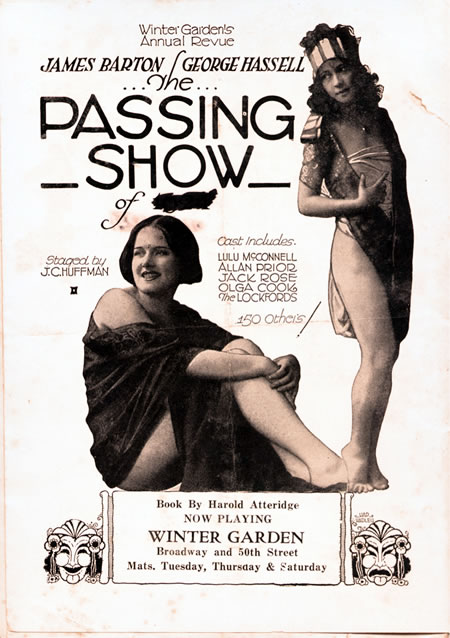

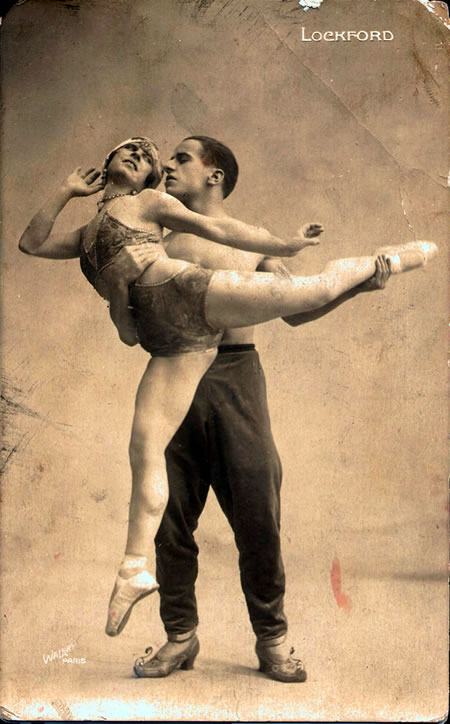

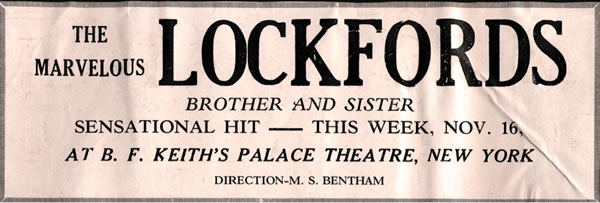

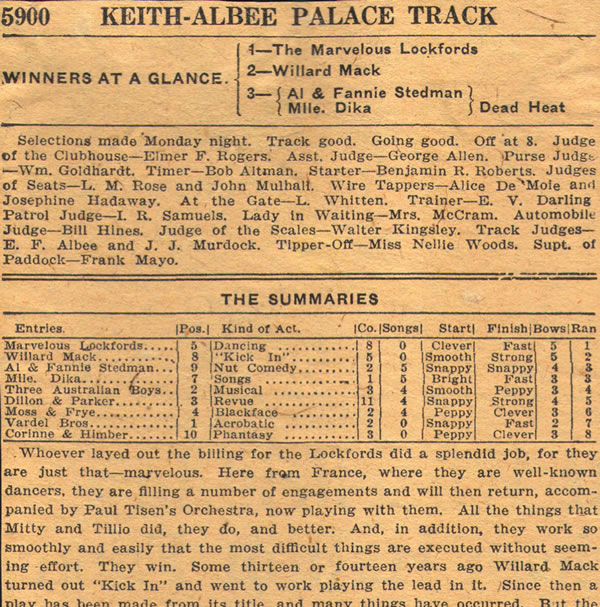

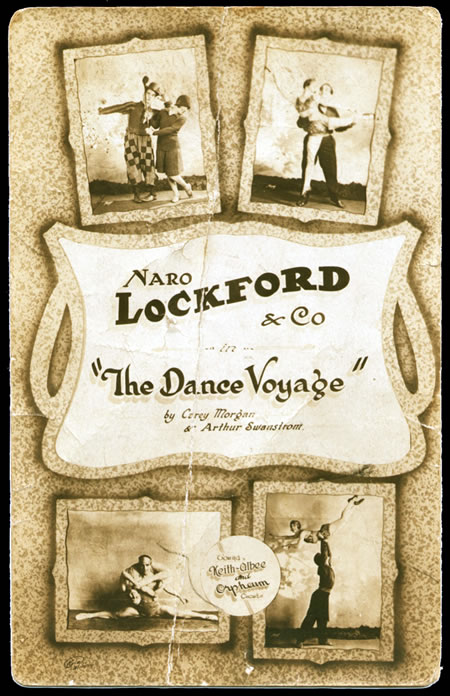

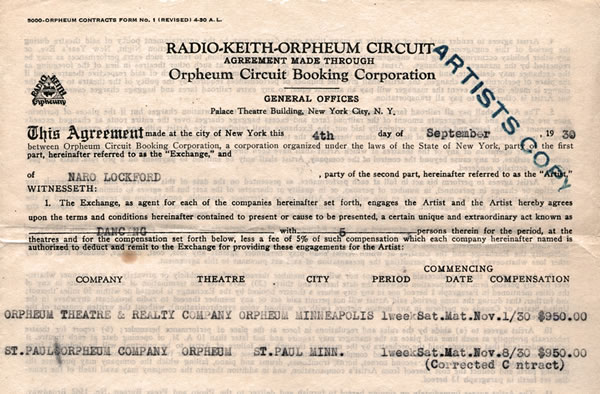

Background: This performance is a culmination of research I have done on my grandfather, Naro Lockford, and his sister (my great aunt), Zita, who worked extensively in France and then in the US vaudeville circuit in the 1920s and early 30s. As the adagio dance team known as The Lockfords, they were bought out of their contract with the Folies Bergere in 1921 by the Broadway impresarios, Lee and J.J Shubert, to dance at the Winter Garden in a Shubert brothers’ revue, The Rose of Stamboul. The Lockfords were met with acclaim and invited to extend their stay. Once The Rose of Stamboul closed, they were invited to perform in two more Shubert revues, The Passing Show of 1922 and The Passing Show of 1924. They extensively toured the US as members of the casts of both these revues managing to retain their position throughout the tour despite the Shuberts’ habit of cutting acts that they regarded as not worth the expense as the tour wore on. Ultimately, after much critical success with the Shuberts’ enterprises, they broke with the Shuberts and formed their own company, known simply as The Lockfords. Zita eventually moved back to France, but Naro, having met and married my grandmother and having fathered two children (my mother and aunt), naturalized as a US citizen and formed his own company called, Naro Lockford and Company. The company toured widely across the US playing in all the major houses of the Keith-Albee and Orpheum circuits, and in Canada, and Mexico before Naro became inexplicably ill and died in 1936 at the age of 34.

