1:00 p.m.

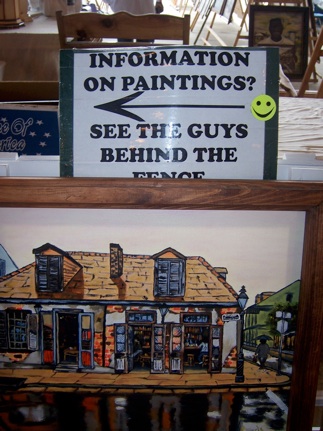

The non-trustee section was described to me by one tourist as “the place where inmates did the leering and other less civil things.” In this area tables are neatly arranged along a towering chain-link fence. On the other side, men line up side by side, watching closely as potential customers pick among their products. Because of the distance between the artists and the consumers, “cat-calls” are the primary mode of communication. Many tourists admitted to me that the space felt “aggressive” and “intimidating,” especially when contrasted with the area where trustees sell their crafts. For Cynthia, a first-time tourist at the event, this section made the experience more authentic. As we stood on the outskirts of the non-trustee area we had a brief conversation. “How do you feel about spending the day on the grounds of a prison,” I ask. She takes a moment and responds, “I understand that there are some safety precautions that must be taken when you are at a maximum security prison. I wish these safety measures, you know, the guards and fences, wouldn’t have been so apparent.” Quickly, she continues: “But, then again, this constant reminder makes it more real—’un-Disney-like’.” I nod my head showing that I agree with her, “it sure isn’t Disney,” I say and before I can respond further Cynthia, along with her husband, whom she introduced me to moments before we began talking, begin to head in the direction of a man selling wooden outdoor furniture. Our conversation ends here.

If there were any guilt associated with the experience of being a tourist at a prison, the non-trustee area would be a likely place for it to be exhibited. The divisions between “freedom” and “incarceration” or the “inside” and “outside” world are so clearly marked in the non-trustee section. This is the place that a tourist might question the practices of mass incarceration as they come face-to-face, through the physical division of the fencing erected for the event, with the reality of imprisonment. In my conversations with tourists, as exemplified by an exchange with Cynthia, I did not find that guilt shadowed the experiences. Fear and uncertainty played a more significant role. I observed many tourists attempting to avoid eye contact with the men and their objects as they quickly moved through the non-trustee area. As Emmanuel Levinas reminds, sharing eye contact (gazing into the eyes of another) forms a bond or sense of responsibility between the two individuals. A shared gaze, in the spirit of Martin Buber’s pronouncement of the I-Thou relation, is not the experience of the tourist or the incarcerated.

The non-trustee area best reveals the desperation of the prison system. In the space where the exotic “other,” standing behind a fence, is put on display, marks the bodies as objects to be viewed and made meaningful by the gaze of the tourist (xxxviii). Margaret Olin contends that the gaze encompasses issues of desire and control, “the desire for self-completion through another” and the desire to be “the master of the gaze” (xxxix). In the space where non-trustee artists sell crafts the tourist is also subject of the gaze. Here, tourists and the incarcerated men are both on display. The men behind the fence see “freedom,” in the form of the tourist’s mobility, moving before their eyes. The non-trustee is the embodiment of discipline, presented as a spectacle and object of surveillance for the gazing tourist. The power in this visual exchange resides with the tourist who is free to leave the space and to not return the gaze. The space where the non-trustees sell crafts is the “battleground” of the gaze that Jean-Paul Sartre describes as the place where the self is defined and redefined (xl). As the incarcerated men and tourists exchange gazes, the freedom of the non-incarcerated visitor is confirmed at the same time that the confinement of the incarcerated men is reinforced. Like the third world bodies that spectators and academics travelled to gaze upon, the incarcerated (trustee and non-trustee) body is the object of the gaze because they are viewed as exotic by the tourist and as a result appear timeless, apolitical and absent of a personal history. The non-trustee area leaves little doubt about who is “free” and who is incarcerated.

In the theater of the Angola Rodeo and Crafts Fair the men behind the fence are props used to illustrate success and failure. Tourists visually witness the successful “rehabilitation” that occurs at Angola when they experience the non-trustee behind the fence juxtaposed with the mild-mannered and polite trustees that require limited supervision. The non-trustees perform the role of the “dangerous criminal” and reinforce the idea of a hierarchy within the prison system. The trustees are positioned as refined in comparison to the non-trustees. The trustee/non-trustee dyad not only serves a function in the penal education of the tourists, it also has an effect on the incarcerated men (trustees and non-trustees). The non-trustees, from behind the fence, face, literally and figuratively, the perceived freedom of the trustees. The trustees remain within eyesight, yet out of reach for the non-trustees. For the trustees the non-trustee remain in the periphery as a constant reminder of where they once stood.

Many of the trustees I spoke with remember their days behind the fence. Emille tells me that his time selling from behind the fence was not as lucrative as it is now that he is a trustee. Looking in the direction of a large row of non-trustees, he tells me, “Behind the razor wire I cannot talk to people. I have to holler at them through the fence to make a sale. They [tourists] look at us like ‘man, they’re behind the fence. What are they? Why are they there? Why are the other inmates over here?’” Jim, who is also a trustee, has a similar impression of the men behind the fence, but he also has the empathy that the tourists lack. As he stands at his table which is in close proximity and clear sight of the non-trustee area, he tells me about the difference between the men behind the fence and himself: Listen.

Though it would be beneficial to the tourist, sharing Jim’s insights would break the frame of the performance of the “controlled” versus the “dangerous” body. By exhibiting tamed and controlled men positioned against a backdrop of men still deserving discipline, the warden shows rehabilitation is working for some men, but not to the extent that reintegration is possible. Jim also reflects the resignation I heard in the voices of many other men incarcerated at Angola when he suggests that the best a man can do is hope to be on the other side of the fence in 23 years. The civility of “well-mannered inmate” on display for public consumption is a theme that carries throughout the crafts fair; the rodeo, on the other hand, offers up the bodies of the incarcerated in the timeless performance of public discipline. Humanity is lost in the second half of the day when “Inmate Cowboys” perform to the cheers and amusement of the rodeo audience.