http://liminalities.net/2-1/sdcp/sdcp1.htm

Social Dramas and Cultural Performances:

All the President’s Women

by Elizabeth Bell

ABSTRACT: Victor Turner’s social drama is exemplified in the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, a two-year saga that captivated the American media, government, and public from 1998-2000. The social drama, with its stages of breach, crisis, redress, and reintegration, however, tells only half the story. Concurrent to the drama, a running metasocial commentary occurred on the Internet in the form of “Monica and Bill” websites, replete with thousands of jokes, graphics, and parodies. This essay analyzes these cultural performances for their perpetuation of hegemonic masculinity and rescue of heternormativity through the President’s women—Monica Lewinsky and Hillary Rodham Clinton. The social drama and the cultural performances that mirrored it on the Internet serve phallocentric social and political orders.

Victor Turner defines the social drama as "a sequence of social interactions of a conflictive, competitive, or agonistic type" (33), and he delineates its stages as breach, crisis, redress, and reintegration or schism. More simply put, the social drama begins when a member of a community breaks a rule; sides are taken for or against the rule breaker; repairs—formal or informal—are enacted; and if the repairs work, the group returns to normal, but if the repairs fail, the group breaks apart. Each time I have taught Turner’s social drama in my graduate Performance Theory class, I have been blessed and cursed with timely exemplars: the O.J. Simpson murder trial, the Clinton-Lewinsky scandal, and the September 11 attacks on the United States. If Turner’s explication of Ndembu social life or the Brazilian Umbanda was distant to my students and me, then the social dramas unfolding around us made Turner’s theory and analysis come alive.

But it is another September 11 that prompts this analysis. Only in retrospect and with no small amount of irony, do I recall that on September 11, 1998, the U.S. House of Representatives released the Starr Report to the public. Eight months before, Monica Lewinsky’s name first appeared on Matt Drudge’s internet website, the Drudge Report, and media frenzy in the intervening months whipped the public’s appetite for the details. On September 11, 1998, these details, in 2,600 pages and eighteen boxes delivered to the House of Representatives, were uploaded into cyberspace.[1]

Seven years later, it’s difficult to remember the media frenzy, and even harder to grasp our two-year cultural fascination with Bill Clinton’s sex life.[2] But I’d like to imagine Victor Turner—back from the grave—having a hay day with MonicaGate as the textbook case of his theory of the social drama. The antagonists were “star members” of their groups, the breach was sexual and salacious, no group escaped side-taking and meaning-making in the crisis phase, and the drama’s redress, an impeachment trial in the U.S. Senate, was—to say the least—historically monumental. Democrats and Republicans shook hands afterwards in the rotunda of the Capitol Building in a “Kodak moment” for Turner’s notion of “reintegration.”

Communication scholars have utilized the lens of Turner’s social drama to explicate events as varied as the 1984 Winter Olympics (Farrell), anniversaries of John F. Kennedy’s assassination (Berg), and Detroit auto worker strikes (Fuoss) for the ways that narrative and spectacle are organized in and around the phases of the social drama. But the social drama is only half the story; Turner expends just as much effort in his works attending to cultural performances born out of the social drama. That is, social drama is the “raw material” for performances that reflect critically on the content of that social interaction. Turner utilizes a linguistic analogy, the “moods of culture” to characterize social life as moving between the indicative (“it is”) and the subjunctive (“may be,” “might be,” even “should be”). For Turner, “A social drama is mostly, at least on the surface, under the sign of indicativity. That is, it presents itself as consisting of acts, states, occurrences that are factual, in terms of the cultural definition of factuality. Every culture has a theory that certain ‘things’ actually happen, are ‘really true,’ that ‘have been’ or ‘are’” (41). “Most cultural performances,” Turner argues on the other hand, “belong to culture’s ‘subjunctive’ mood.’” Ritual, festival, carneval, folk stories, ballet, staged drama, novels, epic poems—a multitude of culturally recognized genres—are drawn from the “raw stuff” of social drama. Most importantly for this analysis, Turner claims that “what began as an empirical social drama may continue both as an entertainment and a metasocial commentary on the lives and times of the given community” (39).

The Clinton-Lewinsky saga is exemplary of the interplay between indicative social drama and subjunctive cultural performances. Richard Schechner (Performance Theory) describes this interplay as a mobius strip: the social drama’s conflicts and characters fund the content of performances; and performances, in turn, color and inflect the social drama.[3] At every turn in the indicative social drama that was the Clinton-Lewinsky affair, a running metasocial commentary and critique occurred on the Internet. Hundreds of web sites, with names like “Official Guide To Zippergate,” “Tasteless Clinton/Monica Lewinsky Jokes,” “Starr Report—Just the Erotica,” and isleptwiththepresident.com, held thousands upon thousands of jokes, parodies, one-liners, poems, book titles, graphics, and song lyrics.[4]

While Turner couldn’t have predicted the rise of the Internet as a technology conducive to cultural performance, he certainly forecast its critical potential and the techniques it utilizes: “Genres of cultural performance are not simple mirrors but magical mirrors of social reality: they exaggerate, invert, re-form, magnify, minimize, dis-color, re-color, even deliberately falsify, chronicled events” (Turner 42). My first encounter with this magical mirror began on a tiny web site entitled, “In His Own Words.” “Impeach me!,” photo-shopped as a sign on Bill Clinton’s back, was the first image posted on the site.[5]

My first encounter with this magical mirror began on a tiny web site entitled, “In His Own Words.” “Impeach me!,” photo-shopped as a sign on Bill Clinton’s back, was the first image posted on the site.[5]

The now infamous encounter captured by CNN on video was typical (as we soon learned) of Lewinsky’s efforts to put herself in Clinton’s sight line. This image stood for the entirety of their two-year affair—at once clandestine and very public, at once cloyingly sweet and unashamedly licentious. This “photo-shopped” version, one of only four other manipulated photos on the site, is a stroke of genius. Casting Clinton as the butt of a school-boy joke speaks to a very sophisticated critical apprehension of the social power attendant to hegemonic masculinity, its institutional performances by men who enact it, and the cracks in the façade opened wide by social critique.

This essay explores just a fraction of the verbal and visual jokes posted on the Internet, from 1998 through 2003, to argue that the portraits of the President and his women are cultural investments in and protections of hegemonic masculinity. These texts work very hard to shore up hegemonic masculinity and to rescue heteronormativity. This cultural production is accomplished through the women of the social drama, especially Monica Lewinsky and Hillary Rodham Clinton. The lessons of Clinton-Lewinsky saga, some seven years after the drama’s resolution, speak to the perpetuation of gendered binaries and hierarchies in the service of phallocentric orders.

Cultural Performances on the Internet |

|

While political scientists and analysts have spent innumerable hours trying to account for Clinton’s ability to survive, even thrive, during the two-year saga, Americans on the Internet, with their Java Photo Lab software and musical wavs, brought acute critical skills and breathtaking creativity to the medium with their own accounts of Clinton’s survival.[6] At the same time, any analysis of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair as magically mirrored on the Internet must begin with several caveats. First, the vast number of texts available makes any claims to a single, or overriding, political or social meaning impossible. For each text that lovingly pokes fun at Clinton, there is an equal and opposite text that pours vitriolic. For every witty turn of phrase, there is a tired, recycled cheating-husband joke. For every clever doctoring of a photo, there is poor cut and paste job using a still photograph from hard-core pornography. To borrow a phrase from Yeats, “the center will not hold” given the immensity of created texts and political agendas available on the web. If there is a center, however, it is that all cultural performances are “flexible and nuanced instruments capable of carrying and communicating many messages at once, even of subverting on one level what it appears to be ‘saying’ on another” (Turner 24). Second, attribution in most cases is next to impossible.[7] While each text featured here was created by someone, the medium loosens authorial ties, sending these performances into cyberspace without the traditional legal protection developed for and afforded to print-based texts. Closer to oral folklore than printed literature, performance and dispersal on the Internet is collective. To use a market-based analogy, we each purchase a share in these texts when we retrieve them, save them on “favorites,” print them and post them on our office bulletin boards, forward them to friends, and participate in both their emergence as performances and livelihood as cultural artifacts. Like oral texts, the critiques of Clinton available on the Internet confuse our notions of textual “permanence.” At once readily available to those of us on the privileged side of the digital divide, they are also marked by planned obsolescence. When a web page is “No Longer Available,” it is really gone. To locate these texts in their historical and authorial specificity, part of any postmodern critique that rejects ahistorical, atemporal, universal narratives, is difficult if not impossible. Third, even if “no longer available,” the Internet represents an incredible cultural storehouse of folk material. Political jokes, especially those that feature sexual taboos like oral sex, have long circulated orally; their taboo topics flourishing precisely because traditional media outlets censored both language and acts (Oring). Most of these jokes “fall into oblivion,” and Alan Dundes claims that this is “another reason for recording them in print” in academic journals and books (47). Dundes analyzes a number of Gary Hart jokes, which circulated orally after Miami Herald reporters discovered him with Donna Rice on board a boat named Monkey Business, in 1987. Dundes asks, “Who knows how many ephemeral and brief political joke cycles in centuries past came and went without anyone thinking to record them for posterity” (48). Monica and Bill web sites are this record. As an incredible storehouse of oral and graphic texts, available for criticism and interpretation, at once a record yet unmoored from specific author, locale, and historical moment, these texts are thoroughly steeped in cultural and political structures. As such, these texts are exemplary of culture at play.