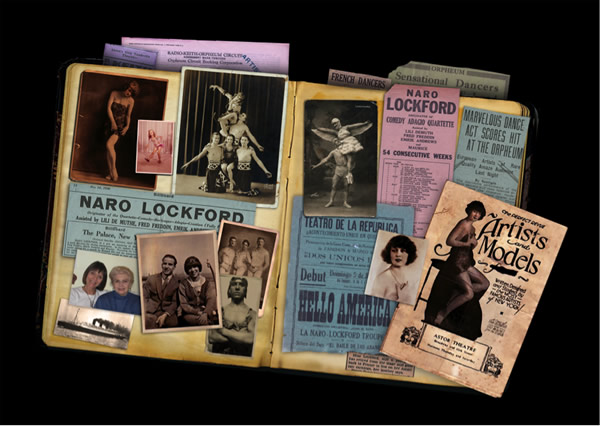

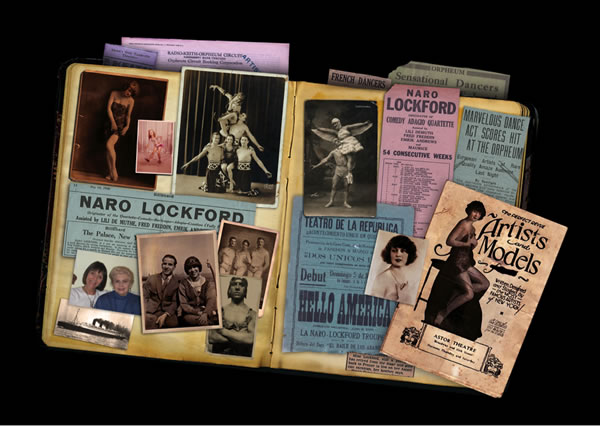

My research on The Lockfords was not only prompted by a familial interest in my relatives. The discovery of a long-ignored scrapbook deep in the recesses of my mother’s closet which contained a thorough collection of reviews and promotional materials of my relatives’ professional life connect my personal interest in my family tale with my professional interest in the theatre. This joint personal and professional interest prompted me to go to the Performing Arts Library in New York City where I found in the library’s special collections two folders full of photos and newspaper articles on my grandfather and my great aunt as well as my grandfather’s obituary. I traveled to Paris and found material in the Biblioteque Nationale on my great grandparents (my grandfather and great aunt’s mother and father) who were trapeze artists in the late 19th Century, noteworthy performers in their own right for they were among the first and reputedly among the best “voleurs” or flyers on trapeze. I also spent a week in the Shubert archives in New York City where I found publicity materials and business records of my relatives’ experience working for the Shuberts. The greatest boon to my research has been the Internet where I have found countless additional newspaper articles about the pair, including photos in the Smithsonian online archives. Personal autobiography and personal familial biography is also woven through the show. I have also spent extensive time over my life through both formal interview and informal conversations mining my mother’s and my aunt’s memory of their father and aunt. Consequently, while Lost Lines is in large measure about a journey of discovering the long-lost professional lifestory of my grandfather and great aunt, the show is necessarily about my relationship with my mother and the sense of impending loss that attends on her advanced age.

Production Concept: In this performance I employ stories from my family to explore the lingering effects of irrevocable loss. Through the story of my grandfather and great aunt’s immigration and professional life, the personal trauma of my grandfather’s early death, and my relationship with my mother, I weave a story which hinges upon the experience of what Marianne Hirsch has called post memory. Hirsch distinguishes the concept of post-memory from the allied yet distinct concept of rememory as posited by Toni Morrison. Both rememory and post-memory “account for varying degrees of coming to terms with or gaining distance from the past” (Hirsh “Marked by Memory,” 74). Hirsh notes that whereas Morrison’s “rememory” is “communicated through bodily symptoms, becomes a form of repetition and reenactment,” post-memory works through indirection and multiple mediations (74). “Rememory is a noun and a verb, a thing and action…” (74). Thus as family members of one generation tell stories of the past to another, they are making rememories while they also do rememory. In Lost Lines, the narratives my mother and her sister, my aunt Gloria, told me in interviews form one set of rememories. The archive I have amassed of reviews, and personal and professional publicity photographs form another set of rememories. The effects of post-memory are harder than rememory to track for they are less indexical. Post-memory is the lived material effects upon the living brought about by the events of a distant past. In the show, the tragic and early death of my grandfather was a breach that ruptured the anticipated trajectory of my family and has had knock-on effects that reverberate in my life, even while I never had the opportunity to know my grandfather. In Hirsch’s terms, how my family has dealt with the loss of my grandfather is an event of post-memory. Post-memory is a familial inheritance; the exploration of it potentially enables re-membering or re-alignment of a broken or fragmentary family trajectory. Lost Lines inquires into how memory figures into personal, familial and national identity and attempts to fathom the inconceivable fact that what was once here is now gone. Through my research I have attempted to track the traces left on this earth of people who once were here, people whose immense physical training and virtuosic abilities thrilled audiences, people whose public life is recorded and remains in the textual and photographic archive but who were never personally in my presence.

The setting for production is minimal: a cremation urn which contains sand, a glass container filled with water, a desk covered with books and photos, a chair behind the desk, and another chair with a table. The principle scenic element is an intermittent stream of still and moving images rear projected upon a screen upstage. These photos and film form the backdrop to the performance. My exploration of the photographs of my family is influenced by Roland Barthes’ Camera Lucida and Susan Sontag’s On Photography. For Barthes’ the photograph is “flat death” (92). The photograph shows us what has been and it “adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead” (9). The photos in Lost Lines allow the ghosts of the past to momentarily reappear. Through these spectral images as we bear witness to them, we are haunted by the past as these ghosts live through us once more. Photographs, as Sontag points out are “an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal” (9). Photographs are “memento mori …. Precisely by slicing out this moment and freezing it, all photographs testify to time’s relentless melt” (Sontag 15). This sense of life’s evanescence is precisely contained within photography and is the central motif of the show.

I am grateful for the support and assistance of many good people who have assisted me in so many ways on the journey of discovering the details of my relatives’ lives and in the creation of this performance. Certainly, without the careful and insightful help of Ron Pelias this show would never have been realized. His deft hand can be felt in the script and in the direction of the performance. Ron Shields who served as my department chair provided institutional and collegial support throughout the development and realization of this work. I received financial support from Bowling Green State University for some of the expenses associated with creating this show and these monies were most gratefully received. My thanks go to Norm Denzin and the International Congress of Qualitative Inquiry and the Department of Speech Communication at Southern Illinois University at Carbondale who each provided venues for performance of the show. I am grateful to Maryann Chach and Sylvia Wang of the Shubert Archives in New York City for providing me access to the archives and support whilst there. Finally, I give my deepest thanks to my mother, Joyce Lockford, for her inspiration and for allowing me to tell our family’s story.

