writes of admiring an aesthetic where women poets create their own worlds in their poetry and wanting:

to publish the sort of work I thought needed a berth. To promote and propagate women's writing in particular, which in the small press world, still only accounts for less than a quarter of all published. I had started the online zine wicked alice in 2001 with merely an angelfire account and a dream—a mission to provide an excellent forum for up and coming female writers. Going to print with that mission was a logical next step. One big stapler, a Word file, and some cardstock later, we had our first title. Then the next. Then the next. (¶ 1)It is this brazen flaunting of the false dichotomy between the domestic and public sphere, between the private and the public that made creating an ethnographic chapbook an appropriate presentation of my feminist ethnography. Gordan (¶ 11) sums up the power and appeal of chapbooks for the poet (and for this ethnographer).

“…The chapbook in its current manifestation allows poets to enter into a shared life of the imagination while swerving around the dominant paradigms of economic and social space. Whether comprised of an extended sequence, a series of short poems, or a single, longer work, the chapbook, in its momentary focusing and sculpting of the reader’s attention is the perfect vehicle for poetry.”Postkarten aus Deutschland Chapbook

I use a feminist lens in my DIY poetry chapbook, Postcards from Germany, to show the interplay between power and difference (Buch and Staller 113). The poems, images and sounds I present demonstrate the full body experience of learning another language and engaging in culture through language (mis)acquisition; I focus on the concept of embodiment and what it means to learn a language and culture through attention to the senses and the full body ability to feel a language, to notice the “eye” of others when you don’t quite get it, to runs along the Rhine, to the use of public transportation, ordering food, holidays and the usual activities, and to travel as a middle-aged white female body with a kindergartner plus male spouse.

The use of postkarten and the chapbook format plays with the usual way we map trips, how we try and send the most picturesque parts to others for their consumption. Mannheim, for instance, is a city where the streets are laid out in a grid pattern leading to the nickname “Quadratestadt” (city of the squares) and a city slogan—“Leben. Im Quadrant.” This slogan is plastered on city billboards, buses, and street trains. In Poskarten aus Deutschland, you see the not so neat and pretty parts of cultural shifts, what a city would not put on a postcard for sale. I use poetry, sound, and images about my German experience to embody an experience not found on typical postcards. The poems capture what Wanda Hurren calls postcartographia (234). They play with cartography, with map and card, to question what we mean by mapping, place, and position. The use of ethnographic personal poetry highlights how we can use the auto in ethnography to bridge difference (Faulkner 2009). Robin Boylorn claims, “our experiences of difference and place are marked on the body” (313). And this dear audience, is what I invite you to listen for and watch for, and possibly, embody another experience of life in Germany.

Ode to Jetlag

You can be in two places at once,

finally have the here and there

be the same in your fog of where

am I. The language you overhear,

sounds with no meaning,

could be your mother tongue,

English or Deutsch or just noise

you can’t see through,

a peripheral haze with no way

to filter in this place of the in-between

where you can make time warp

and erase the tedium of the everyday.

Deutsch Klasse am Mittwoch (German Class on Wednesday)

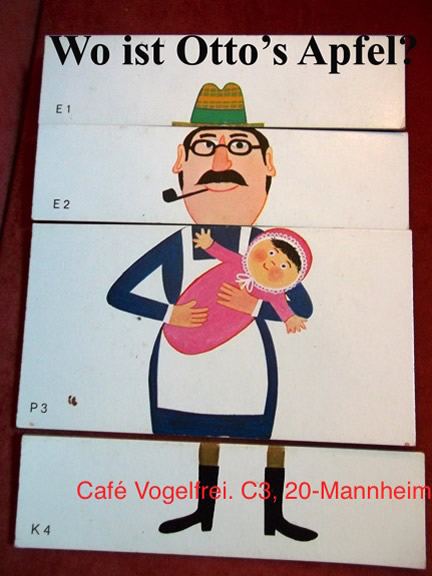

Meine Deutschleherin asks if I’ve seen Otto’s Apfel,

Hast du seinen Apfel gesehen?

“Jaaaaaaaaaaa.” I stutter with emphasis

so the class laughs at the delivery,

my, for once, perfect pronunciation.

I can’t choke out the core of the sentence

tell her where I put Otto’s Apfel,

not the closet nor the Kühlschrank.

Maybe der Apfel ist an der Universität

unter the desk I sat at 21 years ago

in Herr Meinrad’s class, unsere Klatsch

immer about Bier, German plumbing, and fascination

for Gesundheit: I almost see der Apfel, shriveled

and lacking its former heft und fiber

like my language tongue that can’t taste

the difference between hatte und hätte,

my grammar rotten and full of holes, nicht frisch:

Ich hatte den Apfel gegessen.