|

Playing With Hegemonic Masculinity |

| The intersection of play and performance is a rich site for textual analysis, and Turner speaks, again prophetically when applied to the Internet, to play’s forms and functions: Here early theories that play arises from excess energy have renewed relevance. Part of that surplus fabricates ludic critiques of presentness, of the status quo, undermining it by parody, satire, irony, slapstick; part of it subverts past legitimacies and structures; part of it is mortgaged to the future in the form of a store of possible cultural and social structures, ranging from the bizarre and ludicrous to the utopian and idealistic . . . (Turner 170) In Eric Fassin’s analysis of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair, he asks, “How can we even evoke the parallel with the Dreyfus Affair without falling into parody, and how can one seriously talk of ‘Monica Dreyfus’?” (153). With these questions, he discounts the seriousness of play and its possibilities for critique.[8] Ludic critiques of the present, subversion of past legitimacies, and a storehouse of possible future cultural and social structures are the tripartite organizing principles of the Clinton-Lewinsky Internet texts. At the center of this chronological triptych is masculinity. Masculinity names and produces a set of power relations and social expectations, performed with varying degrees of success by individuals. A prescriptive set of behaviors is always difficult to create, especially given the ways that subject positions—race, ethnicity, age, sexuality, physical ability—are determinants of and determined by economic, social, political, historical, and geographic factors. Still, brave theorists try to name masculinity in ways that help delineate the powers and oppressions produced there. James Doyle, in an early work, offered five themes (or hortatory “thou shalls”) of masculinity in the West: Be successful, Be Independent, Be Aggressive, Don’t Be Feminine, and Be Sexual. For R. W. Connell, masculinities—hegemonic, complicit, subordinate, and marginalized—are interrelated and contingent upon each other. In a semiotic approach, masculinity is always set in opposition to femininity as the “unmarked term, the place of symbolic authority” (Connell 70). Hegemonic masculinity is established “only if there is some correspondence between cultural ideal and institutional power, collective if not individual. So the top levels of business, the military and government provide a fairly convincing corporate display of masculinity” (Connell 76). A few men succeed in this performance of masculinity: successful, wealthy, powerful--politically, socially, and sexually. These heterosexual, white men are both emulated and envied by other, “lesser” masculine subject positions. It is no great leap of faith to cast the President of the United States as both symbol and embodiment of hegemonic masculinity in the West.[9] The texts I analyze here take Clinton as symbol and embodiment of hegemonic masculinity very seriously, amidst the high hilarity that centers these political and social critiques. I argue that individually and collectively the jokes have two primary functions: to shore up hegemonic masculinity and to remember heteronormative sex acts. Both of these functions are accomplished through the women of the social drama. |

Shoring Up Hegemonic Masculinity: Exaggeration, Mobilization, and Excuses |

Many of the texts on the Internet work very hard to shore up hegemonic masculinity, endorsing and envying the privileges held by Bill Clinton, even while lampooning him for, perhaps, performing masculinity too well. Clinton’s masculinity is secured in these texts in three ways: 1) through exaggerating numbers of sexual partners; 2) by mobilizing other, complicit masculinities in his performance; and 3) by excusing his actions with biological or Freudian motives. Like the indicative social drama, these cultural performances critique individual rule breaking, but never question the phallocentric center that is masculine sexual pleasure. In the Starr Report, Lewinsky’s testimony relates that: “Earlier in his marriage, he told her, he had had hundreds of affairs; but since turning 40, he had made a concerted effort to be faithful.” Jokes on the Internet constantly reference these numbers, recalling tall tales and hyperbole of traditional folklore:

• How is Bill Clinton different from the Titanic? Only 200 women went down on the Titanic.

• How did Bill manage to create such a large gender gap in the '96 election? One woman at a time. • Bumper sticker seen on Arkansas car: "Honk, if you haven't had sex with Bill Clinton." • How many women does it take to satisfy Bill Clinton's sexual appetite? It takes a village. • In a survey of over 500 women, when asked if they would make love to the president, 83 percent of them responded, "Never again."[10] Clinton’s famous disclaimer, “I did not have sexual relations with that woman, Ms. Lewinsky,” is performed anew on the Internet: “I didn’t have sexual relations with that woman . . . or that woman . . . or that woman . . . or that one over there either.” Exaggerating the numbers is matched by exaggerating Clinton’s sexual prowess and capacity.

• What do Bill Clinton's dick and a Chevy truck have in common? They're both like a rock.

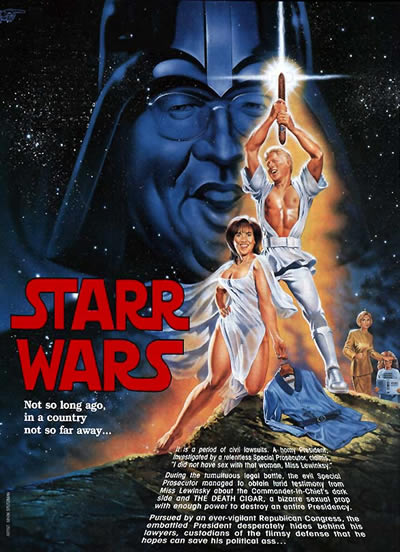

• A new Clinton bumper sticker: "Vote for the Man Who's Always on Top." • You can say what you want about Bill, but you have to admit he’s a very upright man. • Hillary Clinton arrives at St. Peter’s Gate. On the wall are giant clocks. She asks why there are clocks in eternity. She is told the clocks measure adultery and that every time someone commits adultery the clocks tick forward just a little. She asks to see her husband’s clock. St. Peter says, “Because your husband was President of the United States he has the grandest clock of all, but you can’t see it because God likes to keep it in his room and use it as a fan.” These jokes, circulating in and through the Internet, the late night talk shows, talk radio, and word of mouth, bolster and endorse hegemonic masculinity’s privileged access to sexual relations with women. While promiscuity is certainly implied, it is not judged as deviant or immoral—the usual condemnations when gay men, lesbians, and heterosexual women have multiple sex partners and engage in a variety of sex acts. Indeed, sexual prowess, masculine privilege, and antagonism is fun. One particularly entertaining rendition of the indicative social drama grafts the story line onto another iconic cultural performance in which enemies and allies are already scripted: George Lucas’ Star Wars. This text captures the constructedness of masculinity—as idealized body, spirit, and deeds thoroughly undone by its faulty performance. Neither Bill Clinton’s nor Mark Hamill’s body is accurately rendered in this text, but instead the hero is drawn with the white muscles of other iconic filmic heroes, Tarzan, Hercules, and Rambo (Dyer). His heroic, idealized body, however, is brought down by the spirit’s inability to control another sexual icon/weapon: “THE DEATH CIGAR, a bizarre sexual prop with enough power to destroy an entire Presidency.” Clinton is also thoroughly uncourageous in his role as hero. The text reads: “the embattled President desperately hides behind his lawyers, custodians of the flimsy defense that he hopes can save his political ass.” Hegemonic masculinity is also secured by mobilizing other, complicit masculinities—both friends and foes. “Lord of the Flings” is amazing testimony to the staying power of the sexual social drama: December 19, 2001 marked the theatrical release of The Fellowship of the Ring; the last day of the Impeachment Trial was February 9, 1999. Indeed, masculinity is always performed in relation to other men; its accomplishment measured and evaluated by betters and lessers. In his analysis of the Kama Sutra as a thoroughly heterosexual text, Gargi Bhattacharyya writes,

Although the focus is upon pleasure, not reproduction, the logic of heterosexuality bubbles up through every crevice of the text. This is the heterosexuality that assumes male sexual pleasure as its center. . . This central role is determined by social power, as always—so other less powerful men can appear as side characters, another option among the sexual servicers of [male] citizens. (18)

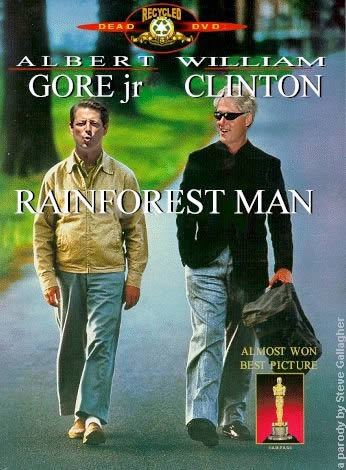

All quest dramas are masculine, whether Star Wars or Lord of the Rings, the gender roles firmly entrenched in embodiments and enactments of heroism.[11] The concomitant sexual roles, “other less powerful men,” staff, consultants, and friends also “service” the President with spin jobs. With hegemonic masculinity at its center, no man in the social drama is left untouched by commentary on the Internet. Al Gore, already institutionally one down to Clinton, is most often portrayed as asexual and decidedly boring. The occasional pairing of Gore and sex points to Clinton.