Lost Lines

» watch a video recording of Lockford performing Lost Lines

I have this picture in my head. I see my grandmother, Ruth, my mother’s mother, the second daughter of Anna and Peter, standing there by the edge of the water. I see her there, standing at what is the end of the line for her first husband. Standing, just behind her, is her third husband. Or was he her fourth? Or perhaps he stood next to her. Or perhaps he stood away, back at the car while she went to the edge alone. I don’t know; I wasn’t there.

It’s 1952. She’s 47. Celebrities John Goodman and Roseanne Barr are born; Polly Moran and Hugh Herbert die. Unemployment is 3% and a first-class stamp costs 3 cents.

I see her there, my grandmother, a still figure framed by darkness, framed the way pictures do, both revealing and concealing. Revealing what I know, concealing so much that I can never know. I see her at the water’s edge ready to perform a simple act, to finally make an end, a simple end after so much that was anything but simple.

(I kneel at bowl and pick up the urn)

I see her struggle to open the lid. Closed for fifteen years and grown rusty like a forgotten jar of pickles found at the back of a refrigerator, I see her bang it on a rock. Open, I see her lift it up, ready to pour away all that is left of her first love. Lifting it high, feeling the weight of it, feeling the weight of it in her bones, there in that gesture, feeling his life, his life spent lifting, holding, carrying. Lifting first his sister Zita, my great aunt, the second child of Eugene and Claire. Then, after Zita, lifting, lifting a line of other women dancers who later worked with him. Lifting my grandmother too, lifting her from the obscurity of a Broadway chorus line into a life in Big Time Vaudeville. Lifting. Lifting in his arms his two little girls, their little girls. Their little girls, now grown women, he never knew. Lifting all this until so suddenly, so inconceivably, he was gone. Gone and he could lift no more.

I see her pour him into the water. Pouring what remains of him, pouring it all out. Falling into the water, he is gone. An exile in life is exiled in death. Finally. Gone. All gone, except the pictures in her head. She never saw herself having to come to this place. She always dreamed of a different future. I see her there, seeing how the end of him came and how it changed the course of her life; it changed my mother’s life; it changed my life.

I see myself, standing in line. Shivering. I’m shivering. Standing there in line. I see maybe ten of us little, little girls of four or five or six years old, obedient as we stand shivering in the line. I do not see our mothers. They have dropped us off. They are gone. Gone. I see myself there, standing in that line utterly alone. I see our doom at the end of the line. One by one, at the line’s end, we are lifted into the air by a man we do not know, held aloft for the briefest second and then tossed off the edge. Crying, crying comes from the girls ahead of me. I cry too. It’s all I know to do. I am prodded forward in the line. The crying turns to wailing the closer to the end I get. There is a rhythm to this wailing. Wail, scoop, plunge. Wail, scoop, plunge. Into the cold deep end of the pool we are thrown without a lifeline. Wail, scoop, plunge.

I see he is smiling, laughing really. Swiftly, easily he scoops me up. With a thrust he catapults me out into the air. Whack. My breath is whacked out of me as I smack the surface of the water. Down, down, nothing under me but watery space. Gasp. Fight. I burst with fear. No support. No habits. No rules. Nothing but the capricious weightiness of water. I thrash. Legs do all they know to do. Arms push against weighty water and the momentum of my fall. I see me break the surface. Bob to the surface, water filled lungs, spitting chlorine. People line the edge of the pool, people I do not know. Applause. Applause for nature’s memory in my bones. I see them, this line of eyes and clapping hands. I see they are pleased, righteous.

I am pulled back up to the concrete. I plead, not again. Not again. But again, I am shunted into line to learn again what they want my body to tell me. Wail, scoop, plunge. A rhythm that repeats and repeats until finally, I can break from the line, break from the line and run to the waiting embrace of my mother, who has at last returned to collect me. I see her, the picture of 1962 beauty; blond hair, blood red lips, hourglass figure, and cotton cinch waist dress.

1962. She’s 35. Celebrities Tom Cruise and Paula Abdul are born; Charles Laughton and Marilyn Monroe die. Unemployment is 5.5%; the cost of a first-class stamp is 4 cents.

I fall into the folds of my mother. I feel that support my body knows, always knows, in her embrace. “Why did we come to this place? Promise . . .” I make her, “Promise. Never, never again,” I say, “never take me back here.” And, of course, she never does.

I see her standing in her new house. My 85-year-old mother is wobbly on her legs these days, one hand lightly resting on the vanity table beside her to steady her stance. After four hip replacements, two knee replacements, and now a partial shoulder replacement, being upright remains her greatest daily challenge.

I plop down in front of her. I plop down on a wooden chair in her new home, a house she just purchased because it is next door to mine. We only occasionally speak of it, this tacit agreement that this will be her last home.

Last year, I moved her, her dog, her possessions by car across the two-thousand three hundred miles from temperate California to inclement Ohio. Into her own house, so that we can preserve our independence, even while we know she is here so I, so I can help convey her to that last stop.

As I plop in the chair, I see my reflection in the mirror on the wall before me. I see the lines that are hardening on my face and I say, “Oh, I’m getting so old.” I lift the skin of my face, lift my face into a forgotten place, I peer momentarily at a face I used to see.

2012. Celebrities Whitney Houston and Larry Hagman Die. Unemployment is 7.9 %. The cost of a first-class stamp is 45cents.

I see a memory form in her mind. Throughout my life, although my grandfather—whose stage name was Naro, my great aunt Zita and my grandmother Ruth were all gone before I could know them, through the tales my mother tells me, I construct the past. Told in fragments across my life, she and I make memories together, “rememories” is what Toni Morrison would call them. Together, my mother and I both do rememory and make rememories, both verb and noun. This time she tells me of time when she was in her late twenties.

After her first marriage failed, she moved from Texas to Utah into her mother’s house. She just bought a new dress with which to begin dating again; she puts it on and runs upstairs to show her mother, my grandmother Ruth, who is sitting at her vanity looking at her reflection in her mirror. Upon seeing my then youthful and exuberant mother, Ruth says, “you are so young.” After my mother has told me this story, she says, “So, just as I’m remembering that time with my mother, one day you will remember this moment with me.” We say nothing, but she means, a day when she is gone.

Click. I take a snapshot in my mind of this moment. I want to preserve it, to freeze it, to be able to take it out and to hold it down the line when there will be nothing left but this.

This memory.

When we get to the end we must fall or jump. Fall or jump. Fall and Jump! Jump!

He didn’t jump. So she fell. I see her standing there, my grandmother, Ruth. A silhouette outlined in the dim light of night. A phone to her ear. Her daughters are asleep in an adjoining room. Her life, her daughters’ lives are on the line. Why didn’t he jump? How could he fall? He never fell. Never. Never. Except this time.

