Setting the Stage

My first trip to Angola was driven by curiosity. I returned for two more years to gain a better understanding of where the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair fits in the discourse about the prison system in the United States. After my first visit to Angola it became clear to me that the rodeo and crafts fair was a particular type of cultural performance, one that both permits and prevents access and understanding. This study critically examines the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair as a performance space that shapes and defines the meaning of the prison system in contemporary culture. In this study I employ ethnographic methods: interviews, participant-observations, and surveys to answer a number of questions about the cultural performance staged at the rodeo and crafts fair. Some of the questions that guide this critical analysis include: How is the prison system perceived when it is staged as a tourist attraction? What is the significance of the role of each of the actors in the performance of the prison as a tourist attraction? What meaning(s) do currently non-incarcerated citizens attach to the prison system when it is experienced as a tourist attraction? What narrative(s) do tourists engage about their experience (during and after their visit) that uphold or challenge status quo notions about the prison system? Do tourists use the experience of participating in the rodeo and crafts fair as means to uphold or challenge the politics of incarceration?

I situate the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair as an element in the social drama of crime. Victor Turner’s model of the social drama might be one of the most fitting lenses to examine the phenomenon of crime in a highly mediated and technologically advanced culture. Turner defines the social drama as “aharmonic or disharmonic social process, arising in conflict situations,” enacted through a process of four stages: 1) A breach of norm-governed social relations occurs; 2) A crisis phase where representatives of order (including citizens) are dared to grapple with the breech; 3) A phase of redressive action ranges from personal advice and informal mediation or arbitration to formal juridical and legal machinery; and 4) A phase of reintegration of the disturbed social group occurs or recognition and legitimation of irreparable schism between the contesting parties occurs (xiii). Turner’s matrix has “crime” written all over it; an individual enacts a breach of a social rule (breaks the law); the breach is addressed and the crisis is made public (a trial is conducted); if found guilty, redressive action is taken (the offender is sentenced to a period of punishment/rehabilitation); and finally, depending on the success or failure of redress, either the offender is accepted back into the community (parole/probation) or continues to be shunned (incarcerated).

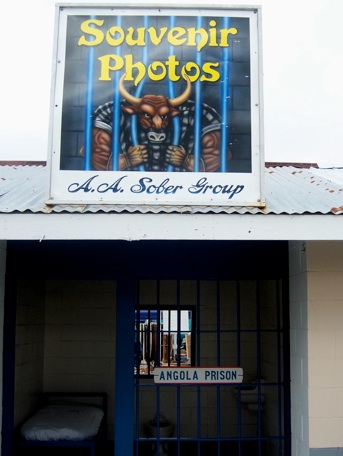

In contemporary culture, the public phases of crime—arrest and trial—are played out in various degrees in the media (print, on-line and/or televised), depending on the “celebrity” of the crime or the individuals involved. Non-incarcerated citizens are permitted access, via technology, to many aspects of the first half of the criminal process. The second half of the equation—redressive action and reintegration—are more secretive events. Yet, at the rodeo and crafts fair the invisible is on display. In the everyday lives of non-incarcerated citizens the prison system is geographically and ideologically removed. In contrast, reports of crime/criminal activity and the judicial process consume disproportionate amounts of space in the media landscape. The Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair challenges the secrecy of the latter phases of the social drama by permitting non-incarcerated citizens access to the phases of redressive action and reintegration. As such, the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair provides a relatively unique experience because it offers an opportunity to engage a critical ethnographic study of the phases of redressive action and reintegration.

This study attempts to practice what Nick Trujillo contends is the task of critical ethnography, “to uncover the power relations which influence how various people, including researchers, interpret culture” (xiv). Following McCall and Becker’s mandate that “ethnography must be consciously ideological” this study addresses the ideological struggles over meanings that emerge from the experiences of tourists at Angola, such as: how do issues of “freedom”, “discipline” and “justice”, get represented in the performance of the rodeo and crafts fair (xv). Because mediated representations, such as the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair, play an important role in the penal education of currently non-incarcerated citizens, understanding the range of meanings that emerge from this experience might provide insight into the reasons why non-incarcerated citizens remain relatively silent about the exponential and unprecedented growth of the U.S. prison system. I traveled to Louisiana to situate myself in the story of the prison system that is staged during the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair. I continued to return to the event because I wanted to ask questions about the meaning(s) of this event for tourists (non-incarcerated citizens) and how the event supported or challenged what they knew about the prison system in the United States.