Ich hätte den Apfel gegessen.

(If only) I had eaten the apple,

I would have eaten the apple (auf Deutsch),

not auf Deutlisch, my hybrid seed of language

that only the other American student in class finds lustig.

Unsere Leherin, Nicola, throws Otto’s Apfel

unter dem Bus and makes us roll after it, sing

about Präpositionen that change their case when they want:

neben|zwischen| |hinter

vor| über unter

auf

an

|in|

As we sing, we wave our hands by Otto’s Apfel,

and I imagine Ottos’s Kopf and where

I would like to put the Apfel.

Kinderspielplatz

Mein Kind shimmies up an impossibly

tall tower of velcroed pleather bands

broken in strategic places,

through the hive of Kinder bodies

to the peak of this structure

her father and I call

—The Trap of Death—

These macht Spaß structures

masquerade as Kinderspielplatz

and appear around every other bend,

durch den Schwarzwald when we laufen

like good Germans and halt before signs//

the spikes of wood carabined together

to make one learn climbing in good form,

no papers to sign, just pay your Euro to ride

metal spirals that slice through cliff sides

for a slick ride down to the sandpit below.

I remember my time before fear

when worry about children was abstract,

unfocused with no existential threats:

Do Germans hate children, oder

do Germans love children? Oder

vielleicht this is true Liebe-Hass,

an engineered belief in Darwin,

a love of sharp edges and fast free falls.

Run the Rhein

Do not begin by the too green Lindenhof

with the stony stare of Princess Stephanie,

the Mannheimer dogs off-leash who get to pee

where they please while you must hold it in.

Start at the urine-soaked graffiti-sprayed

tunnels under the tracks,

do not flinch with the sound of the clack

as the Deutsche Bahn thunders over your head,

dodge the post Wochenende pile of vomit

carnage of used wrappers and bottles

until you cruise out of the fragrant disorder

into the Schlosspark thick with rabbits

like Watership Down, skitter past the murder of crows

that eye you with the eye, you stranger,

they were here first and are hungry,

can outcall the flocks of whiny lime green parakeets.

Have keine Angst, no one will talk to you

as you hear only the flap of your hat

smell the proof that Germans like dogs

better than runners and children.

Stumble over chestnuts, the grit from the Promenade,

into the Waldpark with only suggestions

of the city traffic and sirens, the endless construction.

Do not smell the stench of Ludwigshafen

over the bridge when the wind blows just so.

Try and get lost in this pretend forest

that is better than your dream of Germany,

know there will be no hidden trees for a WC trip.

Decide that public urination is fine and fun

like breaking some half-remembered grammar rule.

Pull up your pants and turn around by the snake-neck bend,

you can chase the cargo ships stacked with stuff.

Laugh when der Schlauch by the spectator benches

elbows them sideways with a strong arm,

so you can not cry this rotten nostalgia into the Rhein

as you limp your leave.

Beschweren Sie sich: 3 Beispiele (3 examples)

z.B.1. Ein Hobby

beschweren sich is to complain,

weigh oneself down, encumber oneself,

okay, ja!, to complain, but epically

like my teacher Nicola says,

everyone needs a hobby

and this is an epic hobby

I learn and practice

to show I can speak German

and weigh others down

with my unencumbered curmudgeonly bitching

z.B.2. Der Verkehr (transportation)

always old men on busses and trains

bitching about their dissatisfaction

with how the rest of us cause pain-

our strollers, accents, and undisciplined

children the kibble they need to feed:

exhibit a. the Mürrischer Mann in Stuttgart

who sputtered about the Turks

and then the woman who had trouble

folding a stroller into closing doors

as the bus stuttered on the climb

to the Schloss Solitude, his swearing

of burdens we were meant to carry.

exhibit b. the Schnurrbart Mann on the fast train

to Freiberg who fussed about children on trains,

flung his papers like unwanted toys,

his tantrum finale pistoned fists

of such force on a tray table,

the train din stopped;

everyone in the car finally focused on him,

the passenger next to my child

moved cars away, the woman with infant

censured to the vestibule toilet.

exhibit c. the Mann in Strapsen who barked

his question at me as I stood beside mein Kind

wedged between the trash and the WC,

no seats on the sole train back to Mannheim

during the planned Bahnstreik-

Ist dass Ihr Kind? Schade.—(Is that your child? What a pity.)