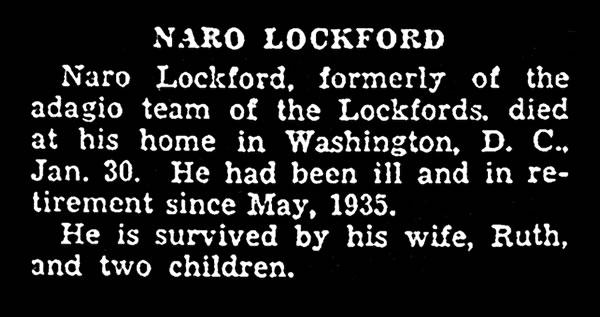

1936. She’s 31. Celebrities Bobby Darin and David Carradine are born; Alexander Pantages, John Gilbert, and Naro Lockford die. Unemployment is 16.9% and the cost of a first-class stamp is 3 cents.

She always liked this act, the one where he put on a funny wig, dressed like a girl and got thrown around the stage by three big men. He always took the audience’s breath away as he stopped just short of the edge with every throw. It was simple geometry. He said. Geometry and physics. He understood geometry and physics.

He was always making things, designing things: patterns for costumes he’d sew himself, a fountain for the backyard, patents for new automobiles and also for a device that would stop the car from skidding out of control. He understood geometry and physics. But this was something he couldn’t control. One of the men threw him off the line and he went into the pit. His last performance. He fell off the stage, came back to the family home in Washington DC, got sick, and died.

My mother is eight and her sister is ten. Probably it’s cancer, but in hushed voices as he lay on the living room settee getting sicker and sicker, they all say it is because of the fall. After a career of headlining in all the best theatres across the country, as talkies became the rage, he was reduced to playing for what he called “peanuts.” Vaudeville was dying; so was he.

“He’s gone,” the voice on the line says. And with that word, the future she dreamed of is swept away. She was then left completely alone in the world to raise her two little girls. My mother says, she heard the phone in the middle of the night, then the sound of her mother wailing as she fell to the floor.

(Cue: Music—Swan Lake) (Cross DL – I leap and do various ballet moves across the stage)

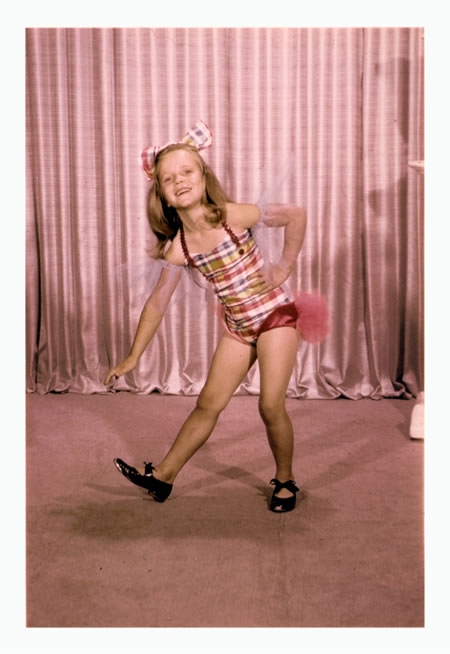

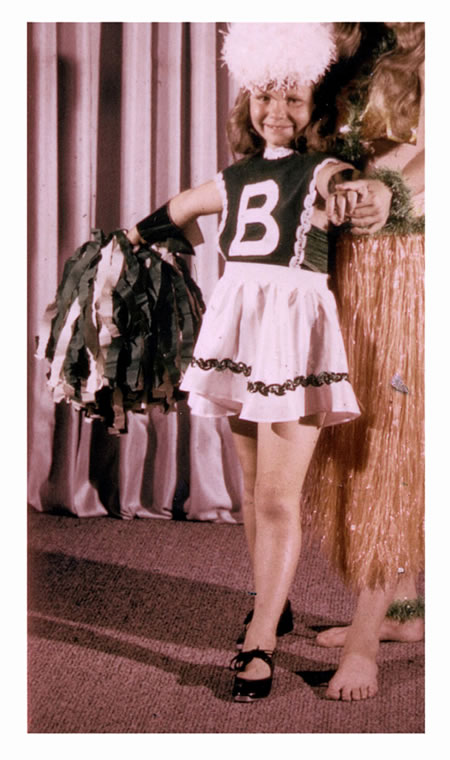

At the age of 8 I could jump better than anyone. I soar. I leap and I land with what I think is grace. I am the greatest dancer in the world! I am the star on the stage of our living room carpet. “Mom! Mom! Watch me, Mom!” I fly across the carpet. “Mom!” “Mom! Come here!” (To audience) I’m her daughter. It’s her job to watch me. Every leap is better than the one before. “Mom! I can’t wait for the commercial! Come here now! . . . Mom! Watch me!” And, of course, she does. I see her sit on the couch and watch me jump and leap across the room. Annoyed at having the ballet she’s watching on TV interrupted, but duly doing her duty, she says, “Marvelous!” as she stands up and applauds on her way back to the den to watch TV. Always my best critic! I know in my bones I want to be a dancer.

So, of course, she enrolls me at the Rosalie Stubbs School for Dance where I tap my little heart out. We prepare a recital for our moms. I’m so nervous.

(As the following occurs, I tap out a routine in the deliberate manner of a child doing a tap dance and speak the words in rhythm to the routine)

A line of girls in cheerleader costumes, we tap out “I Want to be a Football Hero” as a solitary little boy, maybe four years old, punts a football out into the audience very badly. A row of ten of us girls tap behind him. It’s our recital, but he is the star. We are the chorus line. And there’s my Mom. Right there. Right there in the front row, watching me. (Tap routine ends) For her, I’m the star. We take our bows. As we disperse and gather up our things, she hugs me tight and, of course, tells me, I am the best one. I am, of course, absolutely awful. Never could dance. But, “Mom,” I say, “I am made to be a dancer!” She says, “Of course you are, Honey, ‘Daddy’ was a dancer?” Daddy? Oh, “Daddy.” Your, ‘Daddy.”

(I draw a hopscotch diagram on the floor with chalk then play hopscotch during the following--jumping over the squares, picking up a token throughout)

Gaps. Always these gaps. And I couldn’t always jump between them. Other people had family reunions. Other people had parents with anniversaries; other people had fathers with big hands, scratchy faces and shaving cream in the bathrooms. No father, no grandparents, all gone. At least in the eyes I see of other people, it all seems a great big gap. But I have my mother, my mother with enough love for me to span any chasm. That’s all I need. I have all that and the stories. “Daddy was French,” she says, tracing our family line. “That means I’m French.” Ooh la la! How did that happen? How on Earth did we get to this place?

(Cue: Music—Buck Owen’s “Streets of Bakersfield")

To this small ultra conservative dusty town on the edge of the Mojave Desert? The huge sign at the city’s edge proclaims it “The Nashville of the West: The home of Buck Owens and Merle Haggard.” It’s a family joke. Another gap: between us and the town. We are never totally at home there. My mother’s dreams of a different future get swept away when Ruth dies at the age of 55. My mother is 31 and I am not yet 2. Another great big gap, but one I didn’t see until much later. She was then left completely alone in the world to raise her two little girls. So the security of her job as a college English teacher buys us tickets and time away from that desert town with its bobbing oil wells, fields of onions and migrant workers, and pastures of roving sheep. We travel. Two ocean voyages and, literally, on our first trip, we drive in a car around Europe for fifteen months and see all the sights. When I return to that dusty town, my schoolmates—whose parents and parents’ parents on both sides had mostly been born, bred, and died there—if they believe my stories and many don’t, can’t understand why anyone would want to follow the jagged trajectory my mother took us on. Why wouldn’t I want to be at home in the place they were happy to call home? A place that banned The Grapes of Wrath from the public schools, and forbade me from doing a six-grade book review of Catcher in the Rye.