• What did Al Gore say when he heard of Clinton’s troubles? I’m only one orgasm away from the Presidency!

• Al and Bill were discussing pre-marital sex. Al asked Bill, “I never slept with my wife before we were married, did you?” Bill replied, “I’m not sure, what was Tipper’s maiden name?” The most interesting graphic rendition of Gore’s one-down status is “Rainforest Man.” The brushstrokes that paint hegemonic masculinity as potency, prowess, countless partners, and on top of both women and other men are a storehouse of cultural expectations for the masculine. At the same time, these same portraits must also deal with the fact that Clinton--stupidly, clumsily, and foolishly--got caught “thinking with his cock." These jokes shore up hegemonic masculinity with excuses most often centered in a biological determinism or a Freudian read of unresolved conflicts. A host of cock-for-brains- jokes are grafted onto the President: “Why is there a hole in the end of Bill Clinton’s penis? So he can think with an open mind.” Most jokes rallied around the biological imperative for masculinity, doing what comes “naturally” with willing women. "The White House scandal wasn't really Bill's fault, it was just something he got sucked into." Or, “I’m with stupid.”

To have the Phallus is to be impotent, and to live under the horrifying secret of one’s own inadequacy to the ideal. Under patriarchy, men had the double standard to hide behind; for women in post-Oedipal society, the consequence has been more of a double bind. And nowhere is this double bind more effectively embodied than in the handy opposition between Hillary Clinton—the middle-aged female professional as icy superego—and Monica Lewinsky—the sassy young professional of leisure. If Hillary is all work, then Monica is all play, the ‘liberated’ female libido of the post-Oedipal order. (557)

The Freudian read is also evident in Richard Schechner’s analysis: he casts the characters in the social drama in Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannus, with Clinton as Oedipus and Hillary as Jocasta. Even Linda Tripp becomes a “shepherd and messenger,” “small timers in ancient Thebes” who “nail the case against Oedipus” ("Oedipus Clintonius," 5). The Oedipal connection is not lost on the folk of the Internet, however. In clear testimony to their critical power, another Freudian read of the phallic stage of psychosocial development is brilliantly played out in a web page entitled “Oedipus Prez.” The text begins:

We’ve seen a seemingly endless parade of women get in front of the camera and claim they were sexually harassed by—or had sex with—Bill Clinton. Is it all about power or is he simply oversexed? Well folks, Tammy and her sandbox sleuths have proposed a new theory. It’s an Oedipal thing. They all look like his mother! We dug up photos of the women in question at the time of their “alleged” involvement with Clinton. Examine the following and draw your own conclusion.

The head-shots begin with Virginia Kelley (captioned “Dear old mom when she was young and vivacious. Doesn’t she look eerily familiar??? Big dark hair, full lips”), move through Paula Corbin Jones, Monica Lewinsky, Gennifer Flowers, Kathleen Wiley, and end with Hillary Clinton (captioned “No wonder Hillary isn’t getting any action—she doesn’t look like mom!”) The critique of Clinton’s infantile, impulse control problems on the Internet doesn’t end, however, with his Oedipal (or her Post-Oedipal) leanings. The most common, and enduring, item in the Internet corpus is the Dr. Seuss’ version of Clinton’s grand jury testimony, casting both Kenneth Starr and Bill Clinton in Green Eggs and Ham.

I am Starr. Starr I are.

I’m a brilliant barri-star. I’m here to ask, as you’ll soon see, Did you grope Miss Lew-in-sky? Did you grope her in your house? Did you grope beneath her blouse? Did you grope her on a train? Did she blow you on your plane? I did not do that here or there! I did not do that in a chair! I did not do that anywhere! I went not near her giant hair! I broke some rules my Mama taught me. I tried to hide, but now you’ve caught me. I do implore, I do beseech, do not condemn, do not impeach. I might have got a little tail, but never, never did I inhale.[12] Casting the antagonists in Dr. Seuss’ fantastic worlds is social critique that serious apprehension of the social drama missed: the Starr-Clinton battle over high crimes and misdemeanors is turned into silly, whimsical rhyme more suitable for the nursery than the state house. The relentless accusations and constant denials mirror the Seuss text not only in form, but also capture the Starr Report’s description of sex acts: “grabbing, groping, poking, and licking that read like teenage foreplay” (Langman 524). Sallie Tisdale argues that American attitudes about sex are “adolescent; there is no other word for our restlessness and preachy finger-shaking” (14). The Clinton deposition as “done by Dr. Seuss” critiques this perpetual adolescence and the “preachy finger-shaking” performed by both Starr and Clinton. One metamessage in this text is that everyone needs to grow up. Masculinity in these texts is constructed via several routes: as a sexual achievement—measured in numbers of partners and in excessive prowess; as a gendered accomplishment—related to and enabled by other masculinities; and as a process of psychosocial development. Only within the third category does Clinton “fail” to evidence an ideal masculinity evidenced by controlled rationality. Victor Seidler writes:

As men we do not want to be thought of as "unreasonable" or "irrational", for this is to be thought of "as a woman". We learn to identify our masculinity with control as domination of our emotional lives. It is because we can control our emotions that we can know we are men. This is a difficult taboo to break, for it challenges quite central cultural notions. (16)

The convenient Freudian read (Clinton’s unresolved Oedipal conflicts or Lewinsky as ‘liberated’ female libido) marries with the biological imperative argument (he only did what comes “naturally”) to absolve Clinton of responsibility for his lack of control. This absolution reveals the constant fiction that is hegemonic masculinity and our cultural insistence that its privileges not be undermined. The social critique available in these texts never questions the privileges of white masculinity, but it does critique Clinton’s inability to perform its particulars. Real men, these texts maintain, don’t get caught with their pants down. |

Rescuing Heteronormativity |

Part and parcel of hegemonic masculinity is heterosexuality. Gayle Rubin’s twenty year-old sex hierarchy delineates the “charmed circle” of “good, normal, natural, blessed sexuality” as “heterosexual, married, monogamous, procreative, non-commercial, in pairs, in a relationship, same generation, in private, no pornography, bodies only, and vanilla.” The “outer limits” of “bad, abnormal, unnatural, damned sexuality” violates each element: homosexual, unmarried, promiscuous, non-procreative, commercial, alone or in groups, casual, cross-generational, in public, pornography, with manufactured objects, sadomasochistic” (Rubin 281). Just what were the Presidential sex acts with Lewinsky over two years and ten encounters? According to the Starr Report, here are the Clinton/Lewinsky sex acts:

The President and Ms. Lewinsky had ten sexual encounters . . . On nine occasions, Ms. Lewinsky performed oral sex on the President. On nine occasions, the President touched and kissed Ms. Lewinsky’s breasts. On four occasions, the President also touched her genitalia. On one occasion, the President inserted a cigar into her vagina to stimulate her. The President and Ms. Lewinsky also had phone sex on at least fifteen occasions.

Clearly, Rubin’s “charmed circle” needs an upgrade to account for the infractions that centered the social drama: the problematical issue of sexual consent at work between superiors and subordinates; the moving target of “vanilla” sex which now includes oral sex as commonplace among certain age and racial groups; phone sex as a vexed public/private issue with masturbation at its center [13]; and the overriding question, “What constitutes sexual relations?” Indeed, the jokes on the Internet work very, very hard to remember heteronormative sex acts, specifically vaginal penetration by a penis and Masters and Johnson’s “human sexual response cycle” (excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution).

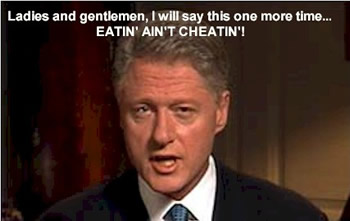

• What was Clinton’s excuse this time? I didn’t impale.