I nod my head and wish he would give

me his seat and coffee instead

of these words I can understand.

a. Mürrischer Mann (grumpy man) b. Schnurrbart Mann (mustached man)

c. Mann in Strapsen (man in suspenders)

Gefühle in Deutsch Klasse (Feelings in German Class)

1. Die Trauer (The Sadness)

I have two weeks left und schon I miss Mannheim,

my life, and get all like weepy American

as I scratch plus and minus signs on notebook lines

next to feelings when mein Lehrer asks, negativ

oder positiv? I pen the Gestalt wrong, all

scribbles up and down, and slash out the sad

signs my German is not prima or toll—

or any other of my Lehrer’s praise—but bad.

At least I’m getting the gloom out of my way

rubbing the feelings of nostalgia

over my notes in an efficient display,

better than being a middle-aged mute und traurig

like the first Deutsch als Fremdsprache class all in German

—no comparing to English = I’ll miss Sebastian who+

never gives in, explains German with more German.

2. Die Angst (The Fear)

I never give in, explain German with more German:

This place is like a Wintertraum mit Grimm magic,

not like boring Ohio where we only do mom-like

chores and homework, and the dog gets ticks.

I try to be a real Mannheimer,

like when mein Kind weint und klagt

that “I miss my dog” and “you love Germany

more than me,” I speak a few words of Tratsch

arrive 10 minutes early to meet

my new German friend because I can’t learn

how to speak un-American and treat

the locals to an echter Akzent as I burn

through a walk in the city’s alphabet street grid

to become more German than the Germans.

3. Der Stolz (The Pride)

I become more German than the Germans

and don’t feel Stolz in all of the American places,

not about my verstehen in class, mein Kind or Mann

who like that I can order their food in these spaces

with Kellnerin draped in Dirndls und Lederhosen,

Germans who are not proud of their nation

or their selves but show pride in gut gemacht clothes

that are more German than Germany. I get this

feeling, share this fetish for all things Deutsch

and Palatine, take my runs along the Rhein,

go places no Mannheimer knows like Bacharach

where we tourists creep along the winery

vines like a tourist blight of red, white and blue

as we dare to drink in all of these views.

4. Der Ärger (The Annoyance)

Shop Windows, Mannheim

I dare to drink in all of these views—

windows with wispy women mannequins,

Dekolleté molded into Oktoberfest Dirndls,

hung over Lederhosen punked-out Männer,

displays more authentic than the Mannheimers

who sport suspenders and check-print shirts

around town, a glass of trockene Riesling in one hand,

a cigarette and a kid in the other, the dirty

smoke refracted onto the facades of shop fronts

and in my face as I stand and frown from the outside,

choke on the effluvium of cost and fashion

mutter that this is not Bavaria, outside

in English, my body warped in a hoodie,

hair frayed, jeans, disordered and strange.

5. Die (Un)Ordnung (The (Dis)Order)

Disordered and strange, hair, jeans frayed,

I cannot bring mein Kind in order

as we drag along the Mannheimer Straße—

Ist alles in Ordnung? Alles klar?—

she darts like an expert frogger

onto the street and knocks a bicyclist

off his pedestal into the corner

as we snake our way to Kindergarten.

Pass Auf! He yells (and not

Ouf Pass! like a real Mannheimer).

Watch out! I yell and pull her back

to the sidewalk as the bicyclist

turns and snips: Schlaf gut Kind!

All of these Germans tell

us how to keep order

like the woman on the train platform

who demands, Do you speak German?

Because that man is taking video of your daughter.

Her last words, as she points to a suited man

with video-phone in hand, and turns away—

And I thought you should know—

mean I must clamp the fun,

bringe alle in Ordnung with mein Kind

who moves time during Bahnstreiks

by tanzen like a kleine pied piper of chaos

knocking strangers off board

the train of forgotten rules.

Leben. Im Quadrant. Mannheim Brezelstände

27 November, 2014

I’ve been here long enough to know

when the graffiti in the pissed in tunnels

under the tracks by the Universität

has been sprayed over with the sheen of new critique,

when the pile of vomit after a Feiertag fest

will be swept away with the green glitter

of broken wine bottles, where the bend in the Rhein

sideways cargo ships, but not long enough to know

where to get the best Brezel, which stand on what corner

shills the most lecker 25 Brezlen I need

for my kid’s Goodbye German Kindergarten Party:

ams, Golden Brezel, Grimminger

Kurpfalz Brezel, Mannheim Brezel Haus?