I have other books. A secret book. A book filled with yellowing pages and black and white photos. See me crouch on the floor of the closet in my mother’s room cradling this book. I am forbidden to be in my mother’s room when she is not, a fact that makes it all the more magnetic. See me on top of a heaping pile of shoes, stilettos, fur-lined high-heeled boots, fashions from the 40s and the 50s. Dresses with impossibly tiny waists and a huge raccoon coat that fills the closet with the scent of Shalimar are suspended above me. These things no longer fit the contours of the mother I know and they can never be worn in the California heat. See, there are stories in these things. They speak of long gone places in my mother’s past. See, these things have secrets. I turn the pages of this book that I have taken from my mother’s drawer. I crouch on top of the shoes, trying to draw a line in my mind between the pictures I see in the book and the world I know. I search their faces, the contours of their bodies, for something to recognize, to see myself in them. I want to see my mother’s “Daddy” become my grandfather.

See me hold these pictures and see for the first time these “ghostly revenants from an irretrievable past” (Hirsch, 81). They are the shadow lines defining “the irreparability of loss and the pastness of the past” (Hirsch, 81). Illusions, illusions of continuity. I see these ghosts and they look back but they cannot see me. I recognize them, but they can never recognize me. I see them but there is nothing, nothing, but gap. “Flat death” is what Roland Barthes calls photographs (92). It is a haunting. There is no other word for it. Haunting, a word that etymologically has one foot in the word for home and one hand reaching toward the roots for longing. I want to feel these specters on a page move something, move somewhere in my bones. I see them on the page and they are both here and gone. I search the photos for some filament to tug in me, to connect me, if just for a second, from here to there. I search for the look, the sting, that element in the photo that “shoots out of it like an arrow” that will pierce me (Barthes, 26). But for all my searching, there is nothing that penetrates. They are beautiful and other worldly. Nothing there inserts itself into me the way things do when we are moved, when we are punctured by the poignant, like the way you feel when you close a good book. Or the way a lover’s kiss enters you and irrevocably inhabits you. Or like when you see you have hurt someone you love and you see in their eyes that some part of them has shut the door on you, shut the door on you, forever altering you.

I see her slam the door. It’s just too much. It’s just too hard. She doesn’t have anyone to turn to. No one to hold her. No one to hold on to. No one to tell her she did the right things. She thought I was gone. Gone. Forever.

1972. I’m 14. Celebrities Jennifer Garner and Ben Affleck are born; Maurice Chevalier and Miriam Hopkins die. Unemployment is 5.9%; the cost of a first-class stamp is 8 cents.

(Cue: Music—Derek and the Dominoes, “Layla”)

It isn’t the first time I jumped out the window. Jumped out in the middle of the night.

Jumped out to be with friends so I could jumpstart my adolescence in a night of smoking and drinking and hanging out. This time it’s down at a friend’s house, my best friend whose name is also Lesa, down where she lives, down where I am staying for the night, down in that part of town where Lesa knows someone who has a single parent who works third shift. Lesa’s mother, on her way to her bed, checks in on us and finds us gone. I see my mother take the call. A call in the middle of the night, a call that makes her throw on her clothes, check on her oldest daughter, get in the car and drive through the night to wait with Lesa’s mother. They wait and wait, these two mothers of Lesas.

When the first peep of sun hits my face, I can’t believe I fell asleep, fell asleep in the arms of Tim, the first person with whom I fell in love. I jump up, rouse Lesa awake and we run quickly and quietly hoping to reach her home before we are found out. We run with excitement for the night we had and with fear that we will be caught. At her bedroom window, we jump back through as stealthy as bobcats. The house is silent and still. As we get out of our street clothes and into the bed, we are buoyant with relief, relief that we made it before anyone stirred.

Click and light fills the room. Lesa’s mother enters. My mother pushes forward. Face red. Eyes wet. Arms out. She folds me in and the weight of all she’s held in falls out of her, falls over me. Nothing much is said as we leave their house. At the steering wheel, nothing. Just a reach, a reach to me, a reach to touch me, to feel and be convinced through the certainty of her hands once more that I am here. At our house, I see the distance form; I see her eyes avoid mine. I see her walk, walk down the hall. I see her shut the door. I stand outside her door, in my mind I see her face down on the bed, the way I’ve seen her a few times before, other times when the world fell in on her. I scratch at the door. “Mom? Mom?” She says, “Don’t come in. You can’t come in.”

I shut the book. The book is shut away in a box for many years. Still, with every passing year, they haunt. My mother’s stories of her “Daddy” are and cannot be anything but the stories of a child. She can tell me how he liked to make things; how he was fascinated by cars. She can tell me how when he was very ill and she was running around making noise, he lost his temper when she wouldn’t stop and he turned her over his knee. She can tell me how when she was five, Donald O’Connor kissed her on the cheek backstage. She always calls him her first boyfriend. And she can tell me how she was even part of the show when they dressed her up like Shirley Temple and she sang the “Good Ship Lollipop.” She tells me many things. But still between her “Daddy” and the images we see together in the book, we are caught between the archive of still images and the absence of their bodily repertoire. Their silent stillness taunts me, calls to me from across the divide, urges me to bring them home.

Home. “Come home,” she says. Home? Oh, Home. Your, home.

I see myself standing outside the door, a fallen figure, one hand gripping the knob. A coat on my arm, a couple of boxes, a suitcase, and my cat scratching in a carrier at my feet. A journey that led to a career, a marriage, a new nationality, a life built piece by piece over a decade in London can not now support me. Home? A word now as vacant as the flat I am leaving. I’m not tired of London. I am tired of life.

Click. I shut the door, and with that click, the future I dreamed of is swept away. After my first marriage fails, she moves me, my cat, my possessions by plane across the five thousand, three hundred and forty-seven miles from urbane London to suburban Los Angeles, into her house, so that she, so that she can help convey me to a new life.

1990. I’m 31 years old. Celebrities Kristen Stewart and Emma Watson are born; Greta Garbo and Barbara Stanwyck die. Unemployment is 5.6% and the cost of a first-class stamp is 25 cents.

I see myself, in her house, a specter of my former self, dressed only in black. As I lay on the settee in the living room getting sadder and sadder, they all wonder what happened. What happened to the youthful and exuberant woman who followed a dream? At 21 I ran away from home in Los Angeles to London for a life on the stage when, against all odds, I won a place at a prestigious British drama school to train for a professional career as an actor. I get the training, get an agent, get work, get more work, get married. Then, as the years tick by, as the lines begin to harden on my face, the bookings steadily decline.

