Introduction

There is more than one scene in the film Dead Man Walking (1995) where Sister Helen Prejean, played by Susan Sarandon, drives from New Orleans to Angola, Louisiana, to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. Prejean makes the drive to visit Matthew Poncelet, a man sentenced to die for the kidnap and murder of two teenagers. The driving scenes in the film serve an explicit purpose; the drive is both transformative and reflexive as it moves Prejean, and the audience, from the “outside” to the “inside” and then back out again. Each scene captures Sarandon’s character deep in thought and lasts longer than is expected of a Hollywood feature film; absent of dialogue and tightly framed on Sarandon’s face--pained by the tensions associated with being the spiritual advisor to a man on death row--the scenes convey the chasm between the “free” and “incarcerated” worlds.

When I make this drive, albeit in much less dramatic fashion, I think about the men and women (visitors, soon-to-be incarcerated men, those being released, and employees) who, for almost two hundred years, have traveled the roads that lead to the Louisiana State Penitentiary (i). There is not much in the way of visual entertainment between the Days Inn in Baton Rouge where I am staying for the weekend and the prison. Signs along Route 61 tell me this is a “Scenic Highway,” but I am not sure why; the landscape is barren and underresourced. Few drivers are on the road at 7:00 on a Sunday morning, so I lean out the window and snap some pictures of the formerly grand plantations homes that dot the highway and advertise “antebellum home” or “swamp” tours and of the empty stretches of highway I am about to pass over; I shoot a few minutes of video, too. It does not take long to realize that making pictures and capturing video while driving distorts my depth perception, but the process of “data” collection is a welcome distraction. Today, on my first visit to the prison, I am consumed by the feeling that I am lost.

Forty-five minutes into the drive, somewhere along Highway 66, I find reassurance in the line of cars that begins to form behind me, and the trickle of cars that I catch up to in front of me. The procession lasts another fifteen miles until we all dead end at the front gate of the Louisiana State Penitentiary. It sounds a bit cliché to say, but the prison is the last stop on Highway 66. The main gate to the prison is fifty-four long miles away from Baton Rouge. We have all made the drive for the same reason, to participate, as tourists, in the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair.

Twenty cars are line-up ahead of me; in the rearview mirror it is difficult to see the end of the traffic jam building beyond the entrance to the prison. We all sit in our cars and wait another thirty minutes before we are permitted onto the grounds of the prison. Ten thousand tickets, at a cost of $10.00 each, are sold for the rodeo, the maximum capacity for the stadium. The crafts fair is free and not limited to a set amount of visitors. The popularity of both events illustrates our contemporary culture’s fascination with crime and criminality. Penal tourism is a rapidly growing industry in the United States, undoubtedly an offspring of the success of television crime shows and feature films about the prison system (ii).

Since 1869, Angola has served as a prison warehouse for the Sate of Louisiana. During Reconstruction every man and many women convicted of a crime in the state was turned over to Major Samuel Lawrence James, who created his own penal colony on the former “Angola Plantation,” which the James family purchased for $100,000. Once the Angola Plantation, the 1,8000 acre prison farm, approximately the size of Manhattan, still bares the name of the African region where most of the slaves who worked the land were taken from. A significant portion of the men and women serving time at Angola were incarcerated because of violating the infamous “Black Codes,” the southern laws that limited the freedoms of emancipated black men and women (iii). By transforming the plantation to a penitentiary the slave economy in Louisiana seamlessly became a prison economy.

By the 1920s, the State of Louisiana had taken control of the prison in response to reports of extensive abuses suffered by the incarcerated men and women at the hands of Major James and his family. Since the time of the state’s intervention until well into the 1970s, the prison experienced cycles of reform and repression (iv). One of the most tumultuous times in Angola’s history occurred just before the Civil Rights era of the 1960s. In 1951, a group of thirty-one white men slashed their own Achilles tendons in a desperate effort to bring attention to the brutal conditions at Angola. Known as the “Heel String Gang” this group of men brought temporary change to a corrupt prison system. A food riot, initiated by black men, followed the “heel-slashing” on Easter Sunday of the same year. Both acts of resistance drew significant public and political attention, resulting in the allocation of $8 million to reform the prison, including building a new central penitentiary, expanding educational services, constructing housing separating men and women, and replacing striped uniforms with denim (v).