We all know that ALDI is the cheapest,

so I pretend a walk in the Quadrant

is like a game of Battleship

as I move from L2 by the Schloss,

past Rewe City to Paradeplatz und Stadthaus N1,

where the benches are always full

with early drinkers and exuberant teenagers,

steer left by the Turkish bakeries and Döner

at Marktplatz H2, 1 to F2, 5-10,

to learn why every German test

has a question about shopping at ALDIs:

I fail my B1 German Zertifikat Prüfung hier

as I belly up to the baked good machine

and push the button for Brezel after Brezel.

The alte Frau rudders up on my Starboard side,

sails her walker into my thigh as she presses

the button for her own Brezeln, my hand

moored in the opening of the machine

as the other alte Frau rams into my port side

and beschweren Sie sich in my American ear—

You are taking all of the baked goods

Sie nehmen alle Backwaren!

I pretend like I don’t understand German,

anchor my ugly American hooks in the Brezeln

because I need to eat my way durch Deutschland,

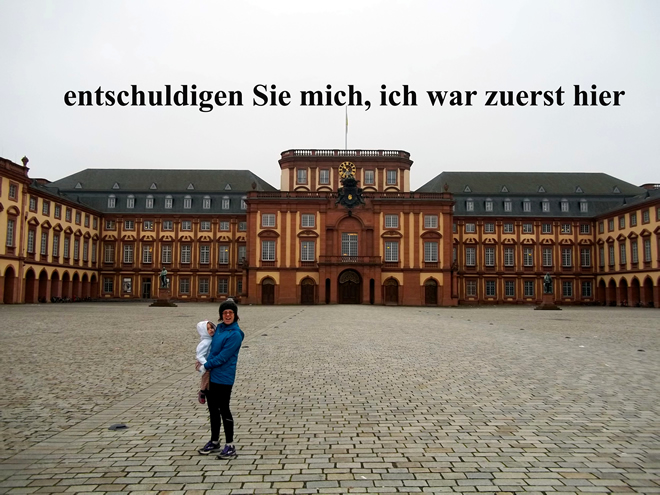

take up space in this country where I catch

only elbows and stares because I can’t say,

Entschuldigen Sie mich, ich war zuerst hier.

(Excuse me, I was here first.)

Acknowledgements

I thank the editors of the following publications, where some of these poems (in different forms) originally appeared: TAB: The Journal of Poetry and Poetics: “Ode to Jetlag” and “Deutsch Klasse am Mittwoch” and Transcendence: “Gefühle in Deutsch Klasse.”

Works Cited

Boylorn, Robin M. “From Here to There: How to Use Auto/ethnography to Bridge Difference.” International Review of Qualitative Research 7.3 (2014): 312-326. Print.

Bowen, Kristy. “about the dancing girl press chapbook series.” n.d. Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

Buch, Elena D., and Karen M. Staller. “What is Feminist Ethnography?” Feminist Research Practice: A Primer. Ed. Sharlene Nagy Hesse-Biber. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2014. 107-144. Print.

Faulkner, Sandra L. Poetry as Method: Reporting Research through Verse. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2009. Print.

Faulkner, Sandra L. Hello Kitty Goes to College: Poems. Chicago, IL: dancing girl press, 2012. Print.

Faulkner, Sandra L. Knit Four, Make One: Poems. Somerville, MA: Kattywompus Press, 2015. Print.

Gordon, Noah Eli. “Considering Chapbooks: A Brief History of the Little Book.” Jacket 34 (2007). Web. 12 Mar. 2015.

Hahn, Kimiko. “Chapbook Renaissance: The Little Book in the Age of Digital and DIY.” Poets & Writers September/October (2009): 63-65. Print.

Hurren, Wanda. “The Convenient Portability of Words: Aesthetic Possibilities of Words on Paper/Postcards/Maps/Etc.” Poetic Inquiry: Vibrant Voices in the Social Sciences. Eds. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 2009. 229-238. Print.

Katz, Joy. “Baby Poetics.” The American Poetry Review 42.6 (November/December 2013): Online.

Miller, Wayne. “Chapbooks: Democratic Ephemera.” American Book Review (March-April 2005): 1-6. Print.

Sandra L. Faulkner is Associate Professor of Communication and Director of Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Associate Professor of Communication at Bowling Green State University. Her poetry appears in places such as TAB, Literary Mama, and damselfly. She authored two chapbooks, Hello Kitty Goes to College (dancing girl press, 2012), and Knit Four, Make One (Kattywompus, 2015). Sense published her memoir in poetry, Knit Four, Frog One (2014), and a co-authored book (with Sheila Squillante) on Writing the Personal (2016). She lives in NW Ohio with her partner, their warrior girl, and a rescue mutt.