“Welcome home,” she says. A word she swoops under me like a net. “Stay here, go to graduate school, forget what you lost, find a new life.”

And piece by piece, I do.

I never dreamed of being a teacher; I never dreamed my love of doing performance could get tied to a new love of studying performance. I never dreamed I’d get two graduate degrees, until I did! As I walk in the line and cross the stage, I, of course, see my mother say, “Marvelous,” as she stands and applauds on my way to get my diploma.

Years give way, and what was a personal childhood fascination gets tied to my professional abilities. I reach out to find them, to find a timeline of his life that can tie it all together.

I reach out to find them, and what I find are words and pictures, more words and more pictures. Everywhere I find them, words and pictures. I reach into theatrical archives and libraries. More words and more pictures. I reach for books on vaudeville, and I reach into the archives of the Library of Congress. More words and pictures. And into the Internet I extend my reach and there they are everywhere in online, words and pictures everywhere framing, revealing, and concealing, words and pictures that depict a fragmented story of The Lockfords. Piece by piece I line them all up, these words and photographs of witnesses who captured lived moments I can never know.

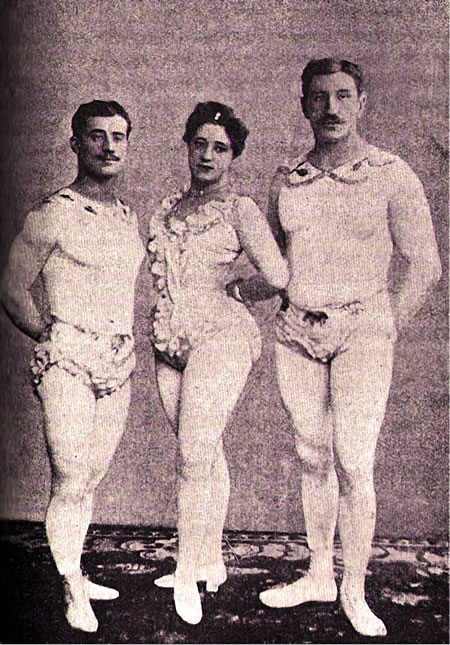

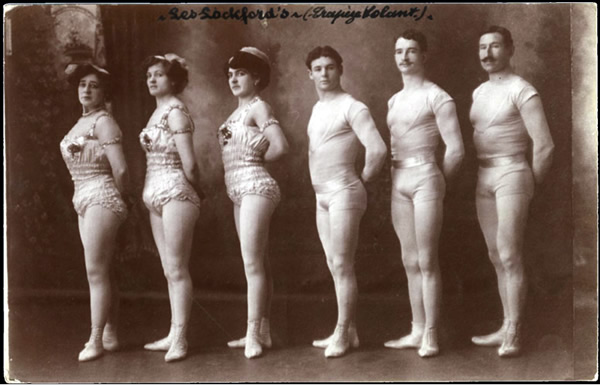

They were born into a theatrical family in the suburbs of Paris.

Their father, Eugene, was a trapeze artist, among the first to “fly” on the trapeze in the late 1880s.

Their mother was a ballerina dancing at all the best houses as well as flying with the family trapeze act. They raised their kids to be dancers, trained them with an iron hand in the dance studio at the top of their house from the age of three. 1921. Naro and Zita are discovered by a Shubert Brothers’ scout while they play at the Folies Bergere in Paris.

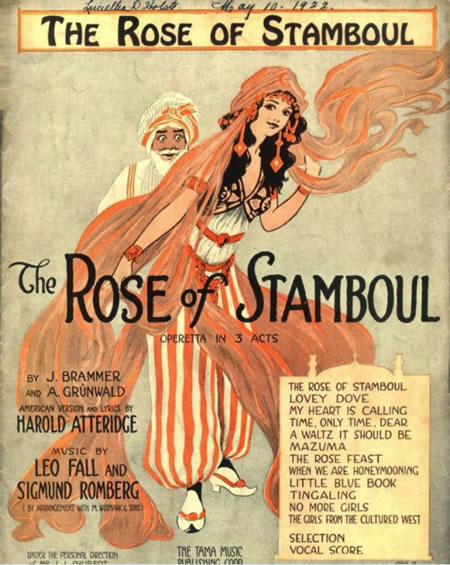

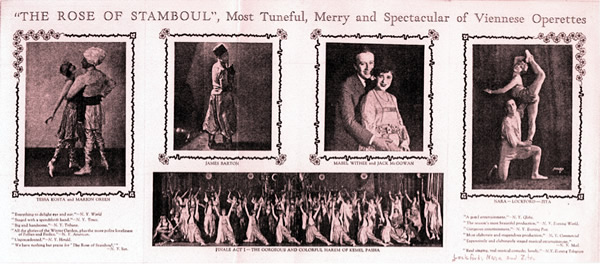

They are brought first class on a ship with their mother as chaperone. They come to a New York City and a United States where immigration and women’s reproductive health are divisive socio-political issues. Warren Harding becomes president on the slogan “less government in business and more business in government.” Prohibition is the law but the illegal use of intoxicants is rampant. A world of factories filled with immigrants seeking a better life, immigrants who fill the vaudeville houses at night. For twenty-five cents they see themselves on the stage in the comic routines that poke fun at their ethnicities. They define themselves and the America they dream of against the exotic and orientalized fantasies realized with exuberant ornateness on the multiple vaudeville stages owned by the Shuberts, Keith-Albee, Pantages, and Orpheum. Unemployment is 11.7%; the cost of a first-class stamp is 2 cents. Press releases announce that the Shuberts buy The Lockfords out of their contract at the Folies Bergere for $10,000 to play at the Century Theatre in a show called The Rose of Stamboul.

The show is okay but the critics call the Lockfords “The World’s Greatest Dancers.” Their mother sails back to France when The Lockfords’ engagement is extended so that they can join the Shuberts’ annual revue at the Winter Garden called The Passing Show, a sort of 1920s version of the Daily Show filled with comedy based on topical issues, but also with music, dance, and blackface.

I show my mother the pieces I’ve found. I line them all up, line them up for my mother. “Look at them, Mom,” I say, “If you read them all, you can see their whole career.”

Mom begins lifting the reviews, one after another, not reading, but looking at the photos. “There are so many,” she remarks.