• If you smoke dope but don’t inhale, it doesn’t count as drug abuse. If you get a blow job but she doesn’t come, it doesn’t count as sex. • It isn’t sex unless you smoke a cigarette. • If the sex is just oral, it is not really immoral. • If she is not spread eagle, then it is not illegal. • Bill was asked, “Do you consider oral sex adultery?” Bill replied, “Not unless someone talks about it.” These jokes and turns on Johnny Cochran’s famous phrase (“If the glove doesn’t fit, you must acquit”) are telling for their construction of heterosex. Penetration, orgasm, even the cigarette afterwards, point to the processual stages and acts of heteronormativity. Nor does heterosexuality exist in a vacuum: religion (immoral) and law (illegal) are two systems called upon to legitimate or condemn sexual relations and sex acts. Adultery is a transcendent term for both religion and law; adultery requires someone to “talk about it” to produce its effects. My favorite graphic is a new caption for Clinton’s infamous January 26, 1998 denial of sexual relations with “that woman, Ms. Lewinsky,” captioned Eating Ain’t Cheating. One read of the Presidential sex acts, however, finds them overwhelmingly within the “charmed circle” of heternormativity. The new questions, however, are very much about power within sexual relations and the power to “name” sex in ways that perpetuate privileged sexual positions. Indeed, the texts on the Internet paint hegemonic masculinity and its sexuality through sex acts that always fulfill heternormative assumptions, and the jokes conveniently forget elements of these acts that contradict these assumptions. The best way to remember heteronormative sex acts is to remember Monica Lewinsky. The thousands of jokes paint Monica Lewinsky in three complementary ways: as a whore, as an accomplished fellatrix, and as worthy of congratulation for her sexual exuberance. Many of the jokes on the Internet graft her name onto tired “whore” jokes, the too frequent accusatory label applied to sexually active women.

• So Bill stopped playing his saxophone; now he plays the whoremonica.

• What’s Kenneth Starr’s opinion of his chances of prosecuting the President? It’s an open and slut case. • Johnny Cochran’s two closing arguments for the impeachment trial: Lewinsky’s a whore, and Bill’s better than Gore; and Bill is not sleazy, Lewinsky’s just easy. • Nixon had Ho Chi Minh; Clinton had a ho. • Ad in the Washington Post: Hor-Monica For Sale, Cheap, Slightly Used, Still Blows. The censure of Lewinsky, however, seems to end with that simple label—with no additional attention paid to heaping further moral judgments upon her for her sexual exuberance.[15] If there is one condemnation of Lewinsky, then it’s for her “kiss and tell-all” admissions. This item delineates just two questions from numerous examples of the “White House Intern Job Application.”

Do you or any of your friends own a tape recorder?

No ___ Grand Jury Alert ___ Do you keep a diary? No ___ Yes ___ If yes, do you lie to it? Instead, perhaps in keeping with the most popular service provided by prostitutes to their male clients, hundreds of the jokes deal with oral sex.[16] Several sites kept tabs on the most popular Clinton joke. For several months in early 1998 it was, “Why can’t they prosecute Bill Clinton? Monica swallowed the evidence.” Monica's autobiography titles include: All the President's Semen, One Blew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, and How to Suckseed in the Oval Office Without Really Trying. The jokes celebrate the act itself and congratulate Monica for her talents.

• What do you get when you cross Monica Lewinsky and Timothy McVey? A bomb ass blow job!

• There’s a rumor circulating that Monica has been arrested. The charge? Receiving swollen goods. • Paula Jones asked her advisors, “Why is Monica more popular than me?” To which they responded, “She was busier than you.” • What was Monica’s favorite childhood game? Swallow the Leader. • What was Monica’s official title? Head Intern. • Secret Service code name for Monica: The Hoover. • Bill’s just proven there’s one job he wants more than being President. • When asked about Monica’s best feature the President replied, “She’s got the whitest teeth I’ve ever come across!” Given the frequency of fellatio in their encounters (nine times out of 10), perhaps the abundance of blow job jokes is an accurate reflection of the indicative social drama; what the jokes conveniently forget is that the President climaxed only in the last two encounters, according to the Starr Report.[17] If the President only came twice, then the jokes fix that: “In Kennedy’s time we had Camelot. In Clinton’s time we have CAME-A-LOT.” All these jokes remember and feature masculinity’s stakes and pleasures in the heteronormative performances that perpetuate it.[18] Many of these blow job jokes are recycled from a cultural storehouse of “blue” material, dirty jokes, and double entendres. If there’s anything new in the jokes, then it is attention paid to Monica’s playful invitation to incorporate a cigar in their sex acts. In a refreshing deflection from Monica as whore, the folk on the Internet take up Monica’s invitation with a vengeance, incorporating the cigar into a variety of cultural genres, famous phrases, and formulas for jokes: from the t-shirt, “My grandparents visited the White House and all they got me was this slimy cigar,” the reframed Johnny Cochran couplet, “If the cigar fits, you can’t acquit,” the Republicans are searching for the “smoking cigar,” Clinton’s cigar “has gone where no cigar has gone before,” when asked to compare Paula Jones to Monica Lewinsky, Bill Clinton said, “Close, but no cigar,” to song lyrics sung to the tune of the Beatles’ song Eleanor Rigby.

Monica Lewinsky picks up cigars in the Oval Office where the president has been

Lives in a dream Waits under the desk, wearing the stained dress that she keeps on a hanger by the door Who is it for? All the lovely bimbos Where do they all come from? All the lovely bimbos Where can I get me some?

As hard as the Starr Report worked to present Lewinsky as a victim of an oversexed, underscrupled man, I could find only one item that presented Lewinsky as the injured party in the affair; she is victim of the cigar, however, not the President.[19] The graphic line-up of cigar perpetrators has two captions: “Ms. Lewinsky, can you point out the suspect that raped you?” and “Ken Starr: Ok, I know one of you was in the Oval Office. We’ll stay here all night if that’s what it takes.” The cultural fascination with this sexual “prop” is a telling moment for hegemonic masculinity. The abundant humor available in the cigar deflects attention from a tremendous ellipse in the cultural storehouse of material. That is, the jokes conveniently forget images of the masturbating President. I could find only two references, out of thousands of jokes and images, to Lewinsky’s testimony that she saw “the president masturbate in the bathroom near the sink,” and observed “the President ‘manually stimulating’ himself in Ms. Hernreich’s office.”

• First we had Whitewatergate, then Travelgate, then Filegate. Now we have Masturgate.

• So what did we get for $40,000,000? More comic material than Gerald Ford, Jimmy Carter and Dan Quayle put together.—We’ve gone from “lusting in my heart” to “beating off in a sink.” This missing merchandise in the subjunctive storehouse testifies to the “powerful nineteenth-century stigma on masturbation [that] lingers in less potent, modified forms, such as the idea that masturbation is an inferior substitute for partnered encounters” (Rubin 279). While the president’s penis is exaggerated and venerated in the jokes, the president’s hand on that penis is too potent, too painful, and too disruptive an image to lampoon for it strikes at the heart of the faultline in constructions of the masculine. That is, Clinton is not responsible for his urges or his acts, as long as Lewinsky is involved. Mary Holmes hits the nail on the head when she writes, “In the discourses surrounding hegemonic masculinity sexual responsibility is routinely displaced onto women so men can supposedly function as rational politicians. . . . It is the sexualized ‘wild ladies’ who are at fault” (311). Clinton is thoroughly masculine as long as Lewinsky is servicing and shoring up his performance of hegemonic masculinity and heterosexuality. The moment she moves out of the sexual picture, however, we are left with Clinton—alone with his erect penis. Sallie Tisdale writes of masturbation,

There is a wonderful and awful moment for each of us when we practice masturbation as a conscious act—when we know what to do and why we want to do it, and make plans. Though I’d been chastised for my unconscious masturbation when quite young, it was not a sin until I planned and carried it out consciously. And ever afterward, masturbation has been accompanied by a strange, potent mix of emotions: desire, guilt, excitement, shame, fantasy, and, especially, the fear of getting caught. (21)

While “fear of getting caught” is implicit in Rubin’s “in private/in public” continuum, presidential sex acts are not of the public parks or bathrooms variety. Instead, U.S. presidents live in “total institutions,” the term Erving Goffman (Asylums) applied to prisons, nursing homes, and residential care facilities—“whole life” settings in which individuals, unable to leave, are under constant observation. “Don’t be overwhelmed by all this,” Clinton supposedly told Paul Begala during a private White House tour. “The White House is the crown jewel in the American penal system.” The image of the masturbating President—in a bathroom or on the telephone during phone sex—is not fodder for parody for it thoroughly undermines the power produced by the material and discursive institution that is the Presidency and its attendant social and political power. Pat Califia’s analysis of sadomasochism is relevant here:

Our political system cannot digest the concept of power unconnected to privilege. S/M recognizes the erotic underpinnings of our system and seeks to reclaim them. There’s an enormous hard-on beneath the priest’s robe, the cop’s uniform, the president’s business suit, the soldier’s khakis. But that phallus is powerful only as long as it is concealed, elevated to the level of a symbol, never exposed or used in literal fucking. A cop with his hard-on sticking out can be punished, rejected, blown, or you can sit on it, but he is no longer a demigod. In an S/M context, the uniforms and roles and dialogue become a parody of authority, a challenge to it, a recognition of its secret sexual nature. (Public Sex 166)

While the folk of the Internet are more than willing to parody and to challenge Bill Clinton’s performance of hegemonic masculinity, the absence of masturbation jokes reveals a terrible duplicity about “self” gratification. While S&M unlinks power and privilege, solitary masturbation reveals the sociality of heteronormativity; it takes two to produce heteronormative identities, discourses, and institutions of gender and sexuality. Masturbation’s ties to adolescence, furtive secrecy, lingering “shame,” and singularity, are exacerbated in Clinton’s White House “total institution.” His demigod status—as the most powerful leader in the Western world—is perpetuated by Lewinsky’s physical presence and thoroughly undone by his own hand. These cultural performances rescue and remember heteronormative sex acts—as penetrative, as processual, and as centered on male orgasm as completion—and return them to the indicative social drama that denied them. The jokes revel in blow job jokes, forgetting that the President came only twice; the jokes revel in the cigar, forgetting that the President never “penetrated” Lewinsky with his penis; the jokes revel in great heterosex, forgetting that the President masturbated without her. Shoring up Clinton’s masculinity depends on heteronormativity. And Monica is only one of the “President’s women” who accomplishes those feats. |

Accomplishing Masculinity through First Lady Complementarity

When the jokes turn to the feminine, the women of the social drama are cast as either willing accomplices to hegemonic masculine sexuality or as lesbians, ice-queens, or “bitches” immune to Clinton’s sexual power. None of these constructions of femininity threaten Clinton’s iconic status. If Lewinsky is laughingly, but affectionately, a “good gal,” then Hillary Rodam Clinton is not. An item on still another “White House Intern Job Application” brilliantly summarizes all the approaches to Hillary in the corpus of Internet jokes:

Hillary Clinton is a(n):

a) model wife and mother.

b) icon of late-20th-century femininity.

c) obstacle.

d) inappropriate companion for the leader of the free world.If answer “c” is putatively Monica’s choice, the other three alternatives are vividly portrayed on the Internet, capturing both contemporary understanding and confusion regarding gender roles and sexuality embodied in Hillary.

“Model wife and mother” might seem an odd label to apply to Hillary, but many of the texts paint her in just this role: vigilant in protecting her child and her family; understanding and forgiving of Bill’s sexual dalliances; the unwitting, blameless victim of circumstances. Perhaps the best example of this is her portrait in Starr Wars.

In the far background of the picture, shielding Chelsea’s vision[20], she performs the “model role” of wife and mother.[21] Unassuming, unassertive, backdrop to the real action—sexual and political— nevertheless she is a necessary character in the drama.

This laundry list of characteristics of model wife and mother, vigiliant, protective, and unwitting victim, is also a laundry list for the role of First Lady. For Germaine Greer, the primary function of the First Lady is to “reassure us of the head of state’s active heterosexuality” (22); her second function is to be a “virtuoso housekeeper.” Anastasia Sims adds motherhood to the list: "being a good first lady meant hailing, modeling, and promoting publicly the civic values that good mothers historically instilled" (576-77). The First Family, and the “joint image-making” that creates it (Troy) takes the social imaginary family to its zenith. Darlaine Gardetto writes:

The Family (capitalization intended) understood as Mom, Dad, and the kids—with Dad as primary if not sole breadwinner and Mom serving as an emotional support for her husband and as emotional core of the family—is the social imaginary family. . . This way of thinking about familial relations, I argue, contributes to women’s subordination by supporting the idea that women’s proper place is in the home. The social imaginary family is linked to the first lady symbol. (226)“School Children”

is a brilliant commentary on this conception of family, with its prominent father and supportive mother, surrounded by the kids. Captioned on the site as “What the President is teaching our children,” the public debate over the President’s morals and “character” is transformed into images that make no mistake about the lessons learned. The children’s expressions run the gamut—from obliviousness, nonchalance, eagerness, to shock—but Hillary’s expression is thoroughly supportive. Her neat, buttoned-up, “model First Lady” attire contrasts vividly with the nude women, the “wild ladies,” in the (President’s story) book.

Texts on the Internet also speak indirectly to the “model” wife’s ability to look the other way and to suffer the indignities of infidelities with a smile on her face. “An Invitation to the White House”

does just this. This is a “photo-shopped” cover of Hillary Rodham Clinton’s book, An Invitation to the White House: At Home with History, published in 2000 by Simon and Schuster to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the White House. The book is thoroughly invested in constructing Hillary as first “Homemaker,” with sections entitled “Making This House a Home,” “Christmas at the White House,” and ninety pages of recipes from the White House kitchen. The front flap of the book can be read satirically in light of the doctored version: “This is a White House you won’t see on any public tour: As historian Carl Anthony writes in his introduction, ‘This book makes the rooms come alive—one can almost taste the food and hear the music’” (front flap). The Internet text invites the viewer to add, “and watch the soap opera!”

Hillary’s posture features the multiple roles of First Lady: hostess, tour guide, homemaker, perhaps even a reference to her role as holder of the “white glove pulpit”—the power afforded to First Ladies to advocate social programs and agendas.[22] So much in this text complicates these public functions with the private affairs that centered the social drama. Here, the white glove is dubiously singular—for perhaps Hillary is making sure she leaves no fingerprints on the “Billing Records” from the Travelgate affair? The portrait on the wall (in soft focus on the real book cover) is now Karl Marx.[23] Bill holds a teddy bear, a gift from Monica. Most importantly, Hillary seems oblivious to the shenanigans under the desk: the “model wife and mother” is the last to know.

Many of the jokes that feature Hillary as model wife are, once again, borrowed from the cultural storehouse of philandering husband jokes, slipping in the names—Bill and Hillary—in place of generic husband and wife.

• What’s the worst thing Bill ever heard during sex? “Honey, I’m home!”

• What does Bill say to Hillary before a romantic interlude? “Honey, I’ll be home in 20 minutes.”

• Why did Bill Clinton cross the road? To get back to the White House before Hillary did.[24]A riff on these husband jokes also points to the lack of desire, lack of sexual activity, and lack of sexual experimentation within a long-term married relationship.[25]

• What position does Hillary play on Clinton’s sex team? Left out.

• Who is the only woman in the White House not having sex with Bill? Hillary.

• Bill + Monica=Slick Willy. Bill + Hillary=Slack Willy

• When asked what was the difference between a night of bowling and a night with Hillary the president replied, “If I had to I could eat the bowling ball.”

• The Right Wing Cabal said they're no great fan of Hillary, but they don't think she sucks.The limerick is a poetic form that flowered during the Clinton-Lewinsky affair, and its typically bawdy content grafted neatly onto the sexual saga. While most of the poems feature Lewinsky, this limerick is unusual for its focus on Hillary.[26]

There once was a prez named Bill,

whose interns all know the drill.

He’d say, “Get on your knees,

and service me, please!

‘Cause I don’t think Hillary will.Hillary as “model wife” is neither an object of sexual desire nor a desiring subject. In the jokes, Hillary’s unwillingness to engage in oral sex is a vivid contrast to Monica’s exuberance, shoring up wifely sexual duties as decidedly boring, prudish, and vanilla. That Hillary “suffers in silence” as model wife is evidenced by jokes that name her as the object of derision, but never give her first-person voice.

The second choice in the multiple-choice question, “Hillary is a(n) icon of late-20th-century femininity,” is fascinating testimony to our cultural awareness of changing roles for women, the pressures brought to bear by shifting political, economic, and sexual tempers, and the centrality of Hillary as “icon” in the cultural landscape. Karrin Vasby Anderson neatly summarizes Hillary’s lighting rod capacities:

During her tenure as first lady, Clinton either was reviled or lauded for the challenges she posed to traditional femininity. She was seen as an icon of feminism, a threat to femininity (or masculinity), an embodiment of the complex roles facing modern women, an everyday baby-boomer struggling with marital problems and empty-nest syndrome. (109)The jokes on the Internet become a catch-all for these conflicts, capturing numerous double-binds: professional woman and homemaker; sexually desired and desiring; at once responsible for her husband’s behavior and unable to do anything about it. A number of jokes pun on “first” in First Lady, as well as incorporating other “news” items:

• Why does Hillary want to have sex with Bill every day at 5am? She wants to make sure that she is the first lady.