It made sense to approach the rodeo and crafts fair, as cultural events, through the lens of performance studies. As a project of critical (ethnographic) investigation there are clear connections between ethnographic methodologies and theories of performance. I draw from Diana Taylor’s The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas to create a framework for the study of the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair as a project of critical ethnography and performance studies. Taylor’s work brings recognition to the value of embodied practice as a process of transmitting meaning and shaping cultural knowledge. In contrast to the written “archive,” the performance or repertoire, in Taylor’s work, is the site where “people participate in the production and reproduction of knowledge by ‘being there,’ being a part of the transmission” (xvi). Taylor argues that the repertoire—performances, gestures, orality, movement, dance, and singing—although devalued in Western culture, has as much power to shape cultural knowledge as the text-based archive. Because the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair is almost completely absent of archival resources, the experience of the tourist and the efficacy of the performance rely solely on the repertoire (xvii). Taylor’s privileging of the repertoire over the archive, although debatable (xviii), is well-situated as a framework to understand an event such as the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair. Similar to Dwight Conquergood’s contention that “performance is a site of struggle where competing interests intersect, and different viewpoints and voices get articulated,” Taylor’s understanding of repertoire performance is based in the relationship between knowledge and presence and the struggle over meaning that occurs in the process of “being there” (xix).

Taylor contends that it is through an investigation of the scenario, a term explicitly linked to theatricality, that it is possible to begin to see the “socially agreed upon plot line that underscores popular myths and cultural lore,” which is innate to any culture. Theatricality, in this context, Taylor suggests, reflects the “constructed, all-encompassing sense of performance” (xx). Taylor focuses on the “theatricality” of an event as a way to—relying on the work of Guy Debord in Society of the Spectacle--“highlight the mechanics of spectacle” that frame any public performance. This essay demonstrates, through the reflections of tourists and my own participant-observation, that the performance showcased at the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair is rooted in a particular performance of the spectacle of discipline. As defined by Debord, the spectacle is not an image—although it does have visual qualities—but a “social relation among people, represented by images;” the spectacle serves as a unifying force, often serving as a point of reference for individuals as they form an understanding of their culture (xxi). In other words, spectacle is not simply a form of entertainment; the spectacle influences how individuals see themselves, and how they experience the world around them. In the context of the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair, the spectacular presentation of discipline staged for tourists contributes to the shaping of a collective consciousness about the experience of incarceration in the United States. The spectacle serves to mediate the relationship between individuals and contributes to the identity formation of “me” and “not-me.” At the rodeo and crafts fair the incarcerated men play the traditional role of the dangerous “other;” the tourists are the law-abiding judge and jury.

In order to fully account for the workings of the scenario (repertoire performance) Taylor provides a six step process of cultural investigation; the task is to “recall, recount, or reactivate” the scenario, to “wrestle with social constructions” in order to “understand the framework” that supports the meaning of an experience. The end goal is to “transmit” the scenario through “writing, telling, reenactment, mime, gesture, dance, and singing” (vvxii). I settle upon a combination of textual and multimedia representation for this essay; mime, gesture, dance, and singing are beyond my skill set. Taylor’s guidelines are the map I use to approach a study of the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair; this approach provides a sense of security as I venture into an unknown performance space. Throughout my experience I make an effort to treat every encounter with tourists, currently incarcerated men and prison employees as an opportunity to experience and witness the meaning-making process that occurs as a result our collective participation in the performance. My effort in this essay is to avoid simply “translating” the experience and instead to draw upon my sensory observations, by reporting upon the sights, sounds, smells, and texture of the Angola Prison Rodeo and Crafts Fair.