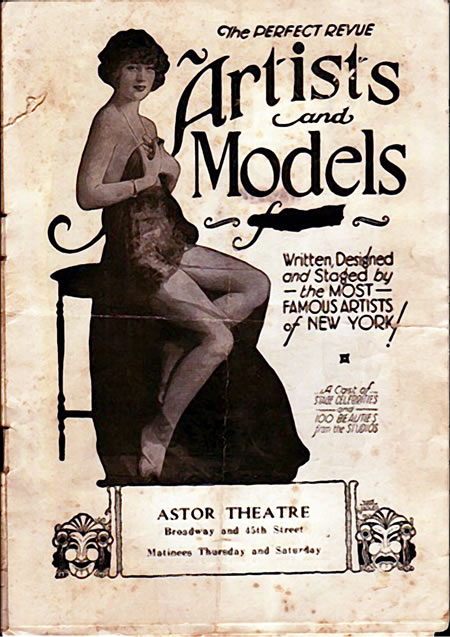

My mother and I piece together a story, we try to fill in the gaps. She tells me, “My mother ran away from home in Washington DC to Broadway when she was 15.” I tell her, “The first show I found with her is in the chorus line of a Shubert revue called Artists and Models.”

She laughs when she sees her mother in the show publicity in a diaphanous dress and sees the skimpy clothing the chorus line wear that somehow passed for “clean” vaudeville instead of dirty burlesque. I tell her Ruth then joined the chorus line of The Passing Show of 1922. My mother says, “Joan Crawford was in that chorus line too. Only then her name was Lucille LeSueur. Momma always told me that Crawford had the hots for Daddy. But he thought she was vulgar.”

Piece by piece, my mother and I read the reviews. Together we string them together into a net and catch the rememories we make.

The Lockfords’ names regularly appear in bold type on the top of the programs.

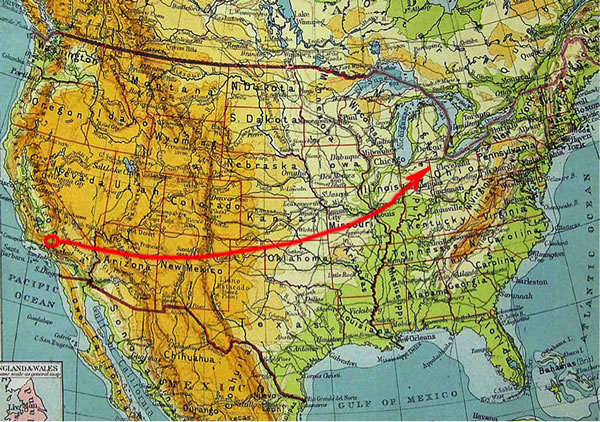

As part of The Passing Show of 1922, on the two hundred and thirty thousand, four hundred and sixty-eight miles of railroad lines connecting the United States, the Lockfords pass through theatres from New York to Raleigh to Pittsburgh to Toledo, to New Orleans to San Antonio, to Seattle to Francisco, and to every city, small and large, in between. They were never dropped by the Shuberts who notoriously cut costs by dropping what they thought were the less essential acts as the show traveled west.

I point to one review from Chicago 1923: “From Paris. Mademoiselle Zita Lockford.

This flaming and exotic young person is among those present in The Passing Show at the Apollo where she indulges with her brother in eager acrobatic dances. The male Lockford is a muscular monstrosity. He flung Zita about as if she didn’t cost a cent.”

My mother laughs and says, “Zita was only 4 foot ten! Daddy was just 5 foot three! Momma always said that Daddy thought Zita got a lot of the attention while he did all the heavy lifting.”

I reach for another: Detroit, 1923:

“The greatest (not one of the greatest) dancing acts that ever graced the stage are on the bill. Language is futile to convey an impression of them. If you can summon to your mind a picture of a fairy enveloped in a cyclonic cloud and whirled hither and thither through flashes of lightning, you will have some approximation. They put into dancing, feats and steps never dreamed of before. They brought the house down in thunderous applause.”

“Look, this one is from Vancouver.” My mother says, “Daddy and Momma got married in Washington State. Daddy’s mother, who was I guess Catholic, you know, disowned him for marrying Momma. I guess, because Momma was American and protestant. Momma said Daddy’s mother always called her, ‘That German woman,’ even though, as you know, her parents, Anna and Peter, were Danish.”

I tell her, Zita and her Daddy left the Shuberts in 1925 and joined the Keith-Albee Vaudeville circuit.

She tells me, “Your aunt Gloria was born in 1925.”

The reviews move from my hands to hers, hers to mine. I say, “Read this” as I pass a review to her. She does, “Sacramento, 1925: Nothing like Naro and Zita have been seen in vaudeville. It is their amazing control and suppleness that gives their act its distinctive turn. Comedy occurs when Naro appears in a Chaplinesque make-up and tries to arouse his loved one, who is dead on the floor. The limpness Zita achieves is almost incredible. Their Apache dance had a riotous joy of living, splendid grace, and thrilled us to the heart. The audience sat breathless during their amazing dance.”

I say, “They did an Apache dance?” My mother laughs, “Oh no, Honey, Series of ‘ApaSHAY,’ not ApaCHE. Apache dances were sort of violent. Lots of simulated knocking the woman about. Like in these pictures,” she points to the photos accompanying the reviews.

I tell her that they played the Palace in New York City at least eight times.

The Palace was the top of vaudeville. All vaudevillians wanted to play there. I tell her that they took 5 bows there, the most anyone ever got at the Palace and were rated number one in Zit’s Theatrical rankings. We see that they then start being billed as “The Marvelous Lockfords.”

“Here’s one from Washington 1926,” “We have a prejudice against people who bill themselves as The Marvelous something—or others, because usually it’s just the other way around. But the Marvelous Lockfords more than justify the adjective. In fact, they suggest new superlatives. Washington has never seen such dancing before.”

I say, “You were born in 1927? When did Zita return to France?” She says, “I don’t know when exactly. She got married to. . . I think Andre was his name. I don’t know his last name. She had a little girl. Momma said the girl’s name was ah. . . ? Monica! I don’t know much more. And then, of course, once the war happened, there was no way to find out.”

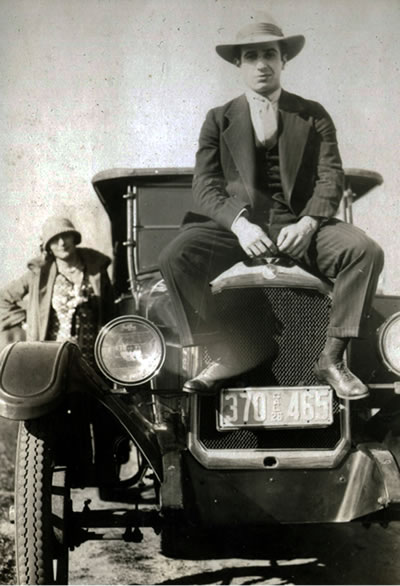

I say, “So once Zita was gone, your father created his own dance company?” “Yes, three men other than Daddy and one woman. From the end of the 20s and into the early 30s, we traveled in the car. Daddy drove, Momma was in the middle of the front seat, the woman dancer was next to Momma. The three men sat in the back seat and I was suspended in a hammock between the front and back seat.”

I say, “So you went all over the country in that car touring the Keith-Albee, the Orpheum, and Pantages circuits.”

I reach for the Keith-Albee contract I found.

“Look, in 1930…that was in the midst of the Depression.” “Yes,” she says.