Change in the prison system is slow and progress is often unpredictable, and in 1965 the prison was again at the center of controversy amid reports of abuse and mistreatment. Known as “American’s Worst Prison” in the 1950s, by the 1960s, Angola was considered “the bloodiest prison in the South” (vi). Since the 1960s, and particularly during the years that Burl Cain has served as warden (1995-present), the Louisiana State Penitentiary has been a glaring representation of the nostalgic approach to discipline that has prevailed in the southern United States. On this working farm the incarcerated men spend their days tending fields of soybeans and cotton. They transport goods around the prison in mule-drawn carriages, often outfitted in striped uniforms. Angola is just one example of why southern prisons have historically been considered some of the most backwards in the country. Robert Perkinson, in studying the history of the plantation-to-prison model, argues that “dehumanization and popular vengeance” became the “selling points of a new punishment order” in the years immediately following the end of the Civil War; a tradition still present in many contemporary prisons (vii). The Louisiana State Penitentiary is a contemporary remnant of the plantation-to-prison system that spreads across the landscape of the southern United States. The history of the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola is put on display in the Angola Museum, located just outside of the gates of the prison.

The emergence of the prison rodeo as a popular form of entertainment, situated in a tradition of brutality and dehumanization, is part of the history of many prisons throughout the south (viii). Few maximum-security prisons in the United States continue to host “prisoner-run rodeos,” and only Angola offers an “inmate-produced” arts and crafts festival. Research access to the event was granted to me by prison administration. Although I never had direct contact with Angola’s Warden, Burn Cain, I understand enough about the administration of a prison to know that he was the final word in granting my access (ix). Situated within the context of current crisis of mass incarceration in the United States, part of which is a crisis in representation, the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair exists as an embodied performance of discipline in the “theater of punishment” in the United States (x). The United States incarcerates it’s own citizens at alarming and unprecedented rates. According to the most recent findings reported by the Department of Justice, 2.3 million men and women in the United States are incarcerated--1 in 100 adult citizens are in prison or jail and 1 in 31 adult citizens are under some form of state supervision (prison, jail, parole or probation). More than 50% of the men and women incarcerated in the United States are black and close to 10% are Latino. No other country in the world comes close to matching the United Sates’ corrections record (xi). Because few prisons throughout the United States are open to public participation a culture of silence and fear defines most non-incarcerated citizens’ relationship with the prison system. Events such as the Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair offer the possibility of opening up the space of silence. This essay explores what happens when the often hidden space of the prison system is made public.

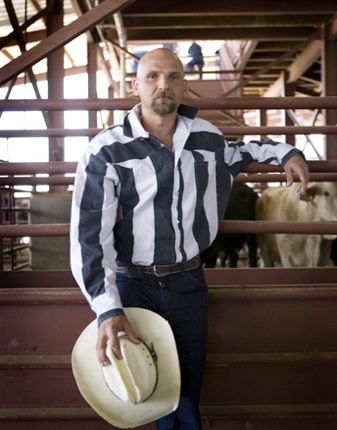

According to the Angola Prison Rodeo Charter, the event was originally established in 1965, to provide “recreation for the inmate population and entertainment for employees,” and the gates to the rodeo were opened to the public two years later. Very quickly the financial success of the rodeo was realized, and in 1969, a 4,500-seat arena was built on the grounds of the prison. In 1997, the arena was expanded and three years later, as attendance continued to grow, the stadium was again rebuilt. In 2000, the men at Angola built a 10,000-seat rodeo stadium. Initially, the crafts fair was a separate enterprise, but in 1997, it was combined with the rodeo to provide visitors with a daylong festival. It is primarily the “lifers” who run, organize, and participate in the rodeo and crafts fair events, and it is these men who are able to mix and mingle with, sell hobby crafts to, and prepare food for curious tourists from the “outside.” The crafts fair features thousands of pieces of art, referred to as “hobbycrafts,” made by “jailhouse artists”; the rodeo, the more controversial of the two events, puts untrained “inmate cowboys” into the rodeo ring.