• How does Hillary feel? She may be the FIRST LADY, but she won’t be the LAST.

• What’s the name of Hillary Clinton’s new White House intern? Lorena Bobbit.

• What does Bill tell Hillary after sex? Nothing, she hears about it on the evening news.These jokes seem particularly poignant renditions of many married women’s lives: “A First Lady symbolizes the collectivities of wives who are caught between the symbolic spaces of the political and domestic spheres, and who are under attack for having access to power” (Edwards and Chen 386).

The most interesting approach to Hillary in the multiple-choice application is “inappropriate companion for the leader of the free world,” for it opens the door to a number of parodies and pictures of Hillary, as well as highlighting the complementarity of gender roles. If Bill is the paradigmatic masculine “leader,” then Hillary must be the paradigmatic feminine “follower.” The texts on the Internet thoroughly blast her for her unwillingness to play this complementary role: “Why does Bill Clinton cheat on Hillary? He wants to be on top.” Perhaps playing on Newt Gingrich’s mother’s infamous interview, in which she characterized Hillary Clinton as “rhymes with rich,” the jokes freely use the real term.

• Why did Bill Clinton buy a MALE chocolate Lab for the First Dog? Because there was already one FIRST BITCH in the house.

• Have you heard the new meaning for the word B.I.T.C.H.? Bill’s In Trouble, Call Hillary.If the first joke pours venom with all capitals, then the second rallies around the power captured in the word.

T

his “power,” however, takes a number of turns in some amazing graphics. In Lord of the Flings, Hillary is “The Witch Queen,” and an uncaptioned text takes a delightful S&M route to her power. Perhaps the most powerful critique of Hillary pastes her face onto a portrait of Hitler, captioned “the Fuhrer.”

Whether witch, dominatrix, or the most reviled man in contemporary history, Hillary clearly stands for contemporary fears and confusion about feminine power—mythical, sexual, and political. Without the watchdogs of mainstream media, the Internet is a forum that takes those fears to the limit and is fearless in attributing sources:

In response to many inquiries from her devotees, Judith Martin (“Miss Manners”) has decreed that the preferred term whenever addressing or referring to first lady Hillary Clinton, is “madam.” Citing Teapot Dome, Watergate, Iran-Contra and Zippergate, she said, “It’s become clear to me that the President’s wife essentially is responsible for running a house of ill repute.”This “madam” joke nicely illustrates the tension all First Ladies have felt, caught in the public/private bind, especially in the age of celebrity. “How do you maintain your privacy while peddling your life story?” (Troy 379). Texts on the Internet exploit this tension and revel in speculation.

Indeed, the Internet gives loud voice to quiet rumors of Hillary’s possible love affair with Vince Foster and her “questionable” sexual orientation (Templin). In her analysis of editorial cartoons, Templin writes, “To actually portrait Hillary Clinton as a lesbian in a cartoon would be more daring than a mainstream newspaper could allow and presumably would be libelous” (25). Internet jokes, however, fear no such repercussions. Lesbian jokes on the Internet, however, have a decidedly homophobic flair, casting the lesbian as a “failed woman” or “wannabe man.”

• How did Bill and Hillary meet? They were both dating the same girl.

• Official “Vast Right-Wing Conspiracy” alert: We no longer support the theory that Hillary had an affair with Vince Foster. It’s Janet Reno. Pass the word.

• "You know two weeks after Bill Clinton leaves the White House, he'll be a free man."

"Yeah, so will Hillary."

• Why is Chelsea Clinton so ugly? Because Janet Reno is her dad.

• Hillary sleeps with as many women as Clinton and almost as many dead men.The “photoshopped” Spy Magazine cover caption, “Where that shady $100,000 came from and what it bought,” references Hillary’s $10,000 investment in cattle futures and its $100,000 return.

As the wind blows, reminiscent of Marilyn Monroe’s famous Seven Year Itch scene, the graphic reveals not only her tighty-whities, but her erect and moving penis. While Marilyn’s dress was white, Hillary’s is black, recalling witchery, the “dark” arts, and cultural condemnation of blackness (Dyer). Taking the cliché, “the real pants in the family” to its logical extreme, “Hillary’s Big Secret” not only portrays Hillary’s sexuality as threatening to Bill’s masculinity, but as thoroughly “unnatural,” appropriating the phallus and the power that adheres there. That she “bought” this penis, supposedly through a sex-change operation, recalls our cultural fear of transgendered individuals: “If we have a sense of ‘rightness’ about ourselves as men or women, gender outlaws scramble it. Gender dysphoria—even someone else’s—literally gets us by the short hairs, where we live, between our legs” (Califia, Sex Changes 2). Drawing Hillary as a “gender outlaw” cuts deep.

In the two years that comprised the indicative social drama, an odd thing happened: whenever Bill Clinton’s polls went down, Hillary’s went up, and vice versa (Pope). This is testimony perhaps to the zero-sum game that is masculine and feminine balance of power and our cultural inability to imagine gender and sexuality performed differently. Texts that paint Hillary as model wife, mother, an icon of contemporary femininity draw from a vast storehouse of cultural constructions of “woman,” drawn always in familial, political, social, and sexual relations to men. Hillary’s “inappropriateness” comes precisely at those moments when she is drawn without reference to men—as lesbian, dominatrix, or ice queen—or when she appropriates the “big secret” that is phallic power. These pleasures script her outside the phallocentric order that reduces all to the masculine. Hillary, in these multiple constructions of feminine and masculine on the Internet, is representative of larger cultural fears and desires—that of the feminine unanchored from its binary and hierarchical pairing with the masculine.

While the social drama scripted her most often as the wronged, yet supportive, wife, the cultural performances on the Internet found so much more to talk about. The future of Senator Hillary Rodam Clinton and her putative run for President remains part of the tripartite chronology of culture at play: parodying the present, subverting the past, and “mortgaged to the future in the form of a store of possible cultural and social structures, ranging from the bizarre and ludicrous to the utopian and idealistic” (Turner 170). Soon, I believe, we’ll start seeing cultural performances of a different kind, attendant to the possibility of a second President Clinton. Like the social drama and cultural performances that debated competing definitions of sexual relations, competing definitions of the masculinity and heterosexuality of the Presidency will surely center those conflicts. “Madame President” is already a double-entendre.

Of Phallocentrism, the President’s Penis, and Accomodations of Interest

A number of critics tried to account for the cultural lessons learned in the Clinton-Lewinsky saga. David Steinberg, psychologist and editor of a special edition of Sexuality and Culture dedicated to the affair, gave this advice to future politicians:

1) tell the truth if some non-standard aspect of your sexuality is exposed; 2) emphasize the consensual nature of any sexual encounters, however unconventional; 3) do not apologize for having a strong sex drive; and 4) trust the American people to understand and appreciate the reality that sexual energy does not always stay within the strict boundaries of social propriety, especially for the rich and famous. (10)Good advice for powerful white men. The same advice directed at Monica Lewinsky or Hillary Rodam Clinton, however, reveals the phallocentric boundaries and norms of heterosexuality with masculine sexual pleasure at its center. For Elizabeth Grosz,

Phallocentrism conflates the two (autonomous) sexes into a singular ‘universal’ model which, however, is congruent only with the masculine. Whenever the two sexes are represented in a single, so-called “human’ model, the female or feminine is always represented in male or masculine terms. Phallocentrism is the abstracting, universalizing and generalizing of masculine attributes so that women’s or femininity’s concrete specificity and potential for autonomous definition are covered over. (94)The impossibility of “human” sexual expression is made explicit in the social drama and in the cultural performances born out of it. At the center of both is the President’s penis. Lauren Langman claims, “The real audience [for the impeachment trial] was public opinion as each side tried to present competing images of Clinton that fell into two categories, the immoral Anti-Christ who personified evil, sin, and perfidy and the effective leader who had a problem keeping his zipper up” (525). Clinton’s penis centers both portraits of the man, whether it is characterized as “root” of all evil or as bothersome, if willful, appendage. Loren Glass explores the calculus that is patriarchy/phallus/penis in the Clinton-Lewinsky affair:

Patriarchy to a great degree depends upon concealing the anatomical penis behind the symbolic phallus. The penis—in the end a paltry thing—must be concealed if its fictional equation to the omnipotent phallus is to be sustained. All this attention to the President’s penis reveals that the patriarchy is in trouble, that traditional discourses of masculine symbolic authority are disintegrating. (After the Phallus 547)I would argue that this social drama and its attendant cultural performances did not evidence, or even foretell, the disintegration of patriarchy, but instead laid bare the social performance that is hegemonic masculinity and its reliance on complementary performances of femininity to produce it. The women in the drama—Hillary Rodam Clinton, Monica Lewinsky, Paula Jones, Betty Currie, even Chelsea Clinton (the list of women does tend to go on and on)—are always cast as both peripheral to that social power yet thoroughly implicated by their sexualized roles as wives, willing lovers, unwilling lovers, secretaries, and daughters.

