Eight Hours Behind the Razor Wire

Precisely at 9:00 a.m. the first car is waved through the single entrance to the prison; the procession of cars that follows moves slowly. The interior of each car is visually inspected and the passengers are informed of the rules that govern the day. The slightly graying, white, male corrections officer that bellies up to my rental car tells me that I must leave any weapons, ammunition, alcohol, and drugs at the gate. Additionally, the man in the monochromatic blue uniform instructs me that any food, ice chests, pocketknives, medication, toolboxes, cameras, video cameras, and cell phones must remain locked in my vehicle. As a last line of defense, I am handed a list of rules on a half-sheet of paper; the same rules I was told moments ago. It is clear that my compliance with the rules of the event is vital to the efficacy of this performance. “Lock your vehicle” are the last words I hear as I begin to slowly drive down the two-lane road that bisects the main campus of the prison. Upon entering the prison it is evident that the aesthetic of pre-Civil War America is not lost. Fields of soybeans and cotton line the entry to the prison and are worked daily by crews of incarcerated men, most of whom are black, overseen by guards on horseback, most of whom are white. Established in 1868, the prison grew up during a time when white supremacy was custom and law was dictated by the Black Codes. Historically, Angola is one of the most dangerous prisons in the United States, but it’s a designation the prison is attempting to shed.

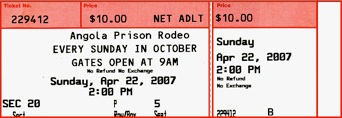

Every Sunday in October and for one weekend in April the prison hosts the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair, commonly known as the “Wildest Show in the South.” The event is marketed as an opportunity for tourists to witness “untrained convicts roping and wrangling livestock” and the opportunity to browse among “authentic prisoner-produced” crafts and concessions. Attracting more than 70,000 tourists a year, the event is big business for the prison, the men currently incarcerated at Angola and the surrounding community. Prison administrators view the event as significant to the “health” of the prison. Yet, at Angola, more than 80% of Angola’s population of 5,000 men will die within the prison’s gates. The Louisiana State Penitentiary is rich in contradiction. Once a plantation, then the most dangerous prison in the United States, the prison farm is now a tourist attraction. In part, my visits to Angola are driven by an interest in seeing how, or if, the history of Angola is represented at the rodeo and crafts fair.

I park my rental car in a seemingly endless field. Because the prison is bordered by the Tunica Hills and the Mississippi River, which form a natural perimeter to the facility, security fences or barricades do not obstruct bucolic panoramic views. The early morning hours at Angola are serene. Less then fifty cars are lined up in neat rows; by the end of the day it will be almost impossible to see even a small patch of grass poking out between the rows of cars. The SUVs and pick-up trucks I park besides, all with Louisiana license plates, dwarf the Dodge Neon rental car I am driving. Early in the morning, before the bulk of the crowds arrive for the main event—the rodeo—most of the cars are local. I assume that many belong to prison employees; I am told that most prison employees will work at least a few hours during the event. Later in the day, when I return to the parking lot to drop off some of my recording equipment, I notice a few license plates from surrounding states (Mississippi, Texas and Arkansas); still, most cars have Louisiana tags. I pack up my equipment and head to the entrance. Because I am permitted “media access” I am allowed to carry a video camera, still camera, and audio recorder, along with my notebook. The “general public” is more limited in the items they can carry into the event (xii).