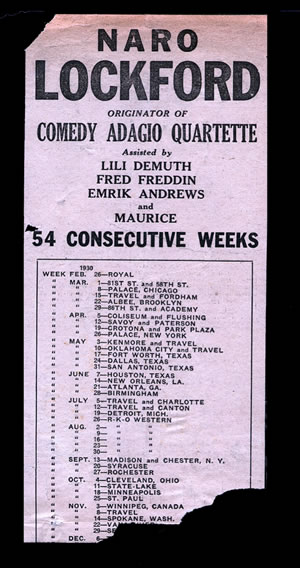

We see that Lockford and Company was booked for 54 straight weeks at $950 a week. But then we see as we look at the reviews that as the years ticked by the bookings steadily declined.

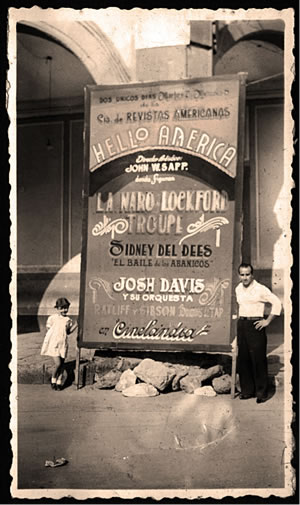

My mother tells me, “I got harder and harder for them to find work. So he got the idea of touring Mexico with the show.

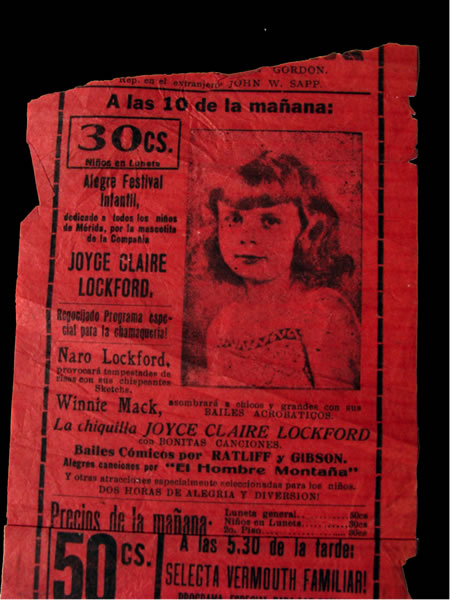

Daddy made all the women dye their hair platinum blond, even the kids, even me.

Blond was the rage then; I guess, they found it especially interesting there . . ? I don’t know.

That’s when I sang in the show, you know, like Shirley Temple.”

They travel everywhere to find work. On the marquis of the theatres he plays, the names of people he once played with side by side on Broadway also appear. Only in these theatres, they are stars and their images are projected larger than life on the screens behind him. He’s thirty-four years old. He falls from the stage, becomes ill, and in January of 1936 he dies.

I show her his obituary that someone cut out and put in the file on The Lockfords I found in the special collections of the New York Public Library.

She tells me, “He was cremated and Momma sent the urn first-class to his mother in France. His mother sent it back, C.O.D. Momma sold all her jewelry, her furs, anything of value. After a few years, your Aunt Gloria was getting married, so Momma takes me by train from DC to California to start a new life.”

I say, “What happened to the urn with your father’s ashes?” She says, “It sat on the mantle in Washington for a few years until it was moved to the garage.”

Where it grows rusty until fifteen years after his death, Ruth comes back to the home in Washington for a visit, and at the urging of her sister to, “Get it out of the garage,” Ruth takes it to the edge of the water.

I see her there. My mother, Joyce, the second daughter of Ruth and Naro, I see her sitting there at a table, at various tables across my adult life. After every journey I make to the archives, to the libraries, to the family home in Washington, to Naro and Zita’s childhood home in the suburbs of Paris where I stood in front of the house where they grew up and trained as dancers, I return home to I tell her of the traces that I have swept together about these people she only sees through the eyes of a child. Together at the table, we pore over the words of witnesses we never knew who saw things we could never see. There are still so many gaps we cannot fill. And, they are still gone. And they still haunt. And though I feel like a ventriloquist of the dead as I tell her the tales I can now tell, tales I have exhumed from the tomb of the archive, I see her eyes brighten.

[note: This reference to being a ventriloquist of the dead derives from Tom Conley’s introduction to and translation of Michel De Certeau’s The Writing of History.]

I see her begin to see them in ways she never did before. In her eyes, I see new memories form. In the delight that we make together, in the laughter that erupts in her, and in our astonishment of all that remains despite how long her “Daddy” has been gone, I see her Daddy come home to her, come home not just as her “Daddy,” but as the man he was.

Click. I take a snapshot in my mind of this moment. I want to preserve it, to freeze it, to be able to take it out and to hold it down the line when there will be nothing left but this.

This memory.

I am standing here, waiting. I can see the end of the line. The end when the last witness will be gone.

It’s two-thousand and . . . I don’t know. . . .

I have this picture in my head. I see me standing at the water’s edge ready to perform a simple act, to finally make an end, a simple end after so much that was anything but simple. (I Kneel and lift up urn. The lid is on it so it is closed) I see I will lift it up, I will lift it high, feel the weight of it, feel the weight of it in my bones, there in that gesture, I will feel her life, her life spent lifting, lifting, lifting me. I see I will pour her into the water. Pour what remains of her, pour it all out. Falling into the water, she will be gone. Finally. Gone. All gone, except the pictures in my head. (I swiftly bend down and put urn back down on floor. I move away upstage of the bowl) I dig down deep and push away that edge that I know is just there on the horizon, an edge that we are surely, inexorably moving toward. I know when I get to that end I will have no option but to fall. I will tumble into the void, freefall and fight to find some foothold. No support. No habits. No rules. In that unmoored space between what was and what will come, I will feel the folly of faith in continuity. There is no point of arrest. There is only another here, another now.

For what is here,

just here,

is then,

just gone.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Richard Howard, Trans. New York: Hill and Wang, 1980. Print.

De Certeau, Michel. The Writing of History. Tom Conley, Trans. New York: Columbia UP, 1988. Print.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Marked by Memory: Feminist Reflections on Trauma and Transmission,” Extremities: Trauma, Testimony, and Community. Nancy K. Miller and Jason Tougaw Eds. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2002: 71-91. Print.

Acknowledgements

Video and Graphic Images Designed by Bradford Clark.

Script Consultation and Direction by Ronald J. Pelias.

Special thanks to Amy Elman, Heidi Nees, JP Staszel, and Angenette Spalink.

Lesa Lockford is a Professor in the Department of Theatre and Film at Bowling Green State University in Ohio. She teaches courses in qualitative inquiry, performance studies, acting, and voice for the stage. Her book, Performing Femininity: Rewriting Gender Identity was published in 2004 in the Ethnographic Alternatives series for AltaMira. Her essays have appeared in various journals including Qualitative Inquiry, The International Review of Qualitative Research, Theatre Annual, and Text and Performance Quarterly.