More than sexual, racial, or economic “double standards” for women and for men, the social drama—as formal and informal institutions and procedures—works hard to veil the phallocentric order, even as the categories “man” and “wife” are hailed as social expectations. If Loren Glass misses the mark on the disintegration of the patriarchy, then Glass’ analysis of the continued vilification of women in the drama is thoroughly on the mark: “Clinton gladly concedes power to careerist ‘ice queens’ like Hillary Rodman, Janet Reno, and Madeleine Albright, while eagerly pursuing blowjobs from trashy young sluts like Monica Lewinsky and Paula Jones. As a model of the new sensitive male, he can have his cake and eat it, too” ("Publicizing," 30).

The performances on the Internet reveal the faultlines in cultural constructions of masculinity, even as they mask and protect the political and social power that produces masculine subject positions. “Gender equality” in a phallocentric system is an impossibility. Turner writes of the social drama, "Every social drama alters, in however minuscule a fashion, the structure of the relevant social field" (92). These alterations, Turner notes parenthetically, are not a “permanent ordering of social relations but merely a temporary mutual accommodation of interests” (92). The cultural performances on the Internet serve phallocentric orders: shoring up hegemonic masculinity, rescuing heteronormative sex acts, and painting femininity as complement to masculinity. Despite its walk through “taboo” notions—unveiling the President’s penis as “stupid” or Hillary’s penis as a “secret”—the cultural performances manifested on the Internet never truly threaten the cultural order. Instead, the cultural performances are fun-house mirrors of hegemonic masculinity that parody its faulty performance, but never its primacy. The phallus remains—laughed at, pointed to, commented on—but never unsecured from its rightful place.

In between the “wild” ladies and the First Lady were a number of women that both the social drama and cultural storehouse of jokes handled with relative care. Paula Jones, Kathleen Wiley, and Juanita Broadderick offered painful accounts of unwelcome advances, touching, and, in Broadderick’s case, rape. The antagonists in the indicative social drama, the “vast right wing conspiracy,” surely could use these women and their accusations to remove a sitting President? They failed, of course, revealing not only a level of cultural uneasiness about abusive masculine power and its potential, but a larger rift in hegemonic masculinity and the institutions that bolster it. Unable to make the terms “sexual predator” or “sociopath” stick in the media, in Arkansas federal court, or in the U.S. Senate, the antagonists in the social drama didn’t even try. Instead, they fell back on legal performatives divorced from sexual deviancy, aggression, or violence: perjury, subordnation of perjury, tampering with witnesses, obstruction of justice—all of these infractions concern words that produce their effects, instead of the sex acts performed. The deflected attention to “lying about sex” secured the President’s masculine prerogatives, white privilege, and active heterosexuality; any attention to a rape in a hotel room in Little Rock, Arkansas, some 25 years ago would cut much too close to the bone. The social drama’s resolution, its “temporary mutual accommodation of interests,” was satisfactory.

Cultural performances on the Internet left Juanita Broadderick alone. Her story was not fodder for jokes, images, or parody. And therein lies the seriousness of cultural play and our collective inability to reimagine power divorced from the interlocking mechanisms that produce sexual discourse, identities, and institutions. The metacommentary available on the Internet lovingly lampoons performances of hegemonic masculinity and remembers heteronormativity as accomplished through women, but the comic route is closed off when sexual power and privilege exceed its reach. The tragedy that was Broadderick’s tale, its unserviceability to the indicative social drama and its untouchability in cultural parody, is testimony to the difficulty of erecting a sexual politics that enables choice. For Foucault, this sexual ethics is not about “freedom of ‘sexual acts,’” but “freedom of sexual choice,” including liberty not to manifest choice at all (251). While the indicative and subjunctive moods of culture focus on the sexual acts and the discourse that valorizes or erases them, the ellipse in both constructions of sex is sexual choice. When a sexual ethics of choice pervades discourse, identities, institutions, and culture, the social dramas and attendant cultural performances will really be something to see.

Until then, social dramas and cultural performances continue. Indeed, the social drama of Bill Clinton might best be sandwiched between Gary Hart’s aborted bid for the Democratic Presidential nomination in 1984 and Arnold Schwartzenegger’s successful bid for the California governorship in 2004. The rules are changing. The relevant social field, however, is still very much about “mutual accommodation of interests,” and the women—groped, touched, and fondled—are again lost from our collective memory and from Internet web sites.

Notes

1. Wire service reports the next day detailed the “cyber-gridlock” as millions of Internet users logged on to read the Starr Report. Twelve million people, according to Ken Allard of Jupiter Communications, tried to access the Report on Friday, September 11. CNN Interactive, at 2:45pm, reported garnering 340,000 hits per minute on their site; American Online reported 62,000 downloads during the first hour of its posting (Kaplan and Huhn) and 600,00 users logged on simultaneously (Reid and Hume)

2. The saga of Bill Clinton’s sex life unfolded in fits and starts over two years, but the week of January 17, 1998, when the name Monica Lewinsky first hit the headlines, was unprecedented.A Washington research foundation, the Center for Media and Public Affairs, studied the amount of coverage during the first week of the scandal on the evening newscasts of the Big Three networks (ABC, CBS and NBC), and concluded that the Lewinsky story was the media’s “biggest feeding frenzy” ever. Between Jan. 21 and 27 [1998], the networks ran 124 stories on the scandal—more even than the 103 they ran during the week following the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, last August. To be sure, the public ate it up: audiences for the shows soared. (Phillips 23)

3. Perhaps the best example of this metaphor is Saturday Night Live’s Will Ferrell’s brilliant impersonations of Attorney General Janet Reno. When the real Reno crashed through the set, surprising Ferrell, suddenly the social drama (the “actual” events) met cultural performance (the “what if” of play) head on.

4. The names of web sites I found most useful in collecting texts for this analysis are listed below, but none of them are active sites on the web. In September of 1998, startingpage.monica had six screen pages of links to Monica/Bill websites. I counted over 500 active sites. I think we’ve lost—with the exception of this analysis and my shoddy attempts at archiving—an amazing compendium of cultural material such as “Tasteless Clinton/Monica Lewinsky Jokes: In the Beginning”; “Official Guide to Zippergate”; “A Bill Clinton Joke Compendium”; “Banjo Bob’s Joke Page”; and “Welcome to the Clinton Humor Page.” In 2005, the Monica Lewinsky webring had only 24 active sites. The Monica and Bill Page is typical of what was once available. The Bill Clinton Joke-of-the-Day Page contains archived years worth visiting.

5. This tiny website stayed active for only a month. I did find this same image here.

6. In the years since Monicagate, a number of scholars have tried to make sense of the political, social, and sexual lessons of the saga. Not surprisingly, distinctions between the personal and the political centered much of the discussion. Political scientists turned again to polling data to rethink notions of framing policy issues, media effects, and public perception (see Shah, Watts, Domke, and Fan; Lawrence and Bennett; Ahluwalia; and Miller). Most found the divide between private and public either firmly fixed or operating as backlash: “For most, the scandal was not about the rule of law or punishing a president who had lied under oath or obstructed justice; it was about a zealous special prosecutor who had spent many of their tax dollars doing the dirty work of the far right wing of the Republican party” (Miller 728). Media theorists and professionals were especially hard on themselves, asking “What went wrong?” in their journalistic accounts of private affairs (Hickey; Witcover; Steep; Gartner). Public interest and “sex sells” are still at the heart of political scandal news, but caution in utilizing Internet sources is the new watchword. For feminists, the public/private debates ought to have been a dream come true, but sophisticated critiques of the gendered constructions of public and private didn’t enable new ways through the impasse (see Elshtain; Deem; Holmes; Perloff).

7. And for purposes of academic citation, equally difficult. In this essay, I do not offer web addresses for specific items. Most of the same jokes appeared on dozens of sites; the images were spread, and repeated, across them. In 1998, I cut and pasted from dozens of web sites approximately 40 pages of jokes—single spaced, in 8-pitch font—to save space and paper. These hard copies and jpeg files saved on my hard drive were my “data” for analysis.

8. The Dreyfus Affair is one of two Western examples Turner often mentions as a well-known social drama. Turner’s second example, and much more familiar to Americans of my generation, is Watergate.

9. For analyses of the masculinity of the office and of individuals who have held it, see Edelmen, Jamieson, Tulis, and Medhurst.

10. I discovered several versions of this particular joke. The highest numbers were 1,200 women; 98% of them said “never again.”

11. See Mary Lefkowitz for a critique of Joseph Campbell’s monomythic cycle as a thoroughly masculine view of heroism and heroic action.

12. I found more than 10 different versions of this text across the Internet, and this is just a tiny sample of poems that continue for up to 30 stanzas, encompassing a wide spectrum of Clinton infractions. Only last year I stumbled across the “real” author’s account of what happened to his creation. Tom Tomorrow, a political cartoonist and creator of This Modern World, created a cartoon with Ken Starr as “a Grinch-y independent counsel grilling Bill Clinton in a Dr. Seuss-style rhyme.” The dialogue was cut from the cartoon, pasted into e-mail, and began its internet journey with new additions by “folk” and without Tomorrow’s name. Tomorrow said, "Thanks to the instantaneous nature of the Net, by the time people saw my cartoon they accused me of plagiarizing ... myself” (Stecker).

13. The Starr Report offers this definition: “Phone sex occurs when one or both parties masturbate while one or both parties talk in a sexually explicit manner on the phone” (Malti-Douglas 90).

14. The two-year long social drama of the Clinton-Lewinsky affair created an ever-shifting debate about the breach. Just what “rule” did he break? Clinton lied under oath. Clinton had an extramarital affair. Clinton obstructed justice. Clinton committed perjury. Clinton engaged in sexual relations with an employee. Clinton dishonored the office of the presidency. Pick a breach, any breach.

15. I do not mean to infer that the label alone is not harmful to women. Alex, a prostitute Sallie Tisdale interviewed, said: “It’s still true that the worse thing you can say to insult a woman is to call her a whore. ‘You fucking whore.’ It’s hard to grow up hearing that all your life and not internalize it. I know I have and it pisses me off, because this is a great line of work and it sucks that I have to carry around everybody else’s shame about it” (Tisdale 207).

16. Sallie Tisdale summarizes the amazing work of Martha Stein, a social worker who befriended prostitutes, and over four years, “claims to have watched 1,242 men with dozens of different women.” Tisdale relates some “surprising” findings of the sexual wants of these white, upper-class professional men: “Ten percent ‘exhibited homosexual impulses’; four percent cross-dressed during sex; forty-three percent wanted to perform cunnilingus. (A number of others said they were interested but too shy). One-third wanted anal stimulus or penetration. One-fourth had some kind of sexual dysfunction such as impotence. Almost every one wanted fellatio” (184-85).

17. “Initially, according to Ms. Lewinsky, the President would not let her perform oral sex to completion. In Ms. Lewinsky’s understanding, his refusal was related to ‘trust and not knowing me well enough.’ During their last two sexual encounters, both in 1997, he did ejaculate.”

18. Gary Hart jokes, according to Dundes, centered on cunnilingus and fellatio, perhaps because of the many puns available on the name Donna Rice: “Have you heard about the Gary Hart diet? You eat rice three times a day and lose everything” (Dundes 45).

19. Joan Didion’s observation on the Starr Report is fascinating. Didion characterizes the Starr-Report-Monica as the quintessential unreliable narrator. That is, “a classic literary device whereby the reader is made to realize that the situation, and indeed the narrator, are other than what the narrator says they are. It cannot have been the intention of the authors to present their witness as the victimizer and the president her hapless victim, and yet there it was, for all the world to read” (244).

20. Chelsea, interestingly enough, is not a common subject of joking, perhaps reflecting an understanding of what is “too much” in the realm of cultural parody. But one joke does stand out, not as condemnation of Chelsea, but as an indication of the difficult position her mother is in and her father’s role in creating those difficulties: Chelsea was getting ready to leave for college and Hillary used this opportunity to have a mother-daughter heart-to-heart talk. Hillary said, “We need to talk about sex and about being responsible. Are you sexually active?” Chelsea answered, “Not according to Dad.”

21. Perhaps the most telling criticism of her as wife and mother comes, not from the Internet, but from the Starr Report. Malti-Douglas analyzes the Starr Report’s frequent mention of the “absent” Mrs. Clinton:

Is the reader to surmise that Mrs. Clinton’s travels are what set the events in motion? The moral is clear: a wife should be by her husband’s side. In the sexual-moral world of The Starr Report, the liberated-woman First Lady has her share of responsibility in the affair. Thus it is that the narrator remarks that: "During the fall 1996 campaign, the President sometimes called from trips when Mrs. Clinton was not accompanying him. During at least seven of the 1996 calls, Ms. Lewinsky and the President had phone sex.” From Mrs. Clinton’s absence on the campaign trail, one progresses to phone calls to Lewinsky and from there to phone sex. (50-51).

22. First lady scholarship is a fascinating corner of history that questions malestream approaches to history centered on men’s public roles and policies. See, for example, Mayo and Meringolo; Caroli; and Gutin.

23. This web-site attributes Clinton’s presidency and policies to communist motives. The sexual social drama grafts nicely onto political ideology here, reflecting Laura Kipnis’ Marxist analysis of adultery: “Perhaps in the analogy of workplace protest we may find an idiom, like communism as theorized by Marx and Engels, through which to think about adultery as a form of social articulation, a way of organizing grievances about existing conditions into a collectively imagined form, and one which offers a vehicle for optimism about other, better possibilities” (294).

24. All of these philandering husband jokes were also told of Gary Hart (Dundes).

25. In her analysis of editorial cartoons published in newspapers depicting Hillary Rodman Clinton, Charlotte Templin explores a number of cartoons that picture the Clintons in bed: “Characteristically, the Clintons lie in bed back to back or side by side focused on documents, a book—something other than each other” (27).

26. Many Internet sites posted these three limericks as the “winners” in a contest that challenged writers to combine the names Monica Lewinsky and Ted Kaczinski, the Unibomber:

There once was a girl named Lewinsky

Who played on a flute like Stravinsky

‘Twas “Hail to the Chief”

On this flute made of beef

That stole the front page from Kaczinski.Said Bill Clinton to young Ms Lewinsky

We don’t want to leave clues like Kaczynski

Since you look such a mess

Use the hem of your dress

And wipe that stuff off your chinsky.Lewinsky and Clinton have shown

What Kaczynski must surely have known:

That an intern is better

Than a bomb in a letter

Given the choice of how to get blown.Works Cited

Ahluwalia, Rohini. “Examination of Psychological Processes Underlying Resistance to Persuasion.” Journal of Consumer Research 2 (2000): 217-32.

Anderson, Karrin Vasby. “From Spouses to Candidates: Hillary Rodham Clinton, Elizabeth Dole, and the Gendered Office of U.S. President.” Rhetoric and Public Affairs 5.1(2002): 105-132.

Bhattacharyya, Gargi. Sexuality and Society: An Introduction. London and New York: Routledge, 2002.

Berg, Leah H. Vande. “Living Room Pilgrimages: Television’s Cyclical Commemoration of the Assassination Anniversary.” Communication Monographs 62.1 (95): 47-65.

Bostdorff, Denise M. “Hillary Rodham Clinton and Elizabeth Dole as Running “Mates” in the 1996 Campaign: Parallels in the Constraints of First Ladies and Vice Presidents.” The 1996 President Campaign: A Communication Perspective. Ed. R. E. Denton, Jr. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998.

Bostdorff, Denise M. “Vice-Presidential Comedy and the Traditional Female Role: An Examination of the Rhetorical Characteristics of the Vice-Presidency.” Western Journal of Speech Communication 55 (1991): 1-27.

Califia, Pat. Public Sex: The Culture of Radical Sex, 2nd ed. San Francisco: Cleis, 2000.

Califia, Pat. Sex Changes: The Politics of Transgenderism. San Francisco: Cleis, 1997.

Caroli, Betty Boyd. First Ladies, expanded edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Connell, R. W. Masculinities. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1995.

Deem, Melissa. "Scandal, Heteronormative Culture, and the Disciplining of Feminism." Critical Studies in Mass Communication 16 (1999): 86-93.

Didion, Joan. Political Fictions. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001.

Doyle, James. The Male Experience. Dubuque, IA: W. C. Brown, 1983.

Dundes, Alan. “Six Inches from the Presidency: The Gary Hart Jokes as Public Opinion.” Western Folklore 48.1 (1989): 43-51.

Dyer, Richard. White. London and New York: Routledge, 1997.

Edelmen, Murray. Constructing the Political Spectacle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988.